GaWC Research Bulletin 455 |

|

|

|

This Research Bulletin has been published in Urban Studies, (2017), OnlineFirst. Please refer to the published version when quoting the paper

IntroductionOver the past three decades, globalization and capitalist restructuring have enabled a profound reorganization of spatial development processes. One major expression is the resurgence of cities as the organizational foundations of the new world economy (Castells, 1996; Friedmann, 1986; Sassen, 1991; Scott, 2012). The functional differentiations between major cities, the patterns of their inter-connections, and the characteristics of urban networks/hierarchies at different geographical scales have attracted extensive attention from urban researchers (Beaverstock et al., 2000; Derudder et al., 2010; Hall and Pain, 2006; Hoyler et al., 2008; Li and Phelps, 2016; Taylor and Derudder, 2016). Knowledge-intensive advanced producer services (APS), as a key driver of current globalization and an important builder of modern urban systems (Sassen, 1991; Castells, 1996), have become one of the most studied activities. However, research on urban networks generated by APS activities has focused either on the structures of the networks in general or on the patterns created by different service sectors. In comparison, whether advanced services originating from different regions (i.e., firms headquartered in different countries or regions) might generate different inter-city networks is less well studied. This paper fills that gap by exploring the diverse location strategies of 219 APS firms from different areas and their roles in creating multi-scalar urban networks based on the case of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) city-region in China (Figure 1). The key research question is how APS firms with headquarters either in the PRD itself, in mainland China, or overseas, impact the internal urban system and the external relations of the PRD through their business networks. The result is a detailed mapping of the multi-scalar APS-based urban networks of the PRD, which demonstrates the complex and variegated service geographies created by different types of services firms both within and outside China. In addition to this quantitative work, 21 in-depth interviews with actors working in APS firms and other related institutions in the study area were conducted to add valuable qualitative information. Figure 1. The geographical location of the Pearl River Delta

