GaWC Research Bulletin 472 |

|

|

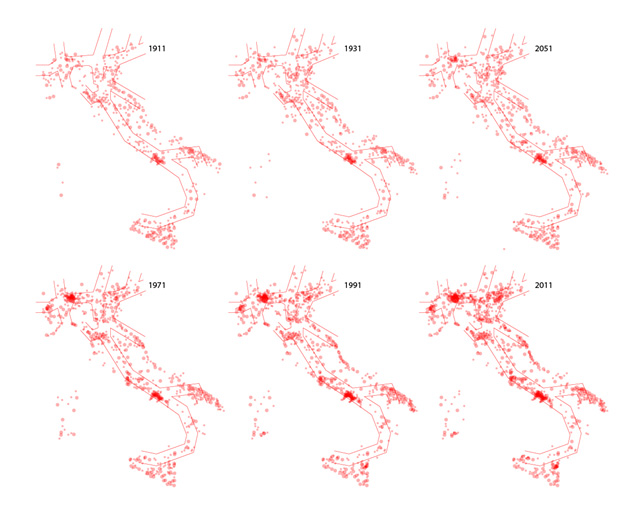

The new economic base of the cityThe economic base of contemporary cities is changing. We can start from two traits: the internationalization of economic systems and the flexible informalization of labour markets and relations connected to a strong growth of functional urban services. Hence the cities open to new geographies both of industrialisation and territorial development. The crossover between these two dimensions (Storper, Walker 1989) used to occur in the urban environment, today it extends over new and broadened city-regional scales. The economy is today largely diffused across territories and distributed in long value-chains, yet its base is within cities. On the one hand there is the city’s territory, on the other the flows (of activities made in the world and hence perennially on the move, of non resident, migrant population) that seem to be exponentially growing in all directions within and between territories. Migrants are 191 million the world over, a small percentage of the world population (3%). But of these 64 million are in Europe, 53 in Asia and 44 in America. In a country like Germany the workforce is 14% foreign, the figure is 17% in Spain, 12% in France, 16% in the US. The largest part of the flows is concentrated in cities: in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Brussels between ¼ and 1/3 of the population is foreign, in London the figure is 21.1%; a 1/3 of the population of New York is foreign; in Toronto and Vancouver foreigners make up more than 40% of the population (Therborn 2011). A second starting question concerns the region, that at the beginning traces out borders that are sacred and impassable. Can this now be a borderless region? Because when we today speak of regions we define territories that have no precise borders, whose production activities are a lot more delocated than in the past. Safe to say there are the region’s administrative borders, but these are now perforated and crossed by flows of all types and all directions. Any region, and in particular those bordering on other countries, are affected by these trans-frontier dynamics. The regions of Northern Italy are an example: the Ligurian ports are points of transit towards the North of Italy, Lombardy is a platform for people and goods on the move across regions and firms, and the logic of hubs that attract and distribute resources and people involves the airports as it does the universities, the fairs just like the huge service centres. But the same goes for other European city-regions. Hence from an administrative point of view, the region has only limited effects on the socio-economic dynamics that traverse the territories. The coordination of spatial, functional and sectoral dimensions is the reason for impressive institutional change (Salet, Thornley and Kreukels 2003). And it is not by chance that urban scholars at the beginning of this century have coined new terms, like ‘postmetropolis’ (Soja 2000) and ‘global city-region’(Scott 2001). What is then the world made up of? It is made up of global city-regions that are no longer cities nor traditional regions. They are an amalgam, new mixtures of economy and society (the theme of mixing, of mixed, of the place of opposites is typical of our contemporary time). They don’t have a precise political or institutional representation: perhaps they are in search of it. And tendentially they are global city-regions in the sense that the flows that traverse these territories are not territorially located, neither can they be confined in a city or regional dimension, but they are global in nature. Technology drives the world, immaterial and a-territorial as it is. Hence has this process of loss of places and centres, this deployment reached the point of impeding any margin, edge or limit to the global world? Have urbs and orbis come to mean “everywhere and no matter where”, as Jean-Luc Nancy (2002) writes? These are the questions we must ask in that, wherever we are positioned or deployed, we inevitably belong to this dimension. A dimension that certainly presents different characteristics according to the contexts, the continents. Without a doubt the European city preserves historic-political peculiarities (Le Galés 2002 has convincingly developed the Weberian argument), but this is the global challenge that lies before us. The European global city-regionIn the text inaugurating the global city-region literature (Scott 2001) a table listed the first thirty in the world. Tokyo leads the way with 28 million inhabitants calculated in 2015, followed by many third world and few Western cities (in Europe: London and Paris). No