GaWC Research Bulletin 165 |

|

|

|

This Research Bulletin has been published in Belgeo, (3), (2005), 265-273. Please refer to the published version when quoting the paper.

INTRODUCTIONI will use a recent news story to introduce this lecture. Last week the media reported a story with headlines such as: “Detroit to cut 10,000 jobs in Europe”. What does this mean? Apart from the peculiar geography - it’s not a city but a firm (General Motors) that has made the decision, and it’s not a ‘continent’ that is affected but car plants mainly in cities in one country (Germany) – there are two important features: first, the process is transnational, and second, it is economic. In other words, it is an archetypal event that has come to be called “globalization”, featuring a major corporation in one country directly affecting the economy of another country. This lecture is about globalization and its study, as interpreted by a world-systems analyst (i.e. me). The ideas associated with globalization and world-systems analysis are sometimes viewed as comparable and other times they are contrasted. Clearly I need to engage in some careful definitional work before providing a new interpretation of how world-systems analysis can inform our understanding of contemporary globalization. Thus I begin with definition exercises for first, world-systems analysis, and second, contemporary globalization. The new understanding is then presented as an adaption of Jane Jacobs’ classic work on the city to Saskia Sassen’s more recent classic work on the global city. WORLD-SYSTEMS ANALYSISWorld-systems analysis is an approach to understanding social change based upon geohistorical systems. These provide a space-time framework for understanding social change that replaces the orthodox use of nation-state as the basic unit of change (i.e. space as ‘homeland territory’ and time as ‘rise of the nation’). Geohistorical systems denote specific structures of social relations that are concretely realized through time (trends and cycles) and space (extent and order). The modern world-system is a capitalist world-economy which is the geohistorical system in which we live. The basic geohistory is that it was constructed in Europe in the ‘long’ 16th century, it expanded to cover the whole world by c.1900 (i.e destroying all other systems), and will meet its demise in the 21st century. Looking at social change in this way we find that the basic motor of the system is ceaseless capitalist accumulation. This dominant process of social change generates specific times and spaces.

Although separated for pedagogic reasons, these two structures are intimately entwined to produce the social space-time structure that is the modern geohistorical system. This approach to social science was pioneered by Immanuel Wallerstein in the 1970s. The first question you should always ask of new knowledge initiatives is about their own space-time context. What were the key geohistorical challenges that world-systems analysis was designed to overcome? Drawing on his ‘first world’ experience of the 1968 revolutions that spurned the orthodox ‘old’ left, and his ‘third world’ experience of severe constraints on national liberation revolutions, Wallerstein directly challenged the two great geographical myths of the times:

For Wallerstein, both development and ‘economic systems’ are properties of the whole historical systems, NOT individual counties. World-systems analysis was devised to counter these myths. How does this approach interpret the world today? The early twenty first century is a very unusual, exciting and unstable time for the two very different reasons:

GLOBALIZATIONGlobalization comprises a bundle of processes that originated in the 1970s with: 1. the rise of multinational corporations culminating in ‘global reach’ (a popular book of that name appeared in 1973) producing a new international division of labour; and 2. the collapse of Bretton Woods fixed currency arrangements in 1971 culminating in a new worldwide financial markets (transcending national control); both based upon 3. computing/communication enabling technology that made such worldwide organization possible. The concept of globalization has been applied to all spheres of social activity - global civil society, global governance, global culture, and global economy – but it has been the latter that has dominated the discourse. This is because globalization has been closely associated with the rise of neo-liberalism, the dismantling of state mechanisms of economic protection and redistribution built up throughout the twentieth century. With its privileging of market processes, proponents of globalization favour, indeed famously proclaim, a borderless world. The discourse of globalization is largely a product of the 1990s. There were three key political challenges that globalization proponents were trying to overcome. This politics was about making all the world attractive to capital:

Generally, this involved the privatization of state assets, and ‘opening’ state economies to foreign investment and trade. The end-result was to move from ‘three worlds’ to ‘one world’ = GLOBALIZATION. Globalization is truly a keyword of our times, overwhelming all other conceptions of macro-social change in the 1990s. Today it is a hugely contested concept both empirically and politically. My position is as follows:

These positions are basic world-systems interpretations. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WORLD-SYSTEMS ANALYSIS & GLOBALIZATIONHow do the two discourses on social change relate to one another? Put simply: globalization proponents treat world-systems analysts as “pioneers” of global study but reject their systems framework; while world systems analysts consider globalization proponents as “Johnny-come-latelys” and reject their faith in the ‘market’. Of course, both rejections are very fundamental. In some ways it is hard to imagine two approaches to understanding contemporary social change that could be more different. To begin with, they have wholly contrasting pedigrees, one being a coherent, scholarly block of social science knowledge, and the other being a motley collection of writings, dominated by business gurus. This is reflected in their respective politics: neo-Marxist versus neo-liberal and latterly neo-conservative. Nevertheless, I will argue that instructive comparisons can be made in terms of their similarities. I identify three key similarities:

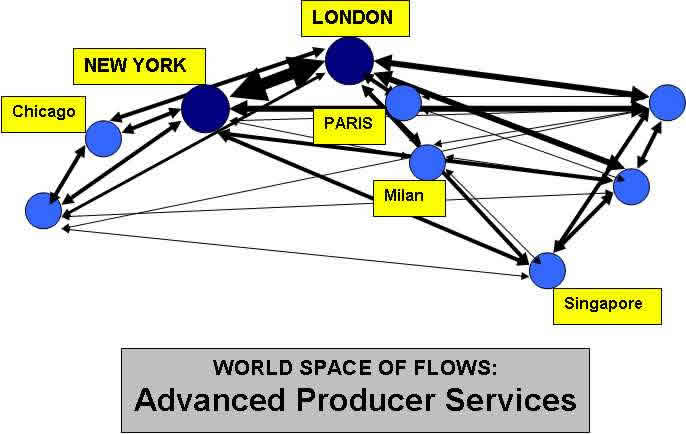

I am going to develop an argument covering all three points but starting in reverse order: can cities have a future as the organizational nexus of a global economy cum global civil society cum global governance cum global culture? JACOBSEAN SOCIAL SCIENCEThe social science I am trying to develop takes its name from Jane Jacobs, author of some pathbreaking books on economics and the city. Like the two approaches previously described, she similarly rejects the state as a fundamental unit of social analysis. Her concern has been what she calls the “myth of the national economy” – she asks why should politically defined state-spaces delimit economies. However, in this criticism of state-centric thinking we are provided with a concrete, analytical alternative: cities and city-regions. Thus she identifies ‘national economies’ (sic) as politically-defined “mish-mash amalgams of city economies”. For Jacobs, dynamic cities are the starting point for understanding economic life and how it grows. My admiration for Jacobs stems back to her 1984 prediction of the economic demise of Japanese cities because of their shouldering the burden of the Japanese state (rural-based political parties squandering urban-generated wealth). Nobody else saw the end of Japan’s ”economic miracle“ while it was still in full swing. In the 1990s when she was proven correct, I began a personal re-evaluation of her work on cities which has culminated in my researches on the world city network. Her basic argument is that cities (not states) are the fundamental units of economic life and that the latter is made vibrant and dynamic through economic interactions within and between cities. Thus economic growth is equated with dynamic cities, not state development. I equate Jacobs’ dynamic cities (wherein new work is created, new production replacing imports that creates a more complex city economy) with Saskia Sassen’s global cities (wherein massive quantities of new work has been created in professional and financial services, referred to in the literature as advanced producer services). Given that the latter work is global in scope, I focus on cities as networks, and the agents of network formation – professional and financial service firms with their worldwide office networks (prime contemporary creators of new city work). Thus I treat globalization as structured through contemporary dynamic cities (global service centres) that form a world city network. This specific conceptualisation of a contemporary world city network has proven to have much potential for empirical analyses. By focussing on the network-making agents that interlock cities (such as banks) data has been assembled that can be modelled to provide estimates of particular flows between cities. This relies on the simple idea that the larger a firm’s office, the more flows (information, instruction, plans, strategy, advise, etc) to other offices it will generate. Thus through collecting information on many offices within a city, indirect measures of that city’s links to other cities can be computed. Following Sassen, this method, using the interlocking network model, was initially applied to advanced producer service firms but application has subsequently been broadened to other, sometimes non-economic, agents of network formation. For instance, NGOs operate through cities across the world and thus contribute to their interlocking as a world city network. In the remainder of this lecture I present examples from my world city network research to show new geographies of globalization, global spaces of