The paper is structured as follows. The next section briefly reviews the available research on inter-city networks in the modern knowledge economy and introduces our concerns. After that, the third section elaborates on the importance of the origin of firms in understanding their business strategies and geographical implications in specific institutional contexts, drawing on insights from national business systems and international business strategies research. The following two sections review the development of producer services in China and outline the methodological and data basis for our work. The sixth section describes and interprets the multiple inter-city networks of the PRD generated by different types of firms based on both the quantitative analysis and the interview information. The final section provides a conclusion of the study and discusses its implications. Inter-city networks in the modern knowledge economyIn contemporary urban studies, the world/global city has become a topic of focus. Many researchers try to understand the restructuring of major cities in the modern knowledge-intensive global economy as well as the various inter-urban networks they have formed. According to Castells (1989), the simultaneous processes of globalization and knowledge-intensification of economies have produced a ‘new spatial logic’ that is characterized by the pre-eminence of ‘space of flows’ over ‘space of places’. In this knowledge-economy-based ‘network society’, major world cities, instead of territorial nation-states, constitute the critical hubs of various ‘spaces of flows’. Friedmann (1986) defines world cities as the ‘major sites for the concentration and accumulation of international capital’ in the ‘new international division of labour’. Through looking at the ‘command and control’ functions of cities, he describes a transnational urban network with a hierarchical structure as the major geographical frame of the current capitalist world economy. Sassen (1991) further develops Friedmann’s world city theory but focuses on how the global control functions of cities are produced and practised. In her argument, it is the trans-nationalization of APS (e.g., finance, accountancy, legal services, advertising, etc.) firms and the simultaneous concentration of them in major cities that leads to the formation of the current transnational urban system. While Castells, Friedmann and Sassen have offered a conceptual framework for a networked understanding of cities in contemporary global economy, Taylor (2001, with Derudder, 2016) has provided an empirical instrument for systematically analysing inter-city relations through the lens of the organizational structure of APS firms. In his Interlocking Network Analysis, the office networks of a selection of ‘global’ APS firms are modelled to generate the world city network. Taylor and his colleagues from the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC)—a Loughborough University-based research network focusing upon research into the external relations of world cities—have conducted four rounds of data collection and analysis to date.1 Through comparing outcomes from different years, they have discovered a gradual shift of global service centres from the ‘West’ to the ‘East’, that is, a decline in the connectivity of US cities and an increase in the Asian, especially Chinese, cities in the global services economy (Derudder et al., 2010). Taylor’s work has triggered many follow-ups on the APS-based inter-city networks at the global (Derudder et al., 2010; Hanssens et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b), the national (Derudder et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2015; Zhen et al., 2013) and the regional (Hall and Pain, 2006; Hanssens et al., 2014; Hoyler et al., 2008; Lühti et al., 2010; Zhang and Kloosterman, 2016) scales. Despite their richness in terms of area and sector, there is little information on the location strategies of firms from different geographical areas and their roles in the formation of urban networks. On the one hand, since the current global advanced service economy is largely dominated by a number of international service providers from the Western developed world, scholars focusing on the inter-city networks at global or national scales tend to select their observations from leading (Western) international APS firms rather than from national and regional ones. On the other hand, although some studies on the service networks at the city-regional scale (Hoyler et al., 2008; Lühti et al., 2010; Zhang and Kloosterman, 2016) have used firms ranging from small local operators to large multinationals, they have not made a clear distinction between the networks created by different firms, which has limited their contribution to our understanding of the diverse service geographies of firms with different origins. Firm origins, host country contexts and business strategiesThe influence of firms’ country of origin on their business activities and performance has been extensively explored by national business systems research. A common finding is that the features of the market conditions, business systems and institutional environments in the home countries (or regions) of firms tend to influence a wide range of their organizational and strategic characteristics (North, 1990; Pauly and Reich, 1997; Whitley, 1999). Firms build their strategies and structures through engaging with the particular ‘economic’ rules of the game embedded in their home region’s institutional and cultural contexts, which give them particular capabilities and competitive advantages (Morgan, 2007). These distinct institutional and cultural legacies continue to significantly shape the core operations of firms even after they enter another national or regional context. As such, even in a world with increasing globalization, transnational corporations continue to diverge fairly systemically in both their internal organizational structures and their overseas investment strategies (Mayrhofer, 2004; Pauly and Reich, 1997). Such divergence, through