Equality, diversity and inclusion

by Dr Carol Bolton

In April 1792, a group of 275 men, women, and children left England in three ships bound for the west coast of Africa. Their plan was to buy an island there and colonise it to demonstrate that Africans and Britons could work together for the benefit of both nations, and it was propelled by well-meaning anti-slavery sentiment at a time before the British slave trade was ended (1807). So instead of capturing and forcibly transporting Africans to the West Indies as slaves, they proposed a more humane economic model of employing them in their own continent. Because the tropical climate of Africa favoured growth of the products that the slave trade relied on (such as sugar cane, cotton, and indigo) they planned to farm the land and pay the workers for their labour, thereby engaging with them in a mutually beneficial way. The other, broader intention shared by the colonists (misguided as this may seem to modern observers) was to educate and ‘civilise’ Africans by bringing British social structures, cultural standards, and Christian religion to them.

We know the details of this enterprise today, mostly through a book that was written about it and published in 1805 called African Memoranda. This was written by Captain Philip Beaver, who was a naval officer on half-pay at the time, due to a peace-time period before the French Revolutionary Wars began in 1793. He was persuaded to join the colonists because he shared their anti-slavery principles, and at this time he was a young man seeking adventures abroad.

Beaver’s journal of the time the colonists spent on the island of Bolama (which they actually purchased twice because they were not aware of who owned it) is a fascinating narrative. He describes their voyage and arrival, their attempts to set up the colony, the attacks on them by Africans who inhabited the region and were suspicious of their motives, the frequent outbreaks of disease (yellow fever was endemic on Bolama), and the sad catalogue of recurrent deaths. When the original governor of the colony returned to Britain two months after their arrival, it was Beaver who took control of the settlement and according to him, was largely responsible for it surviving as long as it did.

However, the colonial experiment failed in the end, with all the settlers dying or returning to Britain. By November 1793, Beaver and one other remaining colonist had also decided to return home. Nevertheless, Beaver’s book, which was published thirteen years after their attempt to create the colony, contains an extensive justification of their actions. This was because despite their settlement failing, he believed that the experiment had succeeded in its abolitionist goal. They had used African labour to cultivate the island and Beaver was convinced that Bolama was still a viable colonial objective, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps.

My interest in the colony and the people who took part in it, was the reason for publishing an edition of Beaver’s book with Anthem press (due to appear in June 2022). This new edition will provide additional information about the lives of the settlers and the African people they lived among during their time there. I believe there is a need for this contextual material because, while Beaver’s narrative is interesting in its own right as a first-person account of the colony, it dominates our perceptions of what happened on the island and occludes other lives and voices. For instance, the motivations of the colonists were varied. Some had strong abolitionist principles or had nationalist ambitions to expand British territories abroad; others were faced with forcible transportation rather than serve a prison sentence or saw a new life abroad as a way out of poverty. In bringing this edition to modern readers I will be finding out about the people who were affected by this venture and uncover their individual histories – as far as this is possible over two centuries later. These people have become largely invisible to us, not just because of the time-distance from them, but because of their positions within a class-based, patriarchal society that was less inclusive of diversity. In this way the project dovetails with my other research as a literary historian, which focuses on illuminating lesser-known writers and aspects of history from the British Romantic period. I am particularly interested in narratives of travel, exploration, and colonisation, because I believe that these accounts give us insight into other lives and experiences that are not always evident in more canonical forms of literature, and I envisage Beaver’s book adding to this very important historical corpus.

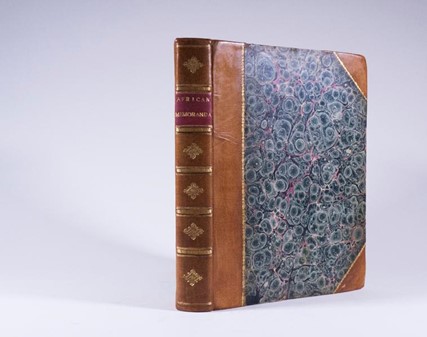

![‘Plan of the Island of Bulama’ from C. B. Wadstrom’s Essay on Colonization (1794). [Photograph by Carol Bolton, reproduced by permission of Cambridge University Library]](/media/media/schoolanddepartments/schoolofsocialsciences/images/edi-blog-3.jpg)

[Photograph by Carol Bolton, reproduced by permission of Cambridge University Library]