Devon Tyso, a Product Design and Technology student, has designed ‘PRO check’, an innovative tool designed to replace the traditional digital rectal examination (DRE), which involves a doctor manually assessing the prostate with a finger.

According to Devon, the current approach is heavily reliant on a clinician’s subjective judgement and experience, and many see the method as ‘intrusive’.

“As one in seven men will get prostate cancer, it’s vital to detect abnormalities early and track changes over time,” said Devon, “The current examination method involves a lot of guesswork.

“PRO check provides objective, measurable data and allows prostate health to be visualised – enabling more accurate diagnosis, and improved long-term monitoring.

“Having a device conduct the exam may also feel less invasive, which may encourage more men to get checked, potentially catching issues earlier.”

How the device works

Designed for use by GPs during routine prostate assessments, PRO check allows doctors to evaluate the size and texture of the prostate — two key indicators of potential health issues — in a more objective and consistent way than the traditional digital rectal examination.

The device is a handheld probe, and it is covered with a condom before being inserted into the body. Once in position, the condom inflates to different pressures, pressing against the surface of the prostate, causing it to compress. A laser grid is projected onto the inner surface of the condom so the shape of the underlying prostate can be captured.

Stereoscopic cameras capture images of the laser grid, tracking where the gridlines intersect and how these intersections shift as pressure changes. This information is then fed into mathematical equations to create 3D images — or ‘topographical representations’ — that reveal the prostate’s shape and surface structure under different pressures.

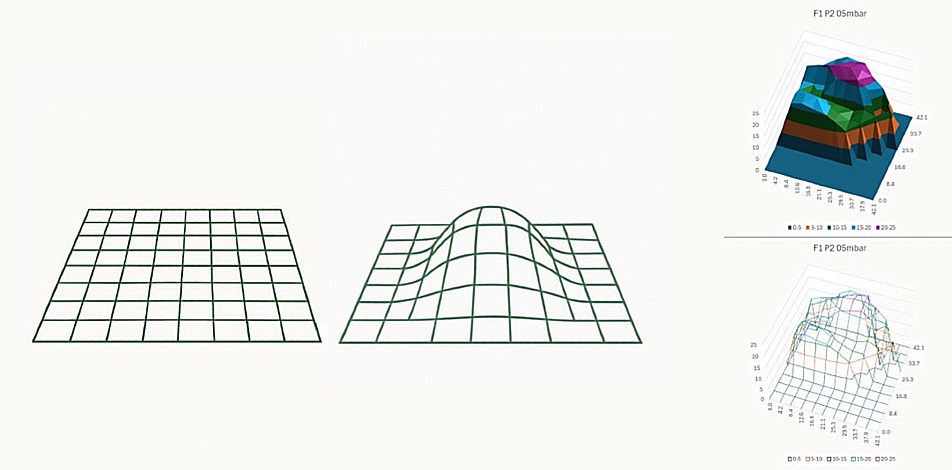

A flat grid (left) and a deformed grid (right) illustrate how laser gridlines projected onto the condom surface shift as pressure is applied against the prostate. By tracking changes in the intersections of the gridlines, mathematical equations can reconstruct 3D images - shown on the far right – that reveal the prostate’s shape and surface structure under varying pressures. Please note: this is a conceptual diagram and not a technically accurate representation of how the lasers or imaging system work.

A flat grid (left) and a deformed grid (right) illustrate how laser gridlines projected onto the condom surface shift as pressure is applied against the prostate. By tracking changes in the intersections of the gridlines, mathematical equations can reconstruct 3D images - shown on the far right – that reveal the prostate’s shape and surface structure under varying pressures. Please note: this is a conceptual diagram and not a technically accurate representation of how the lasers or imaging system work.

Studying the prostate’s surface details could help clinicians identify areas requiring further investigation. Healthy prostate tissue is typically soft and compressible, so regions that appear stiff or resist pressure could indicate potential abnormalities and warrant further investigation.

The device can also produce data on prostate volume – one of the measurements used to calculate prostate-specific antigen (PSA) density, which helps assess prostate cancer risk. Devon says currently volume estimates are often based on a clinician’s best judgement.

In addition, data from PRO check can be used to generate a compressibility-versus-pressure graph – a novel data type not currently available in clinical practice. This graph shows how the prostate compresses at different pressure levels, which Devon hopes could offer new insights into prostate health and complement existing diagnostic tools.

PRO check is designed to integrate with artificial intelligence, enabling automatic extraction of video data, real-time calculations, and the generation of 3D images for live display on a laptop or tablet during the examination.

The idea is that all examination data from PRO check would be stored on the patient’s records, helping to build a personalised prostate health profile that can be tracked and monitored over time.