directing the market and investment choices of firms, further influences the interaction of firms with the host economy (Fortanier, 2007). The national business systems framework highlights the significance of firms’ origin in understanding their international strategies and growth impacts. This is of particular importance in the current transitional era. With the restructuring of the world economy and the shift of global economic power eastwards, a growing number of firms from newly emerged economies (e.g., China) will have a strong intention to extend businesses beyond their domestic markets into the international arena. It can be expected that the behaviour of these firms may not fully comply with that of the currently dominant ‘global’ players from the developed world but reflects the specific commercial, institutional and cultural traditions of their home regions (c.f. Peng et al., 2008). For example, in their latest work, Taylor et al. (2013) have observed ‘a very distinctive servicing geography’—¬the ‘China strategy’¬—with its own regional concentration and worldwide distribution of firms in formation. They speculate that this unique servicing geography may ‘reflect Chinese overseas past, present and possible future investments’, and could possibly become a new type of intervention in the world city network. These distinct business strategies, location choices and growth impacts (e.g., the formation of inter-city networks) of firms from emerging economies deserve more concern from researchers. In addition, at the national or regional scale, the impact of firms’ origin on their development implications is further complicated by the diverse institutional contexts in host economies. Many countries (and regions) tend to treat domestic and foreign firms differently, and formulate discriminative laws, regulations and investment policies according to firms’ origins and ownerships. These formal institutional arrangements, together with other informal institutions such as norms governing interpersonal relationships, constitute a key context of competition among industries and firms (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Wright et al., 2005). As a consequence, the strategies adopted by firms after entering a market tend to be shaped jointly by the specific resources and capabilities of the firms, the nature of the industry they belong to, and, importantly, the formal and informal institutional environment in the host economies (Peng, 2006). Institutional peculiarities affect both a location’s attractiveness to foreign investors and the preferred entry mode adopted by these investors (Bevan et al., 2004; Meyer and Nguyen, 2005). Geographically, through directly or indirectly influencing investment strategies and operational behaviours of firms, the local institutional context may affect the contribution of firms to the formation of regional economic spaces. For instance, discriminated state regulation of foreign firms and long-term informal relations with local customers may bring native firms many advantages in competing with their foreign counterparts. Therefore, although they possess superior financial resources and marketing capacities, transnational firms may face many constraints in selecting clients, businesses and locations in a host country, which limits the role they can play in regional economic development. This implies that while the formation of the current world city network is mainly driven by some key ‘global’ players from the developed world, at lower scales, urban or regional development can be promoted by more diverse actors and forces. Such diversity also deserves further investigation from a geographical perspective. In this paper, we probe these two issues through investigating the location strategies of APS firms with different origins and the multi-scalar inter-city networks they have created within and beyond China’s PRD city-region. As a transitional economy, China has many institutional differences compared to Western developed economies (Lin, 2005), including the complicated, even opaque, state-market relationship (Jacques, 2012). This unique context makes it an interesting case to explore the complex relationship between the origins of firms, the host country’s institutional environment, and spatial development processes. In addition, unlike most European countries, China’s national economic landscape is not dominated by any city or region but is constituted by a large number of cities and regions at different levels of development. Such diversity enables us to further compare the geographical impacts of different Chinese firms in specific regional contexts. Therefore, in the following analysis we distinguish not only between Chinese and foreign firms but also between Chinese large national firms and small local ones, to explore the diverse inter-city networks created by them. To begin, we will briefly review the development of producer services in China. The Development of Producer Services in ChinaProducer services normally refer to ‘intermediate-demand (as opposed to final-demand) services that represent inputs into the production process of firms and other organizations’ (Coffey, 2000: 171). In China, the development of producer services is a relatively new phenomenon. During the centrally planned economic period (1949-1978), due to the anti-market and anti-consumption ideology as well as the dominance of the state in allocating resources and organizing production, demand for services was minimized across the country. Most producer service activities were internalized into individual state agencies and state-owned enterprises and were severely suppressed in the harsh economic and political environment (Yang and Yeh, 2013; Yeh and Yang, 2013: 10). This situation lasted until the Chinese central government initiated the ‘economic reform and opening-up’ programme. Since the late 1970s, the introduction of market mechanisms has gradually removed many obstacles for the development of services. Meanwhile, the fast-growing domestic economy has generated an