South European city is ranked among the first: but if we consider Milan as a global city-region in Northern Italy (a macroregion of 26 million inhabitants), it would be up among the first places. As Bagnasco (2010) suggests, it is much wider than other European regions like Bavaria or Catalunya: yet it is a polycentric, multi-clustered and cross-border region of flows. In Castells’ terms it is a “spaces of flow”. The possibility of defining a city appears strongly undermined once the world can only aboveall be read as a world of flows, that belong to types of relations that escape control at a given point. That is to say the city can be a point, a node or junction, but these flows can in no way be identified with a spatial governance. And perhaps here lies the strongest impediment. Because throughout the twentieth century we thought that this spatial control was still possible in the metropolitan form. It was said that the governance and the control were entrusted to the city and its metropolitan forms: even in a highly articulate way (like the “thousand governments” of the American city) but all the same identifiable as units. It is in this point that the Simmelian metropolitan intellect in terms of force capable of ordering the space, is most undermined. Today we see ever less spatial governance. Rather what we perceive before us is anomia, loss of capacity of governance, the traversal of flows of a physical, immaterial and virtual type in all directions. These flows do not follow an organized pattern, nor a form capable of being governed. They are the product of market forces, of anonymous matrixes, of complex interdependencies. In some cases like that of the telematics networks or mobility infrastructures the most we can do is identify actors or decision-makers who decide to invest in building a network. But the way in which myriads of actors behave, deploy, receive signals and use these networks defies any pattern or governance. Here one has the old and new asymmetries that characterise the contemporary city. The main asymmetry to be tackled with is information access, which is highly selective. It is a matter of digital divide, including training and retraining and the creation of ‘smart’ communities not limited to privileged economic élites. In the case of European cities recent research has measured the large amount of firms which are excluded or under-represented in the access to ICT (Information and Communication Technologies). In comparative research among European cities, four types are identified (Derudder 2012): cities where the Internet has made an increase of GDP possible (London, Paris, Frankfurt, Stockholm among them); cities where GDP increase has pushed the Internet (Brno, Graz, Turin among them); cities where both the Internet and GDP are correlated (Goteborg, Koln); cities where non correlation between the Internet and GDP has been found (like Milan, Wien, Brussels, Madrid, Barcelona, Athens). The variance is probably explained by the different institutional and contractual structures linking cities, enterprises and other functional and social actors. The second asymmetry is about mobility, which is still more selective: those who can move and shift, those who simply cannot. Financial markets are much more mobile than countries and enterprises; this is why global cities like London and New York and their National governments protect their financial markets from regulations. Also multinational firms are more mobile than countries in which they are located; this is why multinational firms can play with territories through localization and delocalization choices. Among firms, big buyers can move more easily (and actively do that) than sub-contractors which are mainly local in nature; but also world experts are more mobile than their client enterprises; firms are more mobile than their contingent labour force; and so on. Also in this case the contractual relations among different functional and social actors is a key explaining variable. All this is within a global city-regions. It is a platform where firms can land and take-off according to their strategies. But it is also an interconnected network of enterprises, institutions and people reciprocally interrelated by contracts. Who governs the European global city-region? A mix of Europe, State, region, city? A governance without government (Le Galés 2011)? On a normative ground, governance mechanisms should include new soft agreements and new constitutional orderings. Soft agreements are a case of unwritten, informal contracts. They have to be managed by territorial governments and interest associations or ‘secondary citizens’ (chambers of commerce, interest organizations and a