flows through cities superseding the international spaces of places that are states. Because only a limited number of flows can be shown clearly on static diagrams, my illustration shows only the upper echelons of the world city network. Figure 1 shows the leading world cities (most connected) and their inter-city relations as defined by the office networks of advanced producer service work (in accountancy, advertising, banking/finance, insurance, law, and management consultancy). Note that the nine cities break evenly across the three main globalization arenas, the USA, western Europe and Pacific Asia. However, within this arrangement, two cities stand out above the rest: London – New York is “Main Street, World-Economy”. The next two figures show how this global space of flows is organized using world-systems categories. Figure 2 shows the cities wherein the headquarters of advanced producer service firms are concentrated. Not as evenly spread as in Figure 1, the eleven headquarter cities – service control centres – split six in western Europe, four in the US and just one, Tokyo, in Pacific Asia. This is a map of command power, the loci of service corporate decisions and from whence consequent instructions flow out across the world. This is the ultimate core process in the world city network and Figure 2 is therefore a depiction of the core of the world-economy as defined by command power, highest-level work in the world city network. But there is another category of power that is intrinsic to all networks, and is clearly manifest in the world city network. Networks are premised upon collaboration, without a degree of synergy between the elements, networks disintegrate. Thus, for cities to form a network, there must be mutuality between them – city networks have to encompass co-operative mechanisms to operate. Therefore all cities in a network have a basic network power, it is the reason they form part of the network. Like other power categories, network power varies among its holders. Take Hong Kong as an example. It appears in Figure 1 but not Figure 2 but this does not make it an unimportant world city. It may have no headquarters of global service corporations but it is a place where all serious global service players have to be. Hence Hong Kong has immense network power as the place-to-be for linking the booming Chinese economy to the rest of the world. It is where knowledges about Chinese opportunities criss-cross professional knowledges that convert opportunities into practice. Such cities are traditionally called gateways and I keep this terminology in Figure 3 which depicts the 24 leading gateway cities in the world city network, as defined by numbers of links for non-command cities. Most are national gateways (Buenos Aires, Toronto, etc.) but seven are multinational including Miami and Zurich as centres for servicing regions of the erstwhile ‘third world’ from a ‘first world’ base. Figure 3 can be interpreted as depicting world-systems spatial categories in the contemporary global space of flows. The three zones of command power represent the core, the gateways represent the semi-periphery (part service core, part mega-city peripheral processes), and the rest, the background of the map is the periphery (by definition a place with no dynamic cities). What I have described is a global space of flows organized through command world cities, and regional, and national “gateway” cities that are reproducing the world-systems core-periphery structure CONCLUDING COMMENTI will conclude with another news story dominating the media at the moment: who will win the US Presidential Election? My purpose is not prediction but to show how the ideas developed here can be applied to something as inherently ‘statist’ as a national election. The two approaches I described have fairly clear-cut positions on this topic. For globalization proponents, post-World War II Americanization was the precursor of globalization, and the USA remains the ‘privileged’ power: Bush is exploiting this situation and moving the US from a neo-liberal to a neo-conservative trajectory. In world-systems analysis, the USA is in hegemonic decline as it uses political-military power to compensate for declining economic power: just as the growth of the British Empire occurred after British economic dominance in the industrial revolution, so we should expect historical figures like Bush to appear, using up American wealth with great political bravado. However both these arguments treat the USA as an undifferentiated geographical unit – I think a good dose of Jacobsean social science is needed to rectify this. Current interpretations of US aggression tend to emphasize the frontier