increasing demand for services. As a result, service sectors experienced dramatic growth in China. From 1978 to 2009, the share of services in national GDP and employment increased from 23 percent and 12 percent to 43 percent and 34 percent, respectively (Yeh and Yang, 2013: 10). Producer services started to expand rapidly after the 1990s. Between 1990 and 2006, the annual growth rate of output value of producer services reached 19 percent (Yeh and Yang, 2013: 4). It is estimated that by 2008, 1.16 million producer service establishments were operating in China, creating 34.4 million jobs. The contributions of producer services to the national economy amount to 16.4 percent in terms of the number of establishments and 12.7 percent in terms of employment (Yang and Yeh, 2013). Meanwhile, China also gradually opened its service sectors to foreign investors, especially after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. By 2012, China’s import and export of services reached 280 billion and 190 billion USD, respectively, making it the third largest importer and the fifth largest exporter of services in the world. Foreign investment in services increased to 53.8 billion USD, accounting for 48.2 percent of the gross foreign investment in the country (MoC, 2013). Many global leading producer services firms have set up their branches or representative offices in mainland China. Some Chinese service firms, especially in the financial sector, have also grown into giant producer service providers according to the international standard. However, it is worth noting that the Chinese service market is still far from an open, competitive market. State regulation and intervention are still pervasive and tend to treat domestic and foreign firms differently in many sectors. Service activities that are deemed as lifelines of the national economy (e.g., finance) or are related to state sovereignty (e.g., law) are still highly regulated (in some cases, even tightly controlled) by the government. Therefore, producer services provide a strategic window to understand some key aspects of the structural transitions of China’s economy, i.e., the degree of openness, the state-market relations, the interactions between institutions and economic activities, etc. In the remainder of this paper, we probe into some of these questions in detail based on the evidence from the PRD. Data and MethodsIn this paper, we use Interlocking Network Analysis to map and evaluate the inter-city networks generated by APS firms within and beyond the PRD. This method was initially developed by Taylor (2001) to systematically analyse inter-city relations at the global scale, and then was extended by Hall and Pain (2006) to explore similar relations at the mega-regional scale. Its basic idea is as follows: APS firms, as a major driver of contemporary economic development and globalization, have created worldwide, city-centred office networks to provide specialized services to their global customers (Sassen, 1991). Each of these office networks is the outcome of an APS firm’s long-term location strategy that reflects its consideration of the investment conditions and potential values of different places. Cities in such a network can be linked with each other through the communication of information, knowledge, ideas and people between different offices, constituting part of what Castells (1996) calls the ‘space of flows’. Therefore, a close examination of the office networks of a large number of APS firms can provide a surrogate measure of the knowledge-based service connections between cities where these offices are located as well as the importance of each city within the regional/national/global service networks. A detailed explanation of this method can be found in Taylor (2001) and Taylor et al. (2008). Due to space limitations, here we only describe the data collection and analysis processes, focusing on our modifications to make the method more compatible for the current purpose. Selecting FirmsThis paper selected five APS sectors for analysis: banking, insurance, accountancy, law and advertising. There were two criteria for selecting firms: the firm should have offices in at least two cities (multi-location firms), and at least one of its offices should be in the PRD. Different to the GaWC’s work, which only focused on leading international firms, this study’s database contained firms varying from large international service providers to small local operators. The sets of firms were different according to the scale (global, national, regional) in analysis, because some firms only had offices within the PRD while others also had offices in other cities in mainland China or abroad. Firms were identified from different sources, including statistical yearbooks (e.g., the Law Yearbook of China and the Almanac of China’s Finance and Banking), reports from specialized associations (e.g., reports from the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants and the Association of Accredited Advertising Agencies of China), and business rankings (e.g., rankings provided by the Asian Legal Business magazine). The lists of firms from different sources were crosschecked to ensure that the most important firms were included. Information about the location and function of the offices was collected mainly from the official websites of the firms and supplemented by some specialist statistical websites and other Internet sources. Firms with no information available were excluded. In the banking and insurance sectors, all firms that met the two criteria were selected into our database since only a limited number of banks and insurance firms were operating in the PRD. In the sectors of law, accountancy and advertising, we selected from higher-ranked firms to lower-ranked firms until we could identify no additional multi-location firms. The final database comprised 219 APS firms (Table 1). It is reasonable to believe that this database contained most important multi-location firms in the five sectors in the PRD. Table 1. Distribution of firms' headquarters