myriad of citizens’ associations) to create a common understanding and common rules of conduct. This is a matter of both implicit and explicit contracting among different actors and stakeholders: think to human capital (training for which kind of labour markets, local or global? Why local schools and universities should invest in training skilled workforce destined to migrate to other countries?), externalities (how to locally manage the environment and global common goods? Are localities able to consider larger horizons in time and space?), and networks (density of heterogeneous people within a territory was the distinctive feature of urbanity in the past, today it is the degree of global openness and participation in any kind of multinational networks which makes the difference). The attraction and regulation of material and immaterial flows is the main issue to be governed. It is not a novelty in the history of capitalism, but novel is the dimension of property rights of knowledge circulating in the world economy. We even have problems measuring and representing such flows, because official statistics ignore the same: the persons and enterprises are counted and included but not the volumes or the values of immaterial flows in transit across territories. We haven’t got beyond the statistics of the Nation-State of the 17th-18th century at the origin of modern sovereignty, while the contemporary world is forged by global flows. The resorting to a morphology of “spaces of flow” would be useful. It is a matter of underlining these novel aspects, even if economic flows certainly haven’t come into being today. According to Braudel the Europe of the Renaissance was already a circulation of flows. All the same these were other flows, the dimensions were different and so too were space-time relations. Hence the main themes of contemporary problematique are strong signs of a spatial crisis. In the era of global flows and disjointments (Appadurai 1996) the city risks losing out as a point that orders space, because of the phenomenon of deterritorialisation and creation of diasporic arenas as a result of global migration. Hence one has to reflect on this aspect and what new models are emerging from the point of view of city analysis. Brenner (2010) asserts that the “cityness” of the city has been the object of naturalisation by urban studies, and that “city” and “urban” are not real or empirical elements but structural projects continuously re-created during the spatial production of capitalism. The units of analysis of “city” and “urban” are to be understood themselves as continuously co-constructed and reconstructed: the cityness of the city is a condition that is evolving continuously, multiscale and the object of strategic contestation in geopolitical relations, rather than an object or a territorially delineated site. The risk of reifying the city turning it into a collective actor can be avoided resorting systematically to network analysis like in Latourian Actor-Network Theory (critically reviewed in Brenner et al. 2012). Cities are “networks of networks” of actors: enterprises in productive networks, persons in mobility and communications networks, institutions in policy networks. Hence only for simplicity’s sake do we speak of “city-regions”: in actual fact we are speaking of networks of networks (or “assemblage of assemblages”). The ontology of global city-region as a “web of contracts” fits well into the assemblage theory. The scale and territory are not given but constructed in a non-uniform way, depending on the different scale, scope and functional entities taken into account. The global city-region is certainly a theme on which to reflect in the fluid, extended dimension today imposed by the economy and society. It is hardly a politico-institutional dimension already known. Does the global city-region of Northern Italy have a connotation that we can define (Perulli, Pichierri 2010)? Is it a “city-region”? Probably this is an interesting approach: more than a city-region in the sense used by Californian geographers to formulate this idea, it is a “region of cities”. A particular polynuclear fabric that thickens into networks that are ever less locally, evermore macroregionally and globally defined (towards France and Germany, Eastern Europe and increasingly Asia ). But the “global city-region” of Northern Italy is certainly also interesting for its global flows (2.5 million foreign residents in 2008) that are growing and placing the city-form as known up to now to the test. Urban Italy as a postmetropolitan space of flows: city-regions, middle-sized cities and corridorsEvolution of Italian Middle-Sized CitiesPopulation: 10.000-50.000 (Source:ISTAT)

