A good place to start is to define what load management actually is. There is a whole host of contrasting opinions on what load management is and what it consists of. Training load is essentially the training that an individual is subject to. Whether it’s the distance or time ran, the weights lifted in the gym or laps swam in the pool.

It goes without saying that to improve performance across any domain, an adequate amount of training is required to further enhance an individual’s ability to perform. Yet, with any form of training comes with a risk of injury. Clearly, injuries across any form of sport are far from ideal, yet injuries that are caused by too much training, or an overload, are even more of a problem, as they can be prevented by paying more attention to an individual’s training load.

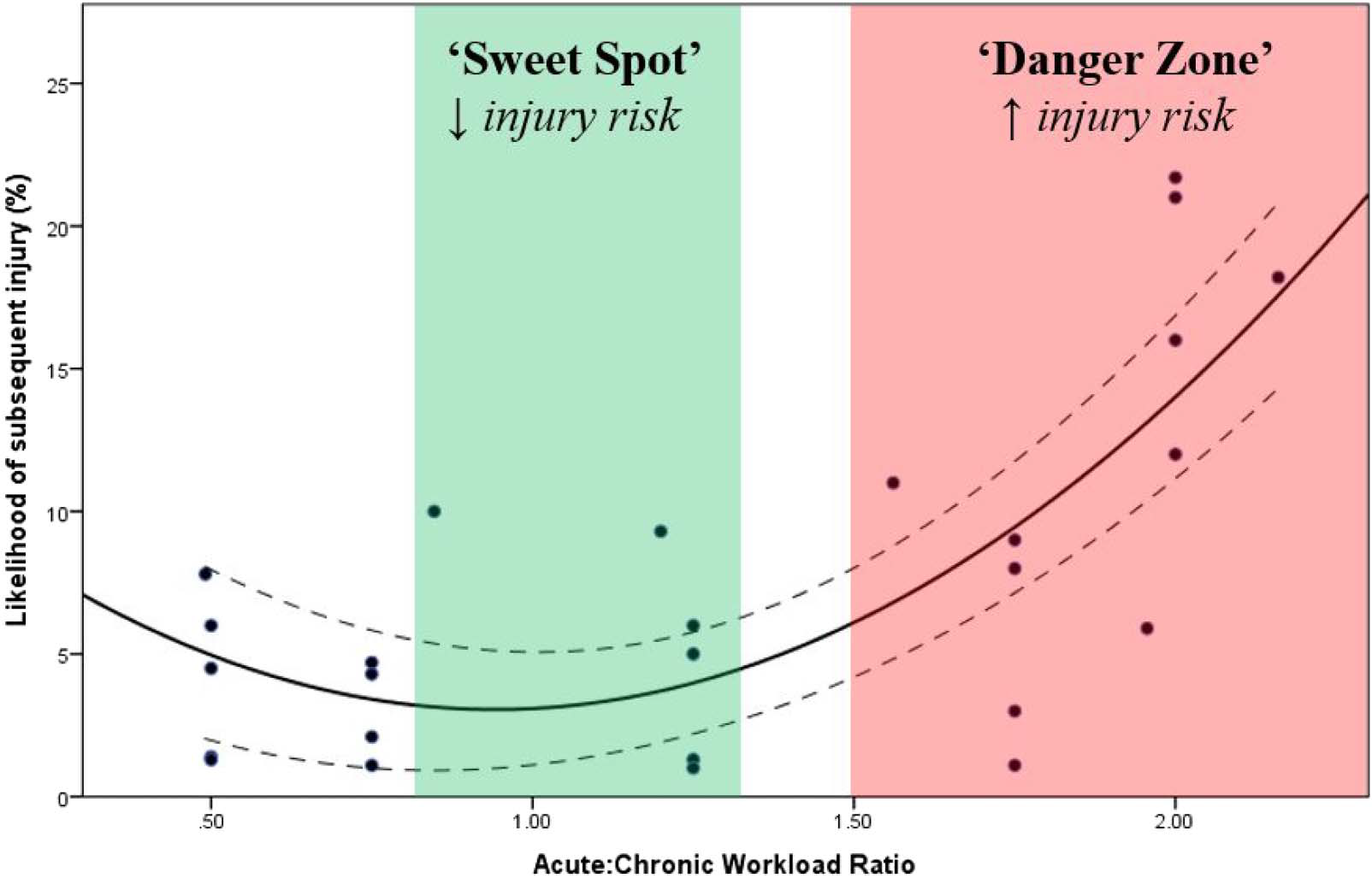

The coveted “sweet spot” of training prescription maximises performance potential by having an appropriate training load whilst at the same time, limiting the negative consequences of training, such as injury, illness or fatigue.

So how can you reach that sweet spot of training? A common method in elite sport across the world is by figuring out your acute and chronic workload ratio, which admittedly sounds like an arduous task, but is a lot simpler than you think.

- Acute training loads can be as short as one training session, but a weeks’ worth of training is a lot easier to interpret and much more logical.

- Chronic training loads represent the rolling average of the last 3-6 weeks of training.

So, just to bring that to life, let’s say you’ve done 3 runs of 30mins in a week, 90mins total volume, then this becomes your acute training load for that week. If you’ve managed to do that continuously for 3 weeks, then your chronic load becomes a total of 270mins, averaging out as 90mins per week. If after these 3 weeks of training, you feel ready to progress and run for a longer duration, then this is where the acute:chronic ratio can be helpful.

Academic research looking into this acute:chronic ratio has come up with an effective way of applying it to increasing training volume, or, running more. Essentially, the most efficient way of progressing your training is not to increase your acute training load (in this example, total running time of 90mins across the week) over 30% of this amount in the following week, which would equate to 120mins total running volume, or even a progression to 40min runs from 30mins. This method allows for that progression and really facilitates your ability to do that, whilst minimising the risk of injury at the same time. So why 30%? Again, referring back to the research, currently it shows that anything above this 30% increase enters the danger zone for injury risk, which is demonstrated nicely in this graph below:

As with most things, there is an element of common sense to running more and getting injured less. Allowing your body to adapt to what you’re doing does take time and rushing through this process can result in it becoming a little more problematic. Gradual exposure to anything over time often results in greater outcomes in the world of sports performance, and running is no different.