Notes: a) Two advertising firms have dual headquarters in both New York and London Selecting CitiesTo make data collection and analysis feasible, a limited number of cities were selected at the regional (PRD), national (mainland China) and global scales. Regionally, all nine cities within the PRD were selected (Figure 1).2 National cities were chosen according to their administrative function (i.e., provincial capital) and economic performance (i.e., GDP) in the national urban system. The selection of global cities was primarily based on the GaWC world city index 2008 (all ALPHA and BETA cities) and complemented by some extra cities that were identified as important during data collection. We treated Hong Kong and Macao as two global cities because of the different political and administrative environments between them and mainland China.3 In addition, most international firms also chose to list these two cities and mainland China as two separate markets on their websites. Together, 9 regional cities, 43 national cities and 95 global cities constituted the city set. Creating the Service Value MatrixTo make different firms comparable, each city was allocated a service value that indicated the importance of this city in a firm’s business network. Service values should be allocated on a unified scale. The GaWC used a 6 grades system (from 0, which indicates no office, to 5, which indicates headquarters) to study the world city network. A single valuing system is less problematic when firms are similar in size (e.g., when all of them are large international firms). However, since this paper used firms ranging from small local operators to large international ones, it was necessary to take this diversity into consideration. The strategy we used was to set a maximum service value for each firm according to the number of its location cities (i.e., firm size), ranging from 3 (headquarter city of a firm located in less than 20 cities) to 5 (headquarter city of a firm located in more than 40 cities). All cities with a firm’s presence were initially allocated a standard service value of 2, while cities with no office were scored as 0. Then, a city’s service value might be lowered to 1 or be raised to 3, 4 or 5 according to the size and/or function of its office(s). It was relatively easy to identify headquarters and the absence of an office. However, the identification of higher or lower level offices proved more difficult due to the limitation of information. This might lead to a more subjective valuation for some cities. According to Liu and Taylor (2011), subjective uncertainty in determining the service values would not create significant rank shifts for higher-ranked cities but may affect lower-ranked ones. Therefore, following their suggestion, we grouped cities into tiers of similar connectivities when interpreting results. The connectivity between two cities i and j (Ci-j) is calculated as: Ci-j =ΣVi,f·Vj,f (where Vi,f is the ‘service value’ of city i to firm f, and i≠j). This provides a measurement of the potential connections (work flows, transfers of information and knowledge) between city i and city j. The assumption is that the more important the office (Vi,f), the more links there will be with other offices (Vj,f) in a firm’s network. The gross connectivity of a city (GC), indicating a city’s overall importance within the network, is calculated as: GCi =ΣCi-j (where i≠j). Firms with headquarters in the PRD, outside the PRD but in mainland China, and outside mainland China were analysed separately. For each category of firms, the inter-city connectivities and gross connectivities were also calculated at three (regional, national and global) different geographical scales. This created nine matrices of inter-city connections. The outcomes were visualized using GIS technology. In addition, 21 interviews (respectively, 15 with senior managers of APS firms, 1 with a representative of a foreign chamber of commerce, 2 with service industrial associations and 3 with experts) were conducted in Guangzhou and Shenzhen between May and July 2013. All but four firms were selected from the quantitative database. We first selected a number of firms of different sizes and origins from each sector in the database and contacted them through telephone or e-mail. Then, we conducted interviews with those firms who accepted our request. The main questions included the following: what services are provided by their office(s) in the PRD, who the main customers are and where they are located, why they chose a specific city (or cities) in the PRD as their regional headquarter or branch(es), how different offices of their firms cooperate and communicate, and what factors may affect the development of their firm and where they may choose to expand businesses. Each interview was undertaken in a semi-structured way and lasted for approximately one hour. This first-hand information is used to explain the outcomes of the quantitative analysis. The multiple geographies of knowledge-intensive service networks of the Pearl River DeltaFirms and ConnectivitiesAmong the 219 APS firms in the database, only a small number (30, or less than 14 percent) have their headquarters in the PRD (named the ‘PRD firms’ hereafter), and all of them are located in either Guangzhou (leading in law and advertising) or Shenzhen (leading in insurance) with only two exceptions—one bank in Dongguan and one law firm in Foshan (Table 1). Approximately half (104) of the firms originate from other cities in mainland China (named the ‘National firms’ hereafter) and most (66) are concentrated in the national capital, Beijing. Shanghai’s underperformance in headquarter function is somewhat unexpected given its great economic importance and global financial centre status. Although it has the second largest number (13) of headquarters among all national cities, the number is much lower than that in Beijing (66). Other headquarters of the ‘National firms’ are spread across a number of major regional political and economic centres in China. There are 85 (39 per cent) firms headquartered outside mainland China (named the ‘Overseas firms’ hereafter) with nearly two-thirds concentrated in three cities—London, New York and Hong Kong. It is interesting to note the division of sectors between these three cities, with London leading in accountancy, New York in advertising and Hong Kong in legal services. Tokyo also hosts a number of headquarters in the sectors of banking, insurance and advertising. We can also observe that, compared to their western counterparts, Asian firms (firms with their headquarters in Asian cities) tend to be concentrated in the financial sectors (banking and insurance). The aggregate analysis of the multi-scalar network connectivities of the PRD reveals that three categories of firms function diversely in the creation of service networks at different scales (Table 2). The ‘National firms’ are the most important contributor to the PRD’s internal networks and, in particular, to its connections with other Chinese cities. Nearly 60 percent of the PRD’s regional connectivities and more than 70 percent of its national connectivities are created by these firms. The ‘PRD firms’ account for nearly 30 percent of the region’s internal connectivities, which is quite remarkable compared to their small number. However, their significance declines sharply at the national scale and almost vanishes at the global scale. The functioning of the ‘Overseas firms’ is very modest at the regional and national scales. However, they are the main agents in linking the PRD with the global service networks. Over 90 percent of the PRD’s global connectivities are created by firms with overseas origins. Table 2. Firms’ contributions to the multi-scalar network connectivities of the Pearl River Delta Unit: %