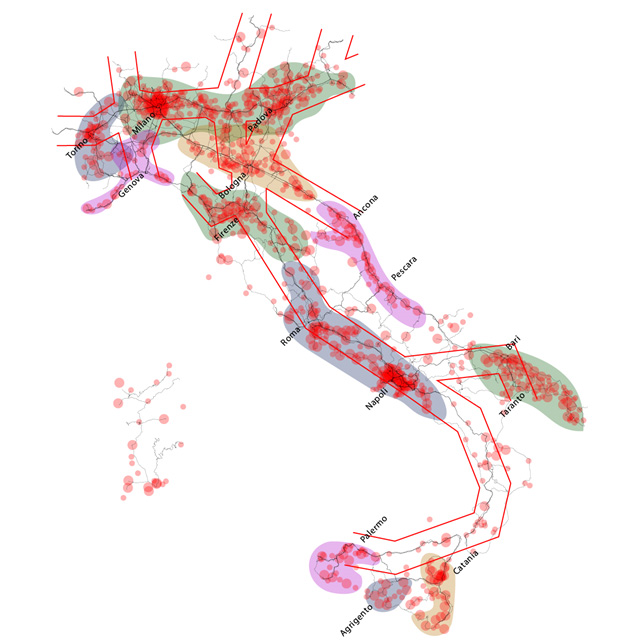

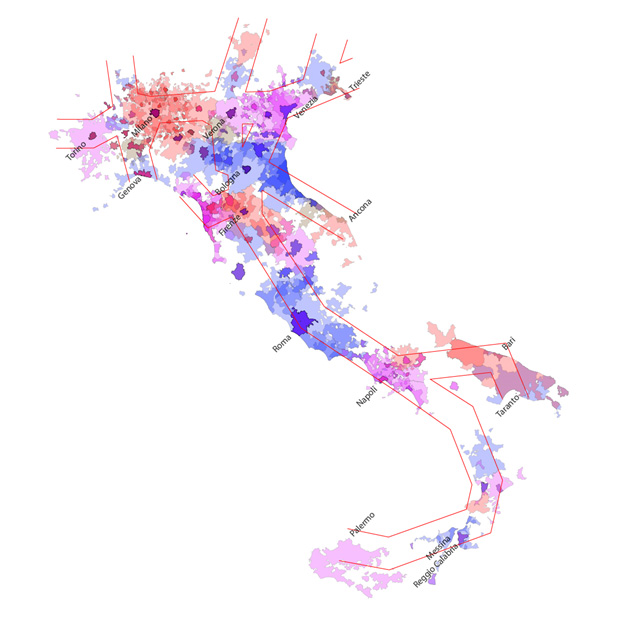

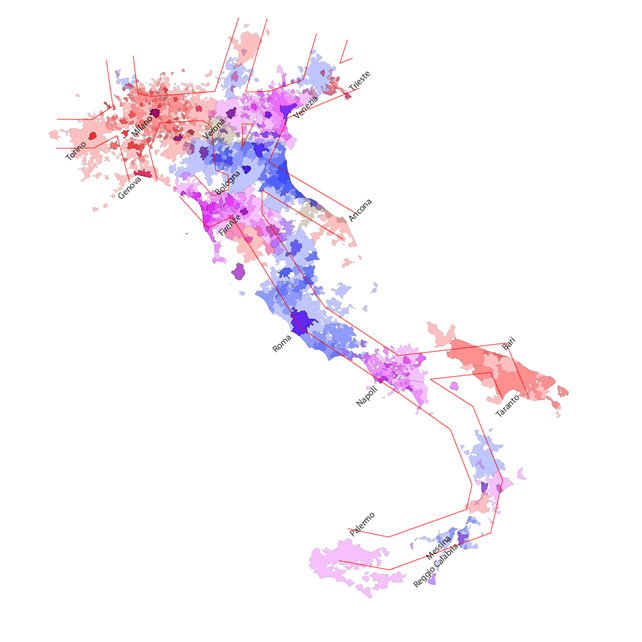

Looking at the evolution of the Italian cities, classified by population, it is possible to notice the emergence of some axes of territorial development. We can divide the cities in three main groups: small towns, with less then 10.000 inhabitants; middle-sized cities with 10.000-50.000 inhabitants; main centres with more than 50.000 inhabitants. Between 1911 and 2011 the number of middle-sized cities more than doubled from 491 to 1054. The evolution of the distribution of this class of cities is the most useful mark to understand the emerging of some specific corridors of territorial development. Looking at the maps we can see two different process: the first one is the growth of the cities around the most important centres of the nation and the formation of the main metropolitan areas (Milan, Turin, Rome, …); the second process, started during the 1970’s is the growth of the cities between the main centres, forming specific territorial corridors. Main Territorial Corridors Identified by 2011 Middle-sized Cities DistributionIn the next map we can see a first hypothesis of classification of the main territorial corridors. Comparing these corridors with the path of the European Core Network Corridor (CNC) it is possible to understand if and where they converge or not. Notably: - While the Milan-Padua-Venice corridor is quite self-evident, the link between Milan and Turin is not as clear as the previous one. The distribution of the middle-sized cities in Piedmont follows the Alpine arch instead of the linear Milan-Turin-France direction. This result makes clear that physical infrastructures aren’t the determinant factor explaining city growth: they are rather a component of socio-economic territorial development. - When it comes to Southern Italy, the link between Naples and Bari or between Naples and Palermo stressed by the European Commission seems to be purely arbitrary. - On the other side the Adriatic Corridor and the Ligurian Arch are not part of the CNC and the junction between the Milan-Padua-Venice corridor and the Milan-Bologna one is completely missed in the CNC.

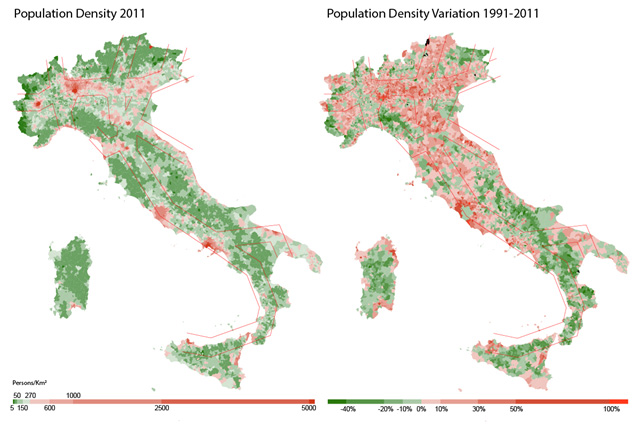

Source: ISTAT 2011 Evolution of Population DensityInhabitants/sq Km (municipal level)