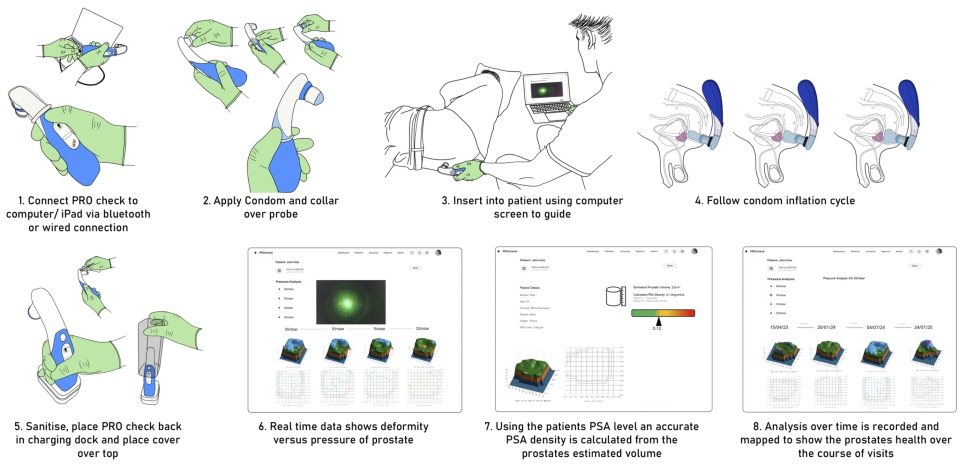

A storyboard showing how PRO check could be used by medical professionals to record and monitor prostate health.

Inspiration

Devon’s inspiration for PRO check came from a mix of personal experience – after his grandfather’s prostate cancer diagnosis – and unexpected technical research.

“It really hit home how common prostate issues are after my family member was found to have an enlarged prostate,” said the 22-year-old from Cardiff, “I realised nearly everyone I spoke to about it knew someone affected by it.

“When I started looking into prostate examinations, I kept thinking ‘how can a doctor remember what your prostate felt like four months ago?’ and how horrible it must be just be told whether you’re fine or not without seeing any data or anything visual.”

While researching non-invasive ways to assess tissue structure inside the body, Devon came across a technique used by NASA to map the surface of asteroids — projecting laser grids onto them, capturing images with satellite-mounted cameras, and analysing the gridline intersections to reveal the contours of the surface.

“I saw that NASA were mapping surface heights on a massive scale, and I thought – if they can do that in space, why can’t we use similar principles to examine something here on Earth?” said Devon, “I’ve basically used the exact same technique and scaled it down for PRO check.”

Prototypes

Devon designed PRO check as part of his final year project – which was exhibited at the School of Design and Creative Arts’ 2025 Degree Show – and has prototyped several of its key components.

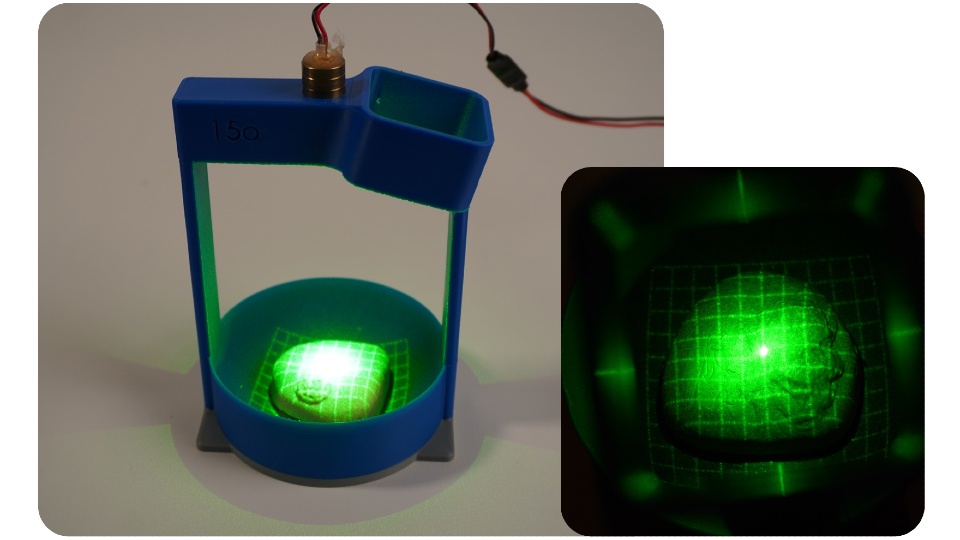

He has built and tested two working prototypes. The first demonstrates how a laser grid and camera can be setup to map the surface of the prostate.