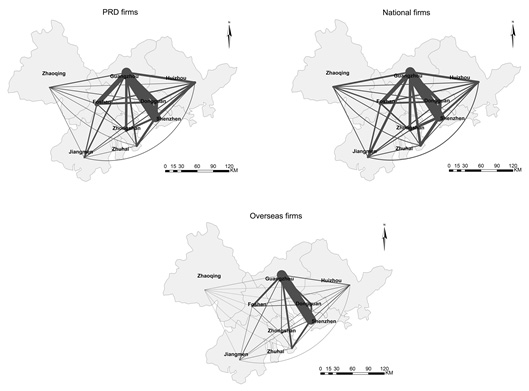

The differences among firms also exist in their spatial distributions within the region. Figure 2 shows the relative importance of individual cities in the multi-scalar networks created by firms from different areas. Clearly, the ‘Overseas firms’ tend to provide services mainly in two core cities—the regional administrative centre Guangzhou and the SEZ Shenzhen—while the ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms have more polycentric business networks (Figure 3). According to the interviewees, this divergence arises from two related factors. First, the clients of the ‘Overseas’ APS firms in the PRD are mainly foreign and Chinese large corporate customers (and some ‘high-level’ individual customers). Their offices in the region have a strong tendency to follow the headquarter functions of their major customers, who basically concentrate in either Guangzhou or Shenzhen. The ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms, in comparison, have more diverse customers varying from big companies to small entrepreneurs (and individuals as well) whose locations are spread within the region. Therefore, they need more extensive office networks to cater to the demand of these local clients. Figure 2. Multi-scalar network connectivities of cities in the Pearl River Delta according to firms with different origins

Figure 3. Regional connections of the Pearl River Delta according to firms with different origins

Second, based on their institutional advantages in the domestic market brought by the unequal state regulations governing Chinese and foreign firms and their local embeddedness formed historically, those Chinese large APS firms (e.g., banks and insurance firms) have more formal and informal resources to maintain a large number of offices and provide services to customers at a broader geographical scale. It is very costly for foreign firms to build similar networks and compete with existing Chinese firms after they enter the region, which forces them to adopt differentiated marketing and location strategies. As one interviewee from a foreign bank explains,

Another interviewee notes that one major reason for them to ‘locate mainly in the first-tier cities’ is ‘because the policy environment in the second- or third-tier cities is more beneficial for domestic banks’.

