GaWC Research Bulletin 161 |

|

|

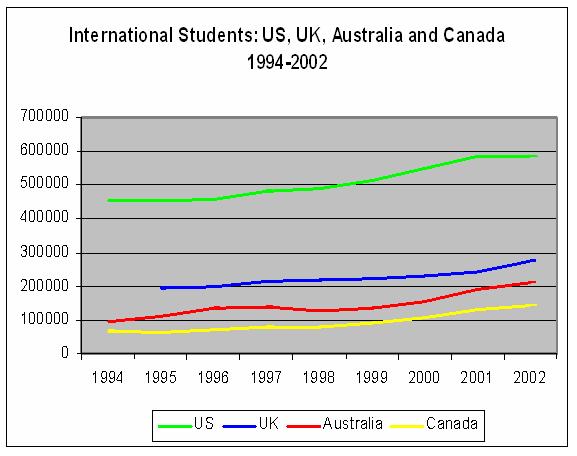

INTRODUCTIONGlobal economic, social and cultural forces change the vitality and internal structure of cities in a variety of ways. An understanding of those forces has emerged from an energetic research focus on the fortunes of global cities. That effort has been refined and adapted as researchers have struggled with the term global city and ways that it can be applied in practice and represented in information. One important step here was to look beyond the simple idea that global cities could be identified by listing their attributes (be they size, number of banks or number of headquarters) and pay attention to the linkages between them, identifying the cities with the most linkages as the cities with the highest status (Beaverstock et al 1999). These approaches have refined the earlier efforts to identify a global hierarchy of cities. The new perspective was however limited as the sole raw material in the researcher’s hands was measures of commercial service activity (summarized in an overview by Taylor 2004) or the branch networks of multi-national corporations (Alderson and Beckfield 2002) so but at their core these approaches still produce a narrowly-cast perspective of global activity. That narrow cast reflects the heritage of global city research in the work of Friedmann (1986) where power. dominance and control were critical dimensions in understanding the role and influence of cities. Although the insight produced by these approaches is substantial, there is scope to look at the way global links and global cities are connected in other ways. THINKING DIFFERENTLY ABOUT GLOBAL LINKAGES AND GLOBAL CITIESThe current paper extends an early argument (O’Connor 2002) for global city research to look at a broader array of global economic forces than has been targeted up to that time. That initial call was made in part to open up understanding of the economic opportunities in cities that appear in lower levels of the global hierarchy produced by the research cited above. It was argued many opportunities could emerge from global connections apart from those associated with commercial services. In turn these activities could have some previously un-considered spatial impacts. Most global city research emphasizes the development of the CBDs which are shaped by the “myriad flows between the office blocks that typify world city skylines” (Taylor 2003: 5). However there is now broader recognition of a spatial form originally labeled extended metropolitan areas ( McGee 1994) and recently labeled global city regions (Scott 2001). As articulated by Hall (2001) and Hack (2000) these spatial units incorporate suburbs and nearby cities surrounding the CBDs of global cities. The activity in these locations could include some of the broader array of global economic forces inferred above. The research reported here explores one of these different global functions and identifies their city and intra-city locations. In simple terms the aim is to explore the way that global trade (rather than just global producer services) shapes a global city hierarchy and is reflected in the internal patterns of city development. That might appear an overwhelming task, but it is simplified by some ideas of Storper (2000) who has divided trade into a number of categories, and in particular drawn attention to the importance of trade as exchange of similar products between advanced economies. One special component of that trade is the buying and selling of services, a growing part of world trade as shown by O’Connor and Daniels (2001). They found that service trade was strongest where service sector development was already advanced as firms within those nations exchanged similar services with one another. In turn they suggested that participation in this exchange depended upon the capacity of cities within each country. It is possible that some of these services could be supplied from places outside the well-developed list of global cities, as Kratke and Taylor (2003) showed for media cities and Townsend (2001) found for IT and the internet in the US. It is likely that cities involved in trade in other services such as design or transportation might provide yet another sub-set and a different geography, although the common quadrella of London, Paris, New York and Tokyo would probably figure in their geography.. In that spirit this paper reports on trade in tertiary education, a growing sector in many countries. EDUCATION AS A SERVICE EXPORTThe globalization of education has attracted considerable attention in recent years. This attention has come in part from a recognition of the value attached to international connections in student learning and as a source of innovation and stimulation for curriculum development ( Knight 1997). These perspectives have been expressed in national policy to encourage students to study abroad or to attract students from overseas (Callan 2000). Those values are enshrined in major programs to facilitate the mobility of students around the European Union. A second perspective on the globalization of education has emerged from thinking on the knowledge economy emanating from the ideas of Reich (1992). The symbolic analysts in the latter research perspective are believed to shape the performance of national economies through their problem solving, learning and skill development. That perspective (consistent with the earlier ideas of Romer 1990) call forth advanced education as a central need in national economic development. Participants in that advanced education will include among their number international students who move from their domestic education system to other nations in search of new perspectives and approaches (Gibbons 2000). This flow reflects the O’Connor and Daniels (2001) idea that service trade is strongest between nations that are in fact high level service producers already. The attraction of the US graduate school system illustrates that type of trade. At the same time, there will be a flow of students out of countries where the domestic education system is small and constrained by local budgetary limitations, illustrating that world trade is still be between places of low supply and places of specialist levels of production. The movement of Asian students in search of undergraduate (and