Devon designed a custom rig that enabled him to capture images of a laser grid projected onto different silicone prostate models — representing a healthy gland, a small tumour, a large tumour, and an enlarged prostate — from an optimal angle using a smartphone camera.

PRO check prototype one demonstrated how laser gridlines and a camera can be used to image the surface of the prostate.

PRO check prototype one demonstrated how laser gridlines and a camera can be used to image the surface of the prostate.

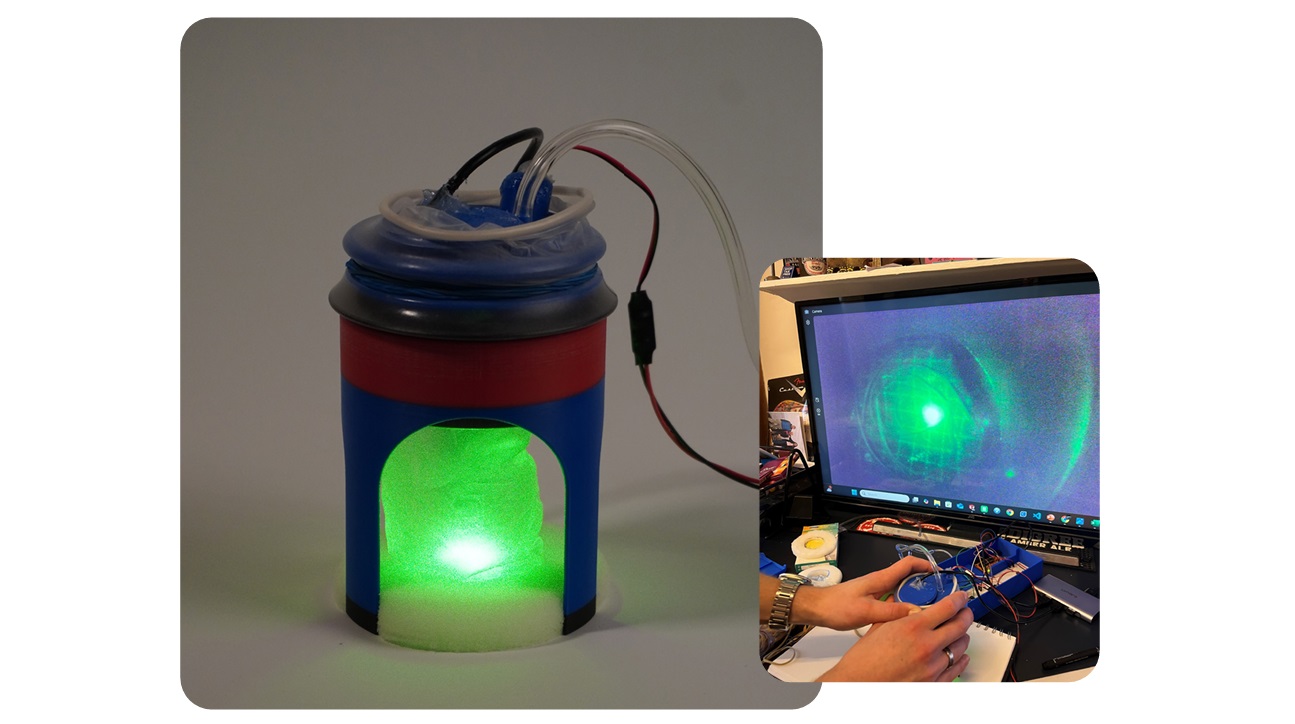

The second prototype features electronics that inflate a small balloon at controlled pressures, regulated by a pressure-sensing chip. Devon consulted three healthcare professionals to measure the pressure typically applied during prostate exams and replicated those levels in his design.

Devon tested the prototype using the silicone prostate models but encased them in a sponge disc to simulate surrounding tissue. PRO check prototype two demonstrates how a balloon can be inflated to set pressures against prostate models with surrounding tissue simulated using sponge.

PRO check prototype two demonstrates how a balloon can be inflated to set pressures against prostate models with surrounding tissue simulated using sponge.

Devon manually extracted data on the gridline intersections from the camera footage and applied mathematical equations to generate 3D images of the prostate surfaces and surrounding tissue under different pressures.