As a result, networks created by the ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms are more polycentric and finely grained than those of the ‘Overseas’ firms in the PRD. Although our database only contains those major multi-location APS firms in the PRD, excluding hundreds, maybe even thousands, of small, single-office local firms, the above outcome still provides some interesting insights. First, high-end service activities have a tendency to concentrate at different geographical scales (cf. Daniels, 1991; Coffey, 2000). The headquarter functions of APS firms are highly concentrated in several core cities at the global, national and regional scales. Such a concentration probably will consolidate the economic dominance of major cities and exacerbate spatial inequality with the expansion of advanced services. Second, there is a simultaneous development of regional, national and international service operators in the PRD. Local firms only occupy a small part of the leading APS operators in the region, overshadowed by firms with headquarters in other Chinese (particularly Beijing and Shanghai) and overseas cities. This is in part attributed to the PRD’s former development trajectory in the 1980s and early 1990s, which focused on low-end, small-scale manufacturing production (Yang, 2012) and ‘could not provide sufficient demand for the internal growth of high-end producer services in the region’ (information provided by a director from an advertising association, 23 May 2013). Third, while Chinese APS firms in general have a very limited presence in the global arena, they dominate the producer service market and networks within mainland China, even in one of its most opened areas. On the one hand, this reflects the relatively short development period and low-level internationalization of China’s producer service sectors. On the other hand, it confirms that many parts of the country’s service market are still not freely accessible for foreign actors. Profiles of External ConnectionsNational connections. The mapping of the national connections reveals the dominance of Beijing and Shanghai in the networks created by all three categories of APS firms (Figure 4). Due to their unique positions and ‘qualitatively different roles’ in China’s economic and political landscapes, that is, Beijing as the capital and the location of the headquarters of most Chinese SOEs and Shanghai as a world financial centre and the location of the Chinese headquarters of most international companies (Lai, 2012), these two gateway cities are not only the birthplace of most leading Chinese APS firms but also the first choice for foreign firms to enter mainland China (information provided by several senior managers from APS firms). Notably, although Shanghai has many fewer headquarters than Beijing (Table 1), it only lags slightly behind Beijing in the ‘National’ firms’ networks and even surpasses the latter in the ‘PRD’ and the ‘Overseas’ firms’ networks. This is because many Chinese APS firms, although having headquarters somewhere else, tend to set up a sub-headquarter or major office in Shanghai; for foreign firms, Shanghai is a slightly more attractive location than Beijing for their headquarters or branches in mainland China. Both Chinese and foreign APS firms are attracted to Shanghai’s financial resources (e.g., the Stock Exchange and the Foreign Exchange Trading Centre), market diversity and more internationalized business environment. For foreign firms, the concentration of a large number of transnational company headquarters is also an important reason for them to choose Shanghai (information provided by several senior managers from APS firms). Figure 4. National connections of the Pearl River Delta according to firms with different origins