even final year high school education) illustrates that flow. These two outcomes indicate that the internationalisation of education can be seen as a natural outcome of structural economic change favouring knowledge intensive activities which has stimulated a demand for education in another system. It has also been expressed in collaboration between institutions across different educational systems seen in national policy in the Netherlands (Callan 2000, Johnson 1997). A third dimension has been a crude financial one expressed by both national governments and institutions. For governments that has involved an understanding of education as a significant part of national trade policy. This perspective has crept into the discussion of international education only recently. It can be seen in the acknowledgement that education is now seen as a “tradable activity” rather than a stimulus to curriculum and student educational aspirations (Elliott 2000:33). In fact Booth (2000:42) notes that the Dearing Committee Report in the UK in 1998 “took account of higher education’s international role per se largely…. in terms of the ability to trade educational goods and services successfully in the global market-place”. This perspective was adopted earlier in some countries (notably Australia and Canada). For many institutions, the significance of trade in education services is now central to financial survival especially where national governments have decided not to fund operations as well as they have in the past. As Bruch and Barty (2000: 22) note “ ….virtually all higher education institutions would feel a very firm pinch if the income from international students dried up. Some departments or units , particularly at postgraduate level, would be threatened with closure”. Institutions have responded to the income potential of international students in a variety of ways, most commonly attracting students to their current locations but some are moving into foreign countries to deliver education in owned or joint-venture initiatives, especially in Asia. So whether motivated by curriculum enrichment, personal of national financial interest the export of education on a global scale is now a significant activity. It has a special relevance to cities because it has one very unique feature compared to most other service exports. With education the buyer (ie the student) has to travel and live in the producing country ( ie the University or College campus) usually for an extended period of time, whereas most service exports involve the supplier visiting the buyer for short selling and follow-up service missions. At the same time educational institutions are usually in urban areas, although these can varying in size and location. Hence the export of education is likely to have a very substantial urban impact expressed in the employment of teaching and administrative staff, student housing, and other student consumption spread over three or more years. If there is some geographic selectivity in the movement of students, either in favour of some countries or some cities, then the global trade in education services could be associated with differences in urban development. Taken further it is possible that the export of educational services could begin to re-shape the global roles of some cities just as we now understand global commercial services shape the hierarchy of global cities. As noted earlier the export of education services has a number of different forms. Although traditionally associated with graduate training of a very select group of students it now involves both undergraduate as well as secondary education, along with specially targeted English language training, special trade and dedicated skill courses and focused short courses for professionals. That diversity of activity makes it difficult to generalise about the export of education services, although at the present time tertiary education (both undergraduate and post graduate) is the dominant area in terms of numbers (although enrolments are growing rapidly in some of the other educational areas). In the subsequent analysis the tertiary sector will be the focus of attention. GLOBAL PATTERNS IN TRADE IN TERTIARY EDUCATIONThe scale of global education can be established with the use of data published by UNESCO (see table 1). Although the numbers recorded for some countries do not correspond to the numbers recorded in some national data series ( that applies to the US and Australia) this source is the only one readily available to paint a broad picture of the scale of this activity. The data shows how international movement of students is focused on two major suppliers (the UK and the US) which together account for forty percent of the enrolment recorded in this data base. Two large European education systems (Germany and France) rank next, followed by Australia which in per capita terms is perhaps the country most intensively involved in this activity. This small number of countries account for two thirds of international tertiary student enrolments. It is also possible to trace the movement of students on at least a continental scale with this information. Data in table 2 show that the flow of students tends to fit the idea that there are a number of trading blocs in the world. Hence there are strong flows between the US and Asia, within Europe (for UK, France and Germany) and between Europe and Africa (for France). The strong link between Australia and Asia reflects that country’s broader trade patterns as shown by O’Connor and Daniels (2001). Hence the export of tertiary education can be understood using traditional trade perspectives (from areas of under supply to areas of production), while at the same time it incorporates dimensions of trade exposed by Storper (2000) where trade flows between parts of the world that do in fact have well developed local supply, like the exchange of students within Europe, between the US and Canada and Europe, and within North America. The pattern captured in table 1 does not capture the rapid growth that has been experienced in this sector. The latter is displayed in the steady growth in enrolments even in the past decade in the four countries for which data of this kind is most readily available. This material establishes that the trade in tertiary education is a large and rapidly growing activity.