myth of US society, the idea that the nineteenth century ‘heroic winning if the west’ has imprinted expansionary tendencies in the country’s collective psyche. However, I think a rather different geohistorical idea is much more useful for understanding contemporary US military adventures – sectionalism. In this context ‘section’ means region, specifically the US division between North and South. US history can be framed through its North-South divide: 1. Sectional compromise from Constitution to Civil War Figure 4 is a schematic diagram dividing the USA along North-South lines (including a division of California) showing the different roles of the sections. The North is a world of makers and traders. Northern cities were the builders of US hegemony: after the Civil War they made the US the dominant economic power in the world culminating in its immense pre-eminence in the mid-twentieth century. In contrast the South is a world of soldiers and circuses. The South got rehabilitated into the US mainstream through its military tradition that was found to be so useful in the twentieth century’s two world wars. Along side the numerous army and navy bases we find the playground of America in music (New Orleans jazz, Memphis blues, Nashville country), films (Hollywood) and vacations (Disneyland, Disneyworld, Las Vegas). Wealth historically created in the North is squandered in the South, both domestically (play) and internationally (war and military bases). The key point is that since the 1960s the South has finally “won the Civil War” which translates internationally to building a US empire, which is a good shorthand for Bush’s interventionist, unilateralist, foreign policy. How does this relate to the upcoming election? “Winning the Civil War” in contemporary times means winning elections. John F Kennedy in 1960 was the last politician from the North to win the presidency. (There is another President from the North, Gerald Ford of Michigan, but he only became President when Nixon resigned; in the next election he lost to the Southerner Carter.) The lesson is: Southerners beat Northerners whatever the party labels. Bush is from Texas, Kerry is from Massachusetts, ‘nuff said.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTEBy its nature, a public lecture does not have a list of references but readers less familiar with the subject matter may find a brief introduction to some key references useful. The basic references on world-systems analysis are by Immanuel Wallerstein: WALLERSTEIN, I. (1979) The Capitalist World-Economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge WALLERSTEIN, I. (1983) Historical Capitalism. Verso, London WALLERSTEIN, I. (2004) World-Systems Analysis: an Introduction. Duke University Press, Durham, NC. The key references on the initial globalization trends of the 1970s are: BARNETT, R. J., Muller, R. E. (1974) Global Reach: the Power of Multinational Corporations. Simon and Schuster, New York FROBEL, F., HEINRICHS, J., KREYE, O. (1979) The New International Division of Labor. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. The most influential 'business guro' reference is: OHMAE, K. (1990) The Borderless World. Fontana, London. The starting point for understanding globalization is: LECHNER, F. J., BOLI, J. (eds) (2000) The Globalization Reader. Blackwell, Oxford. For the geographies of globalization, key texts are: DICKEN, P. (2003) Global Shift. Paul Chapman, London. JOHNSTON, R. J., TAYLOR, P. J., WATTS, M.J. (eds) (2001) Geographies of Global Change. Blackwell, Oxford. There are three key books by Jane Jacobs: JACOBS, J. (1970) The Economy of Cities. Vintage, New York. JACOBS, J. (1984) Cities and the Wealth of Cities. Vintage, New York. JACOBS, J. (2000) The Nature of Economies. Vintage, New York. The key text by Saskia Sassen is: SASSEN, S (2001) The Global City. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. The empirical section at the end of the talk derives from my recent book: TAYLOR. P.J. (2004) The World City Network: a Global Urban Analysis. Routledge, London Finally to keep abreast of the latter, reference should be made to the Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) web-site: "www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc"

NOTE*The Immanuel Wallerstein Chair Annual Lecture delivered by Peter J Taylor at the University of Ghent on October 21st, 2004 Figure 1:Global Space of Flows: Advanced Producer Services

Figure 2: Service Control Centres Figure 3: Gateways: National and Regional Figure 4: USA: North Makers versus South Takers Edited and posted on the web on 26th May 2005 Note: This Research Bulletin has been published in Belgeo, (3), (2005), 265-273. |

||