Note - The left map represents the Population density rate in 2011. Municipalities with a density value lower than the average (270 Persons/sq Km) are in green. Municipalities with higher then average values are in red. The right map represents the population density rate variation between 1991 and 2011. In green the municipalities reducing the population density; in red the ones that increase the rate.(Source: ISTAT 2011) Looking at the population data it is really interesting to analyse the distribution of the inhabitant density. The map of population density in 2011 makes clear the stable existence of some important metropolitan areas (Turin, Rome, Naples) and regions (Lombardy and Veneto). There are also some other densely populated areas involving more than one main city, but not as big as the Lombardy and Veneto metropolitan region: The Ligurian Arch, the Tuscany axis Firenze-Prato-Pistoia-Pisa-Lucca-Livorno-La Spezia, the Emilian Way Piacenza-Parma-Reggio Emilia-Modena-Bologna, and the Adriatic Coast. Except Lombardy and Veneto regions that seem close to other densely populated areas, these axes are mainly isolated and surrounded by scarcely populated areas. The territorial corridors don’t seem as clear as in the previous map. However if we take into account the evolution of population density in the last 20 years the territorial corridors emerge clearly again. The growth of population density not only concerns the most dense areas (in red in the left map), but also the less dense areas surrounding the previous one. Moreover the previous hypotheses (like the lack of continuity between Turin and Milan or between Naples-Bari and Naples-Palermo and the presence of an Adriatic corridor) are confirmed and some interesting new findings emerge: - Apulia region doesn’t seem to be so homogeneous as before. There is a high presence of close middle-sized cities but this implies a territorial organization really different from what we call a territorial corridor. - The most dense areas between Florence and Rome don’t follow the path of the CNC. These areas include the main cities of Umbria region like Perugia (history matters). - The Trentino Alto-Adige region didn’t emerge from the previous analysis. Looking at the population density evolution it is a really evident region, as much as the rest of the Milan-Venice corridor. Daily Commuting Areas: Cross-Provincial Pependency

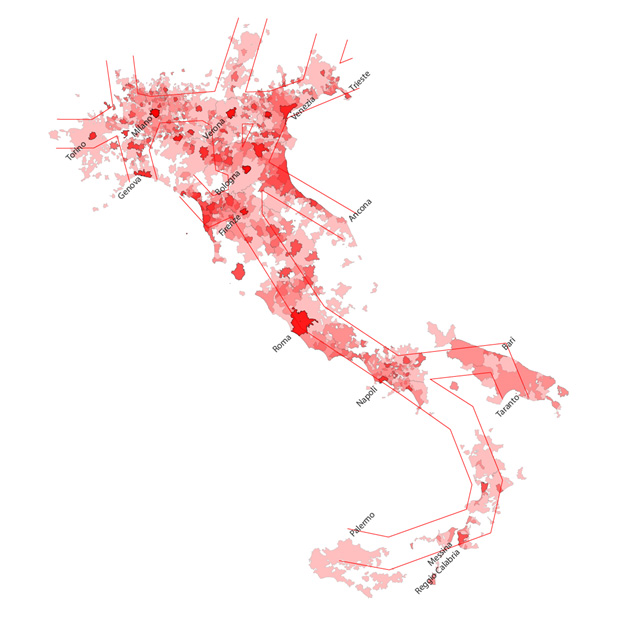

Note – The map represents the commuting areas for all the Provincial Capital crossed by the CNC. The commuting areas are drawn taking into account only the municipalities producing at least 50 commuters per day. The darker colors stress more overlap between the different Commuting Areas identifying the territories with high degree of cross-provincial dependency. (Source: ISTAT 2001) The commuting areas map identifies different territories characterized by a high level of interaction between Provinces. These are areas where flows of commuting are high and directed to many different destinations: the crown of the Milan Metropolitan area; the Veneto ‘diffused city’ between Verona and Venice; the axis between Milan and Ancona; the Florence-Tyrrhenian coast; the Rome-Naples axis.

Note – This map uses different colors to identify the areas highly interconnected by commuting flows. The Provincial Capitals that exchange at least 1000 commuter per day have their commuting area represented with the same color. Moreover, the use of transparency allows to identify territories where different colors overlap. (Source: ISTAT 2001) To better understand how this commuting flows impact on the territory we have taken into account the co-dependencies between the different Provincial Capitals. We have identified different Commuting Macro-Areas characterised by the flow of at least 1000 daily commuters from one main city to another. Using this criteria it would be possible to better identify the area inside the CNC that functions as a territorial corridor: not only characterised by dense and highly urbanized areas linearly structured, but also crossed by intense flows of moving people. The most interesting findings are: - The lack of direct link between Turin and Milan is confirmed. We can consider Turin and Milan as part of the same Macro-Area if we decrease the 1000 commuters threshold to 750. - The Milanese and the Venetian Commuting Macro-Areas are separated and with very little overlapping. - There is strong overlapping between the Venetian and the Bologna Macro-Areas. This overlapping area isn’t directly linked to the Adriatic corridor, but it is overlapping with the Milanese Macro-Area. - The Florentine and Tyrrhenian areas are not merged in a single Macro-Area but are hugely overlapped. These areas would form a single one if we decrease the 1000 commuters threshold to 800. - The Rome and Naples Macro-Areas are independent, but there still is a flow of commuters (almost 500) moving from Naples to Rome every day. - Southern Italy isn’t really characterized by cross-provincial commuting flows with the exception of the Messina-Reggio Calabria and the Bari-Barletta areas. These couldn’t be considered Macro-Areas as only two Provincial Capitals are involved really close to each other. In the next map it is possible to see how the Macro-Areas would change reducing the commuters threshold to 500 (instead of the 1000 threshold used before). Two main differences emerge: - The North-West of the country looks like a single huge Commuting Macro-area; - The Tuscany region is now a single Macro-area. There are also other small differences: - The Perugia commuting area is now part of the bigger Rome Macro-area. - Benevento is part of Naples Macro-area. - Taranto is now part of a Apulia Commuting Macro-area.