Table 1: International Tertiary Students Enrolled in Countries, 1999

Source:UNESCO (2003). Some values refer to 2002/03.

Table 2: Origins of Students of Major Education Providers

Figure 1

The aspects outlined above suggests a number of important features about the export of tertiary education. The first is the scale of education services within the supply countries acts as an attraction. This would account for the significant role played by the US, UK, Germany and France where capacity at home, built originally for domestic students, provides the foundation for exports. It is also likely that English language is important so reinforcing the role of the US and the UK, but bringing Australia and Canada into the reckoning. Finally the data shows the importance of national trade policy. Australia and Canada have been particularly prominent in this regard, looking to meet the growing demand for education from the Asian market and providing special visa classes to facilitate the movement of students. Attention now turns to the impact of this activity on cities. THE EXPORT OF TERTIARY EDUCATION AND CITIES: A CASE STUDY OF US, UK, AUSTRALIA AND CANADAThe urban impact of the export of tertiary services depends on the location, scale and individual policy of institutions. At an individual level institutions can shape their export role through their decisions on fee structures, as well as by policies adopted on admission standards and forms of enrolment, which might in some cases emphasise post graduate courses, while in others include both undergraduate and post graduate courses. For urban areas the impact will be influenced by the number and scale of their institutions that have engaged in education export. In some cases there could be several institutions, while in others there may only be one. Generally institutions seek out export opportunities separately and act in competition with one another, although in some cases broader city organizations or state and provincial governments provide an auspice for promotion and follow-up on enrolments for institutions within a city. In this first step to understand the urban impact of the export of tertiary education services it is possible to get information on the enrolment of students in cities in the US and Canada (institutions assigned to MSA’s in the US by the IIE network and to CMAs in Canada by Statistics Canada); for the UK and Australia institutions were assigned to cities by the author, and enrolments of international students at institutions summed for each city. Actual international student enrolments in Canadian cities were not available at the time of writing so numbers are estimated from data on all international students (secondary, tertiary and other courses). This may underestimate the scale of tertiary education in the major cities where large institutions have substantial international enrolments. The information is sensitive to spatial unit definition especially in the US as illustrated in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The data presented for Census Metropolitan Areas reported numbers separately for San Francisco and Oakland as well as for Los Angeles and Orange County. For the current research, interest lay in a global city region perspective so that these census units were merged to create data for the larger scale extended metropolitan area. That approach was adopted for London, where institutions on the fringe of the metropolitan area were assigned to “London”. The global hierarchy of (Anglo Saxon) global city regions with at least 5,000 international students enrolled is displayed in table 3.