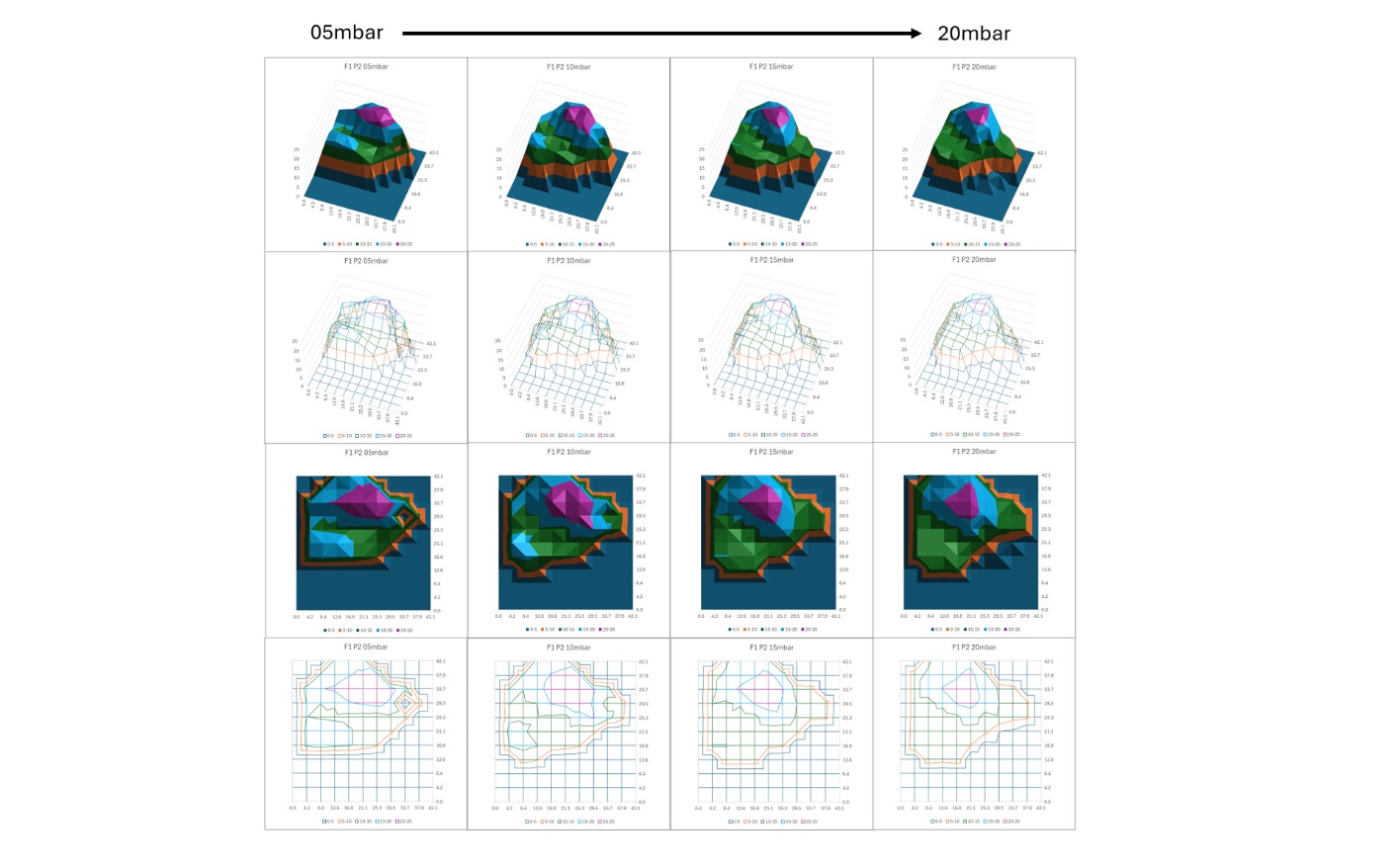

Data captured and analysed from the PRO check prototype shows how a model prostate and surrounding tissue compress under increasing pressure (from 05 mbar to 20 mbar, in 5 mbar increments). The top two rows display 3D surface maps and wireframe representations of tissue deformation, while the bottom two rows show 2D contour plots. Areas that remain elevated or flatten under pressure help visualise changes in prostate shape and stiffness across different pressure levels.

Data captured and analysed from the PRO check prototype shows how a model prostate and surrounding tissue compress under increasing pressure (from 05 mbar to 20 mbar, in 5 mbar increments). The top two rows display 3D surface maps and wireframe representations of tissue deformation, while the bottom two rows show 2D contour plots. Areas that remain elevated or flatten under pressure help visualise changes in prostate shape and stiffness across different pressure levels.

Next steps

Devon will be exhibiting PRO check at New Designers – an annual London showcase of the UK’s most innovative emerging design talent – this July.

He hopes to collaborate with medical professionals and product developers to turn PRO check into a fully realised medical device.

When speaking about his ultimate goal, Devon said: “I’d love to see this used in GP surgeries across the UK one day.

“With early detection being so critical, anything that helps men get checked sooner and more comfortably – and provides reliable data and visualisations – has huge potential. I really believe this could make a difference.”

Further information on PRO check can be found on the Degree Show website. Those interested in collaborating with Devon can email devon.lewis.tyso@gmail.com.