Note – This map uses a 500 commuters threshold to define the different Macro-Areas. (Source: ISTAT 2001) The following and final map shows the territorial distribution of internet routers in urban Italy. It is a proxy of connectivity and immaterial communications flows through cities and regions. Municipalities with more than 100 routers have been selected. The image follows perfectly the urbanization pattern showed in the previous maps. Source: CAIDA - IPv4 Routed /24 Topology Dataset - 07/2013 The relational-contract city: some empirical evidenceThe new direction of research proposed here concerns the connectivity of cities and of social systems they represent. We have been looking too long at cities as stocks of resources comparing the relative importance of them in terms of endowment of economic, social and cultural capital. We must now look at cities as connectivity nodes within networks of wider, tendentially global relations. Following this approach, which is inspired by the lesson given by J. Jacobs, the world is represented as a "blizzard of transactions" and this representation of flows allows us to go beyond the old image of the world as a mosaic of local systems. Peter Taylor (2004) has studied the network connectivity between global cities starting from advanced services (accounting, advertising, finance, insurance, legal, consulting) of 100 global companies located in 315 cities around the world, all exposed to globalization whether in central, peripheral and semi-peripheral locations. The degree each city is connected to the other, and to which ones, is the dependent variable of his research. Just mentioning Italy, what emerges is the strong position of Milan, which is in 8th place among world global cities, revealing an economic strenght that is disproportionate to its weak capacity of metropolitan governance (a series of loosely coupled institutionalized experiments in the Milan metropolitan region is examined in Gualini 2003). On the contrary Rome is only 53rd, confirming itself as political capital devoid of a global economic role. The map based on interfirm relations also shows that Milan is more interconnected to North America and Asia than to some other European cities. The relational-contractual ability of the city is hence the key element to be developed on the analytic side. It is a question of understanding the entirety of the contractual relations of the city: these are "many to many" contracts, both formal and informal, both explicit and implicit, as well as complete or incomplete. These contractual relationships are not exclusively typical of global city-regions, although here they are of utmost importance. Medium and small cities can also be interpreted in a relational-contractual approach. The contractual relationships to be investigated are more diverse than those between the State and the city. Moreover it is not a question of horizontal relationships (between local participants and community-based) versus vertical relationships (between the central State and the city). These two dimensions are intertwined and present together in forms which are often mixed, trans-local and transnational (Grote 2012). If developed in their potentials these trans-local and transnational contractual relations can free the city from what Charles Tilly (1992) has called ‘the prison of the Nation-State’. Seeing the dynamic relationships among cities of large transnational areas will allow us to create new contractual economic and power relationships. To rewrite the logics of influence, attraction, competition that guide the behavior of local participants but also to some extent, on a different scale, of the global players who operate on that territory. The contractual networks to be investigated are represented by businesses, groups, associations, supply chains, institutions, specialized centers, universities etc. The flows that feed these contractual networks are measurable flows of people, knowledge, material and immaterial resources and services. Contractual relationships between firms, shared research projects, industrial co-design, contracts that feed the knowledge flows can be analysed and represented. Examples are flows of human capital under training driven by contracts between local and foreign universities, knowledge flows through cooperation agreements established between industrial research centers located in different regions and countries, etc. In these research studies we discover the power of appeal and relations between places, something often difficult to measure. Prevalently qualitative research can then increase our understanding of the interaction mechanisms between actors in these relations. The importance of localization can also be measured by the presence of actors in networks that have been defined, alluding to industrial districts, new "hybrid collectives”. Many actors are involved in the creation of new industrial objects as result of the assemblages of practical knowledge and heterogeneous theories and thus contributing to the development of a new product: the networks are made up of designers, market analysts, vendors and buyers, developers from research and development departments, craftsmen and suppliers. These hybrid collectives are interrelated and in constant interaction, this being both local and remote (but without the former there cannot be the latter). But we could also consider illegal flows of capital, goods and persons which take part in globalization processes: from drugs to fiscal paradises to illegal transport of people from remote regions toward central cities. City networks in this perspective are networks of nodes that have different roles and different importance. Only a few nodes have sufficient