Table 3: Numbers of International Students in Metropolitan Areas in Australia, Canada, UK and USA.

*Students estimated from total foreign student enrollments using the national Canadian average of 45% of all foreign students in tertiary enrolment. Note: Numbers listed are the total enrolled in the institutions in each city. Some institutions have off shore operations; these have not been separated at this stage as consistent data is not available. Others operate multi campus operations: two Australian institutions record enrolments of 7274 in Rockhampton and 6406 in Toowoomba however these students are dispersed across campuses in several cities including Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane; precise details of actual student enrolment by city are not available at this stage. It is likely that these numbers would increase the numbers of international students in some of the major Australian cities. Sources:

Table 4: Comparison of City Rank: GaWC Hierarchy and Tertiary Education Numbers

An initial hierarchy of cities has been created ranking in terms of numbers and identifying major breaks in the list as shown in table 4. That hierarchy in column three of table 4 confirms the established global city hierarchy, with prominent roles for London, New York and Los Angeles, but at the same time shows that there are some “international education education cities” where global rank is higher than in the Global and World City hierarchy displayed for these cities in column two. Cities such as Melbourne, Sydney as well as Boston, San Francisco and Philadelphia, stand out as significant tertiary student destinations and rank much higher than is their commercial roles would suggest. In contrast Chicago, Dallas and Houston rank lower as educational destinations. Further down the hierarchy, places like Seattle and Oxford are prominent in education but not in the commercially based GaWC hierarchy. There are a number of explanatory factors for this international tertiary education hierarchy of cities. The first is the stance taken in national education policy which has a significant impact on the role of the Australian and Canadian cities. The differences in the roles of these cities also reflects a number of factors in the organization and spatial distributions of educational institutions within a nation. That influence is best illustrated in a comparison of the numbers of international students at the ten most important US and Australian institutions, shown in table 5 and 6. In the Australian case seven of the institutions with the largest numbers of students are in either Melbourne or Sydney; the multi-campus institution also has operations in those cities which could boost their numbers even further. In contrast in the US six of the ten largest locations of international students are in small cities. That effect may also account for the lack of UK cities included in this list, even though London in the world’s pre-eminent destination. UK institutions are distributed across many cities so reducing the impact of international enrolment on any one city. Note also that five of the leading Australian institutions have twenty or more per cent of their enrolment as international students; in the US that level is reached by only two institutions. In the Australian case an aggressive national policy on foreign student enrolment allied to a concentrated pattern of educational institutions has created globally prominent cities. Although data was unavailable for France and Germany it is likely that the concentration of major institutions in Paris would underscore its role in this hierarchy, while the dispersal of German institutions across a range of city sizes many limit the impact of international student enrolment at any one city.

Table 5: International Student Enrolments: Ten Largest Australian Institutions.

