Marking the 25th anniversary of The Women’s Prize, under the bold tagline of “finally giving female writers the credit they deserve”, 25 novels have been reprinted using the real names of 26 writers who used male pseudonyms.

The scheme may have some positive outcomes, such as introducing readers to writers and works they might not have otherwise discovered. However, whether it gives female writers the credit they deserve is up for debate.

Mary Ann, Marian and George

The collection’s lead title, touted in all press coverage of its release, is George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1872) – now published with the author’s name given as Mary Ann Evans. Though this was the name given to her at birth, Eliot’s “real name”, or the name by which we should refer to her, has been a matter of debate by researchers for years.

She experimented with alternative spellings like Marian and with completely different names like Polly, used her common-law husband’s surname, Lewes, for much of her literary career, and was known as Mrs Cross at the time of her death. 19th-century readers would have known exactly who to assign credit to. Her true identity was revealed shortly after the publication of her second novel, Adam Bede (1859), and at the height of her literary fame she signed correspondence ME Lewes (Marian Evans Lewes).

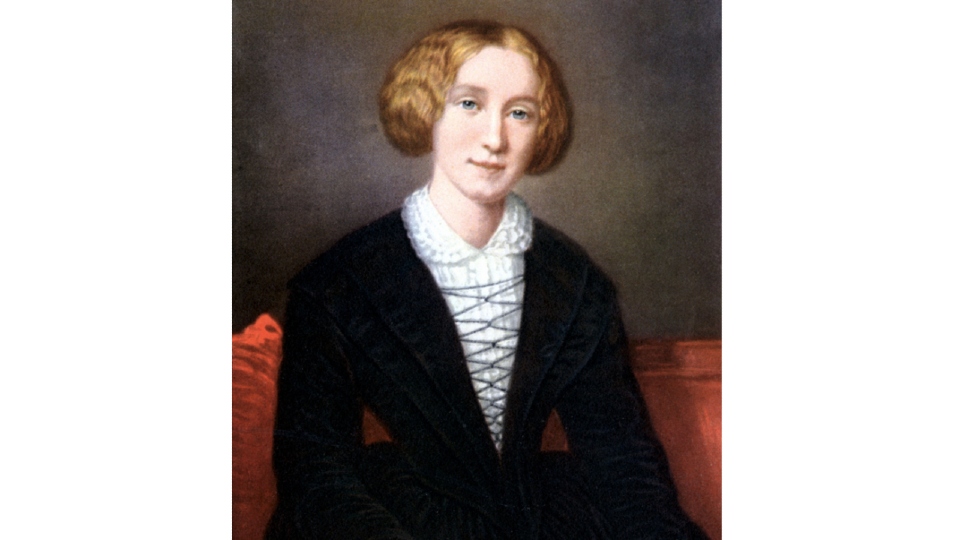

George Eliot portrait. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

George Eliot portrait. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

Eliot’s own consideration of the name she should be known by is as complicated a psychological and moral question as any depicted in her novels. However, her wish to be known professionally as George Eliot is resolute and clearly articulated. It helped her separate her personal and professional personas. Choosing a name to publish under is an important expression of agency and using a different name without the author’s input and consent deprives them of that agency rather than reclaiming it.

It is also important to debunk a common misconception to understand why this campaign is misguided. In George Eliot’s time, women did not have to assume male pseudonyms to be published. Writers who opted to use pen names tended to choose ones that aligned with their own genders. In fact, in the 1860s and 70s men were more likely to use female pseudonyms than vice versa. William Clark Russell, for example, published several novels under the name Eliza Rhyl Davies.

Women dominated the literary marketplace as both readers and writers for the majority of the 19th century. Of the 15 most prolific authors of the period 11 were women, according to the At the Circulating Library.

The need to project modern gender imbalances that exist in publishing today onto 19th-century authors is understandable but anachronistic...

Eleanor Dumbill, a Doctoral Researcher at Loughborough University, discusses why it’s not empowering to abandon the male pseudonyms used by female writers in the Conversation. Read the full article here.