critical mass and endowment of territorial capital (understood as a set of tangible and intangible assets) that would allow them to maintain global relations or develop extensive networks. Other nodes are undersized or shrinking. These latter nodes however can refer to the former exchanging resources with them on a more limited scale, but going further thanks to the main node represented by the “hub”-city. The contracts between hubs and nodes are worth studying. The hub-city has various functions to suit this purpose: they can be related to accessibility (road and rail, airport and port connections) and to receptivity (universities or specialized centers attracting students, tourists, visitors attracted by trade fairs, exhibitions and events) and international openness (various services). The combination between these different dimensions is what counts: the first places among the top European cities are held by those that have managed to combine a range of infrastructural, integrated transport services and attractiveness for businesses and individuals. In this sense the resources of creative activities and services offered by different local labour systems can also be compared. But we must go beyond this by studying the relationships between different nodes, though here it may be more a question of the lack of such relationships. In logistics terms cities are "gates", nodes of "extended gates" which include ports and inland terminals. A similar flow analysis must be made for airports, tourism and visits to cultural heritage sites, universities etc. In cognitive terms cities can participate in smart grids. This is about investigating the networks between and among companies. These are expressed in measurable relationships: partnerships between research centers and technological innovation (departments, associations, foundations, public research institutions, business centers, private research companies, service centers) needed to understand in which direction flows towards other cities, regions and countries are moving. Systematic relationships of companies with their suppliers and specialized service providers, and the geographical origins of management team can be observed. One can certainly and not only consider manufacturing companies but also the service industry, starting from financial and credit sectors. One should also think about business services (what is the market for these services in the presence of a developed manufacturing sector, or in the absence of the same?). These are areas that are often part of multinational groups, providing an additional constituent to our understanding of extended networks in areas where businesses are located. In this same framework intermediaries and development agencies promoted and financed by the public sector in various capacities can be taken into account, with the normative objective of proposing corrections and reinventions, to make good use of second-best instruments instead of using first-best badly (Rodrik 2004). Qualitative data allow us to understand the growth of localized firms, especially SMEs: their growth may not be in size, indeed it also may be of a relational-contractual type based on knowledge sharing via relationships of various kinds with other companies possessing complementary knowledge. But these same data, referring to different contexts such as those in Southern Italy, can lead to a better understanding of the dimension of crony capitalism, the contiguity between economy and politics and the ‘capture’ of public sector by interest groups. On a normative ground, in order to counteract these degenerative contractual phenomena, a central-local industrial policy could work as a coordination tool for stimulating investment and socializing risks through appropriate safeguards. The enterprises involved in ICT (information and communication technologies) play a particularly important role in the economy of flows. These concerns are by their very nature network linked. Milan is the main Italian Internet hub, the principal influx and departure point for main Italian and European Internet infrastructures. Yet Turin plays a special role in advanced technological research. Whilst small ICT businesses are developing in the metropolitan Veneto area. Here is an example of a global city-region in the forming. The cities of Southern Europe clearly suffer from insufficient growth of this sector, and this urgently asks for North-South re-equilibrium. After these studies on contractual relations and flows we will have the tools to better understand the stickiness of cities or industrial districts, “sticky places in slippery spaces” according to Ann Markusen (1996). We will gather facts to better understand the (in many ways mysterious) capacity of cities to attract and to create and add value . Rereading cities, territories and regions in this relational-contractual focus will allow us to understand and reposition each city, and the networks in which it participates in the global system. Afterwards our task will be to map out the possible, and not overriding institutional arrangements that will facilitate development: those that Dani Rodrik (2004) calls "the multiple ways of packing these principles into institutional arrangements". The capabilities to develop meaningful initiatives and agency amongst and between the actors mentioned here represent a central aspect. In some urban situations such agency capacity has been more developed than elsewhere, while in other cities in Southern Europe much less so. In such cases it may be useful to encourage the development of contractual-relational cities focusing on flows produced by exogenous shocks (direct foreign investments, tourist flows, company-hubs