Table 6: International Student Enrolment: Ten Largest US Institutions

The perceived quality of institutions within the cities listed obviously plays a role in determining international student enrolment. Two recent rankings of institutions were interrogated to produce the information displayed in columns three and four of table 3. These two rankings use different criteria, and also count different numbers of institutions. For the current purposes interest centred on the higher ranked institutions. A simple measure was used: only institutions ranked in the top 100 were counted. This was seen as an indication of high quality institution. In general the higher ranked cities have more high ranked institutions; however in some cases, such as Boston, a good record here has not been sufficient to lift student numbers. This stage of the research has established that the export of education, as reflected in international students located in cities, provides a new perspective on the global role of some cities. At one level it enriches our understanding of the role that London, New York and Los Angeles play in global activity. Though prominent in the arrangement of international commercial services and connections to headquarter functions, these places are also targets for international students attracted in some cases by the quality of institutions, but perhaps also by their economic, social and cultural dimensions. That means the globalization of these cities will be expressed through a large short-term resident population drawn from other parts of the world, adding to migrant communities that have established there in response to local labour market opportunities. At the same time the data has drawn attention to the global role of a set of smaller cities, places that have a lower profile in networks of commercial services and links to headquarter functions. Their large numbers of international students make these cities “global” in a very particular way. That impact is especially significant in some of the second ranked cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Melbourne and Montreal where the global commercial links of their national urban networks have tended to be focused on a larger city (like New York, Sydney, Toronto). These cities now have an alternative stream of global connections and through that will express an influence upon other parts of the world. Within these cities the international students have an impact on the character of local populations as their consumption of housing and retail and related services during their time in the city adds a new dimension to local population and service functions. At the same time the institutions can expand, employing more staff and building new facilities, so adding to the economic structure of the city. These outcomes are even more prominent when they occur in places like Brisbane, Vancouver, and Seattle which to date have had weak local expressions of international business connections. In these ways international students create a dimension in city development over and above their direct financial and economic impact which is the traditional focus of the impact of education on cities (as illustrated in the series of papers edited by van der Wusten, H. 1997). THE LOCAL SCALE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF MELBOURNEThe second objective of the current project has been to establish a measure of the local impact of the broader version of global linkages emphasised here. In the current context that impact might be expressed in the location of the major educational institutions. In many cities educational institutions are located in inner city sites, but in some cities newer, younger institutions operate from suburban locations. A potentially informative measure of the local impact of educational institutions is the residential location of their international students, which will provide an expression of housing and probably retail and other service impacts. A further measure could be a local labour market measure, based on the home location of the staff of each institution. It might be possible to ascribe part of the size of the labour catchment to the international student enrolment: that approach is not employed at this stage due to conceptual and data difficulties in its implementation. As noted in table 3 Melbourne is a globally significant destination for international students. In the national context too it is very prominent, accounting for one third of Australia’s international students, although as a metropolitan area it has just 18% of the nation’s population. These students are enrolled predominantly in six institutions, two in the CBD (Melbourne University and RMIT) and four in the suburbs ( Monash, Deakin, Latrobe, Swinburne and VUT; Deakin also has a campus in Geelong, a city on the edge of the Melbourne global city region). Some of the suburban institutions, ( as well as some interstate institutions) have small teaching facilities in the CBD; their activity is not included in the information displayed in table 7 so the absolute scale of tertiary education in the CBD is slightly under-estimated.

Table 7: International Student Enrolment in Melbourne Tertiary Institutions

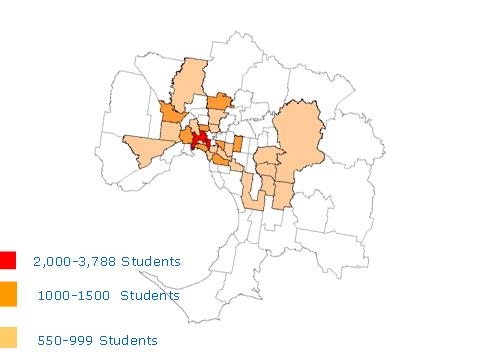

This data suggests that almost two thirds of the very large globally-focused education activity in Melbourne is located in the suburbs. As noted earlier however, the more fundamental impact of student enrolment will be felt through residential location, and figure 2 shows international students in parts of municipalities in Melbourne in 2001. This is drawn from census data rather than institution records so shows where all international students regardless of institution of enrolment have elected to live in the metropolitan area.

Figure 2: Residential Location of International Tertiary Students Melbourne 2001

An inner city ring of municipalities accounts for the majority of international student residential locations. That reflects in part the provision of special purpose student housing by developers in and around the CBD. This was an important part of inner city housing construction in the early and mid 1990s (O’Connor 2004), and provided an opportunity for many students even if enrolled at a suburban campus. The map also shows there are important clusters of residential areas associated with Monash and Deakin in the south east, Latrobe in the north and VUT in the west. Apart from the small gain in the share living in the inner city, the relative size of those clusters of housing locations has not changed much over the 1991-2001 period even though overall numbers have grown by 30%, as can be seen in table 8.

Table 8: Residential Location of International Students in parts of Melbourne 1991-2001

The data displayed here shows that large numbers of students gather in a few sub-regions of the metropolitan area. In a number of these sub-regions they have gathered in sufficient numbers to add another dimension to the already diverse ethnic character of suburban Melbourne; it is possible that they may have begun to change the character of local retail and commercial activity in some areas. In the process they illustrate that globally significant economic activity can have a diffuse effect upon the structure and operation of a metropolitan region. CONCLUSIONSThe research reported here has shown that a particular form of globalisation (the export of education services) has led to the movement of large numbers of students to a few places and in turn has created a new layer in the activity of global cities. That layer is disproportionately thick in a few places, some of which have long been seen as global cities; others are just creating this role for themselves as their national education systems shift rapidly toward international student enrolment. In some countries this global effect is dissipated among many institutions in smaller cities, creating global functions in cities rarely considered in global city discussions. Hence Urbana Champaign, Ann Arbor, Madison, and Columbus in the US along with Durham, Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge in the UK (and perhaps some smaller French German and Dutch cities) house large numbers of international students but do not figure as global cities. In this way it seems the global city effect of international students depends in part upon national structures and management of higher education in the same way as the global impact of manufacturing depends upon national protection and trade policy. The location of institutions also shapes the local or intra city impact, as illustrated in the Melbourne case study. There enrolment, and residential development associated with enrolment, has to date emphasised the suburbs as much as the inner city. The research begs the question of the way that students select institution and city and so can not provide a deeper understanding of this element of global city development. Crude measures of institution quality do seem to have some connection to the pattern of aggregate movement, but whether that is the determining feature in student choice is unknown at present. Similarly whether the student selects the city first, and then the institution, deserves some consideration as it implies the “global presence” of a city (perhaps emanating from its commercial and cultural reputation) could be the driving force in the attractiveness of its local institutions. If that were the case then the export of education services is simply something that can be added to the strong relationships of established global cities. If however institutions have drawing power in some way separate to the character of their city (which could apply to major US universities in smaller cities) then the export of educational services may be a very different force within global city development. Dealing with educational institutions as the expression of global links introduces some unusual features to the understanding of these cities. Many other sectors of production can be understood and interpreted using an intellectual frameworks that utilize ideas about the interlinkages and networks of producers and the benefits of clustering which are enriched in special ways in larger cities. This is expressed in perhaps the most direct way in Sassen’s (2000) idea of the “production complex” of advanced services. It is unlikely that this set of ideas will be useful in developing ideas about the location and vitality of educational institutions in a city which almost by definition are in competition with one another for students and research funds and have few incentives to collaborate locally. However if the city’s interests are in maximizing the number of international students then some collaboration between local institutions could be valuable. This might require a state or local government initiative. Looking beyond the detailed issues surrounding education, the research has established that global trade flows can produce some different global city linkages and local outcomes. This perspective could be broadened to other aspects of global trade. A significant part of manufacturing, along with some related advanced services like industrial design for example, involves reciprocal trade connections between countries. Here too the location of the producers is not necessarily governed by the global city logic that emanates from the commercial services sector. In fact many small German, Japanese Italian and British cities may have global functions because they are the home location of advanced manufacturers and service firms. As an example a recent Economist (2004) survey of Japanese manufacturing shows many global market-segment leaders in research and development intensive electronics and optics products are located in small and mid sized cities. So our understanding and description of global cities in the future we may need to recognise categories of places that