etc.). These flows could create opportunities for cities to react against decline, 'freeing' hidden local resources yet to be recognized and exploited. The proposal contained in this paper has attempted to seek out an analytical perspective different to that of Statehood, based on its crisis and the emerging forms of Earth’s “larger spaces” (Perulli 2014) in the current polycentrism of networked global city-regions. These have been interpreted as networks of relational contracts. Such contracts are both formal and informal, implicit (like the framework programmes between the EU, States, regions, cities and companies on subjects of knowledge, technologies, human capital etc.), incomplete and open to the future (like the multilevel and multiagent agreements on environmental goods and global commons). In all these contracts the State is only a contractor, in many cases we are dealing with relational contracts among urban actors (both government and functional), global networks and supranational governments. The State tries to have a voice in these contracts but its role is declining. For this reason the State, in order to maintain its political power, is now trying to recentralize when in the recent past it was required to decentralize. A theory of multilevel contracts would show the weakness of the State in: - new forms of governing the commons - new forms of cross-border economic networks - new forms of global polity (environment, human rights, immigration). These are signs of the post-national prospects that has opened, in which the role of “larger spaces” in formation (European Union first of all) could even be more important than that of the old Nation-States. REFERENCESAppadurai Arjun 1996, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press). Bagnasco Arnaldo 2010, Il Nord:una città-regione globale? in Perulli Paolo, Pichierri Angelo (eds.), cit. Brenner Neil 2004, New State Spaces (Oxford, Oxford University Press). Brenner Neil 2010, The ‘cityness’ of the city: what is the appropriate unit of analysis for comparative urban studies?, Lugano, Globalization of Urbanity, USI-Lugano, July. Brenner Neil, Madden David J., Wachsmuth David 2012, Assemblages, actor-networks, and the challenges of critical urban theory, in Brenner Neil, Marcuse Peter, Mayer Margit (eds.), Cities for People, not for Profit, (London-New York, Routledge). Calafati Antonio ,Veneri Paolo 2010, Re-defining the Boundaries of Major Italian Cities, Universita' Politecnica delle Marche, Economy Faculty, working paper n. 342, June. Cassese Sabino 2012, The Global Polity: Global Dimensions of Democracy and the Rule of Law,(Sevilla, Global Law Press/Editorial Derecho Global). Crestanello Paolo 2008, I processi di trasformazione dell’industria dell’abbigliamento veneto, “Economia e società regionale”, n. 1. Derudder Ben 2012, Milano digitale: posizione e potenziale nell’ambito del sistema urbano europeo, “Impresa§Stato”, n. 95. Grote Jurgen 2012, Horizontalism, Vertical Integration and Vertices in Governance Networks, “Stato e mercato”,n. 1, 94-103. Gualini Enrico 2003, The region of Milan, in Salet Willem, Thornley Andrew, Kreukels Anton (eds.), Metropolitan Governance and Spatial Planning, (London-New York, Spon Press). Latour Bruno 2005, Reassembling the social. An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory, (Oxford, Oxford University Press). Le Galés Patrick 2002, European Cities, (Oxford, Oxford University Press). Le Galés Patrick 2011, Governing cities, in Bridge G., Watson S. (eds.), Handbook of cities, (London, Sage). Nancy Jean-Luc 2002, La creation du monde ou la mondialisation, (Paris, Galilée). Perulli Paolo (ed.) 2014, Terra mobile. Atlante della società globale, (Turin, Einaudi). Perulli Paolo, Pichierri Angelo (eds.) 2010, La crisi italiana nel mondo globale. Economia e società del Nord, (Turin, Einaudi). Rodrik Dani 2004, Growth Strategies, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge (MA), August. Salet Willem, Thornley Andrew, Kreukels Anton (eds.) 2003, Metropolitan Governance and Spatial Planning, (London-New York, Spon Press). Sassen Saskia 2006, Territory, Authority and Rights, (Princeton, Princeton University Press). Scott Allen J. (ed.) 2001, Global City-Regions, (Oxford, Oxford University Press). Soja Edward 2000, Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions, Oxford, Basic Blackwell. Storper Michael, Scott Allen J. 2009, Rethinking human capital, creativity and urban growth, "Journal of Economic Geography”, vol. 9 (2). Storper Michael, Walker Richard 1989, The Capitalist Imperative. Territory, Technology and Industrial Growth, (New York, Basil Blackwell). Therborn Goran 2011, The World, (Cambridge, Polity). Tilly Charles 1992, Prisoners of the State, «International Social Science Journal», n. 133, Aug. Taylor Peter 2004, World city networks, (London-New York, Routledge). Tosi Simone, Vitale Tommaso 2011, Piccolo Nord. Scelte pubbliche e interessi private nell’Alto Milanese, Milano, B. Mondadori. NOTES* Paolo Perulli, University of Piemonte Orientale (IT) and Architecture Academy of Mendrisio (CH), email: paolo.perulli@uniupo.it 1. The etimology of the word ‘region’ among Indoeuropean institutions has been studied by Emile Benveniste and discussed by Pierre Bourdieu, according to the interpretations alluded to above. 2.Since 2004 China has overtaken Romania as the first supplier country of Northeast Italy industry (Crestanello 2008). 3.Tosi and Vitale (2011, p.23) points out that in the study of local communities “you cannot ignore studying the interaction taking place, local and translocal on multiple scales, with specific attention to the power relations which are formed”. 4. Storper and Scott (2009). 5. Taylor (2004).

|

||