provide specialist global functions, and through them have complex relationships with many other places across the globe, but will not have the diversity of function (nor the size) that we currently associate with global cities. It is possible (in fact likely) that this broader array of globally-linked firms could still favour the global city regions that surround the corporate core of the global city. They will be drawn there by the infrastructure, creativity and labour market density of these locations as outlined by Simmonds and Hack (2000). In that way their location and production will be contributing to development in the range of locations identified within a global city region by Hall (2001). These possibilities enrich the way that global city research can contribute to the understanding of modern urban outcomes. REFERENCESAlderson, A.S. and Beckfield, J. (2002) Power and Position in the World City System, American Journal of Sociology, 109, 811-851. Beaverstock, J V., Smith, R.G., and Taylor, P.J. (1999) A Roster of World Cities, Cities 16 (6), 445-458. Booth, C (200) Afterword, in Scott, P (ed) The Globalisation of Higher Education. Buckingham. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Page 42-43 Bruch, T., and Barty, A (2000) Internationalizing British Higher Education; Students and Institutions, in Scott, P (ed) The Globalisation of Higher Education. Buckingham. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Page 18-31. Callan, H (2000) Internationalisation in Europe, in Scott, P (ed) The Globalisation of Higher Education. Buckingham. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Page 44-57 The Economist (2004) Special Report: Manufacturing in Japan: (Still) Made in Japan, The Economist, 371 (8370), April 10. Page 57-593 Elliott, D. Internationalizing British Higher Education: policy perspectives, in Scott, P (ed) The Globalisation of Higher Education. Buckingham. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Page 32-43 Friedmann, J. (1986) The World City Hypothesis. Development and Change, 17, 69-84. Gibbons, M. (2000) A Commonwealth Perspective on the Globalisation of Higher Education, in Scott, P (ed) The Globalisation of Higher Education. Buckingham. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Page 70-87 Hack, G. (2000) Infrastructure and Regional Form, in Simmonds, R., and Hack, G (eds) Global City Regions. Their Emerging Forms. London. Spon Press. Pages 183-192 Hall, P. (2001) Global City Regions in the Twenty First Century, in Scott, A (ed) City Regions. Trends, Theory, Policy. Oxford. Oxford UP. Pages 59-77. Johnson, L. (1997) The Internationisation of Higher Education in the Netherlands, Journal of International Education, 8, 28-35. Knight, J. (1997) Internationalisation of Higher Education: A Conceptual Framework, in Knight, J., and de Wit, H (eds) Internationalisation of Higher Education in Asia Pacific Countries. Amsterdam. European Association for International Education. Page 11-22 Krätke, S., and Taylor. P.J. (2003) A World Geography of Global Media Cities, GaWC Research Bulletin 96. Department of Geography. University of Loughborough. McGee, T .G. (1994) Labour Force Change and Mobility in the Extended Metropolitan Regions of Asia, in Fuchs, R., Brennan, E., Chamie, J., Lo, F-C., and Uitto, J (eds) Mega City Growth and the Future. Tokyo: United Nations University Press. Page 62-102 O’Connor, K. (2002) Rethinking Globalisation and Urban Development: The Fortunes of Second-ranked Cities. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 8 (3) 247-260. also GaWC Research Bulletin 118. Department of Geography University of Loughborough . O’Connor, K (2004) The Inner City Apartment Market: Review and Prospect. Melbourne . The Property Council of Australia, Victorian Division. O’Connor, K. and P. Daniels (2001) The Geography of International Trade in Services: Australia and the APEC Region, Environment and Planning A 33, 281-296. Reich, R (1992) The Work of Nations. Preparing Ourselves for 21 st Century Capitalism. New York. Vintage Books. Romer, P (1990) Endogeneous Technology Change, Journal of Political Economy, 98, 71-102. Sassen S (2000) Cities in a World Economy. Second edition. London. Pine Forge Press Scott, A. (ed) (2001) Global City Regions. Trends, Theory, Policy. Oxford. Oxford UP. Simmonds R., and Hack G. (2000) (eds) Global City Regions: Their Emerging Forms. London Spon Press. Storper (2000) Globalisation and Knowledge Flows: An Industrial Geographers Perspective, in Dunning, J (ed) Regions, Globalisation and The Knowledge Based Economy . Oxford. Oxford U.P. Page 42-62. Taylor , P. (2003) Zurich as a World City. GaWC Research Bulletin 112. Department of Geography University of Loughborough. Taylor , P (2004) World City Network. A Global Urban Analysis. London Routledge. Townsend, A (2001) The Internet and the Rise of the New network cities, 1969-1999, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 28, 39-58. van der Wusten, H. (1997) Foreword, Special Issue on Universities and Cities, GeoJournal, 41, Issue 4. NOTE* Kevin O’Connor, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne, Kevin.oconnor@unimelb.edu.au Edited and posted on the web on 17th February 2005 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||