We can also observe some differences between the national networks created by firms from different areas. The ‘Overseas’ firms have more centralized networks in China. They are highly concentrated in Shanghai and Beijing and, to some extent, prefer cities in the eastern coastal area and the Chengdu-Chongqing region. Apart from their economic prosperity and higher degree of openness, China’s special business and institutional environment is also an important reason for ‘Overseas’ firms to concentrate in these cities. Compared with their foreign counterparts, Chinese APS firms (especially government-backed ones) still have great advantages in cooperating with the national and/or local government, building tight, long-term (sometimes informal) relationships with Chinese clients, and accessing information and resources through inter-personal connections. These advantages are even ‘more prominent in the interior regions and smaller urban areas’, where ‘the development of the market still lags behind the more open metropolitan areas’; therefore, non-market factors (such as ‘inter-personal relations’) tend to play a greater role. As such, most foreign APS investors prefer coastal cities and large metropolises, which have a ‘relatively more transparent market’, a ‘less bureaucratic administrative system’, a ‘large labour pool’ and a ‘concentration of headquarters of international companies’, as the locations for operating in the Chinese market (information provided by several interviewees from foreign APS firms in Guangzhou and Shenzhen). In comparison, in the networks of the ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms, cities at a higher political level, i.e., provincial capitals (Chengdu, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Nanjing, etc.), are relatively better connected, which is arguably related to their administrative functions within China’s centralized bureaucratic system. In addition, for the ‘PRD’ firms, although Shanghai and Beijing are still the best-connected cities, the gap between them and other national cities is not as large as in the ‘National’ and the ‘Overseas’ firms networks. The explanation lies in the intense competition in these two cities. Since Beijing and Shanghai are already two leading service centres and homes to many large APS firms, it is relatively difficult for firms from other regions in China to set up branches in these two cities and compete with local firms. Therefore, although Beijing and Shanghai have the best resources and market opportunities for APS activities, firms from other regions normally do not choose to set up branches in these two cities. Instead, they prefer Chinese cities that are fast growing but with less-intensive competition (e.g., Changsha, Ningbo, Dalian, Shenyang, Zhengzhou, etc.) as the first place to extend businesses (information provided by interviewees from some ‘PRD’ APS firms). Here, we can observe a clear hierarchy within China’s urban system and an asymmetry of influence between the core cities (particularly Beijing and Shanghai) and others. Global connections. Several interesting patterns can be observed in the global service connections of the PRD (Table 3). First, the ‘PRD firms’ have very few overseas connections (in only six cities), and most of them are concentrated in Hong Kong. Considering the geographical proximity and socio-cultural similarity, it is not hard to understand that most APS firms in the PRD will choose Hong Kong as the first place to extend their businesses overseas. It also reflects the legacy of the ‘front office-back factory’ type of development between Hong Kong and the PRD in the 1980s and 1990s (Sit and Yang, 1997). Other connected overseas cities in the ‘PRD’ firms’ networks include Macao, another geographically adjacent but institutionally different city; New York and London, two leading global financial and service centres; Taipei, an important source of FDI in the PRD; and Montevideo. These cities have only one or two linkages with the PRD. Therefore, they reflect the choices of a few pioneer firms. Table 3. Top 20 connected global cities according to firms with different origins

Note: Values are calculated as proportions of the value of the best connected city. Second, geographical and cultural proximity also matters in the ‘National’ firms’ overseas location strategies. Hong Kong, once again, stands out with a substantial lead in the overseas networks created by these firms. Only a very few ‘National’ firms do not choose Hong Kong as the first springboard to go outside. In addition, nearly half of the top 20 connected global cities (e.g., Singapore, Tokyo, Macao, Seoul, Jakarta) are from East and Southeast Asia, reflecting China’s intensive connections with these geographically nearby areas. However, the absence of Taipei from the top 20 is rather unexpected. An important reason could be that in Taiwan there are some investment restrictions on financial firms from mainland China (information provided by a senior counsellor from a bank in Guangzhou, 16 July, 2013). Other relatively well-connected cities are the leading global financial centres, such as New York, London, Frankfurt, Sydney and, particularly, Luxembourg. This is not surprising since the largest and most influential Chinese APS firms concentrate in the financial sector. Rotterdam’s high value should be related to its function as a major port in Europe. In general, the global reach of Chinese APS firms is still rather limited. One reason is because most Chinese APS firms have a relatively short development history. Most of them were established in the past two or three decades. Therefore, they have very limited resources and capabilities to compete with their large western counterparts in the international market. Other factors that hinder the globalization of Chinese APS firms are the ‘different game rules, ‘cultural and institutional barriers’, and even some ‘political constraints’4 in foreign markets (information provided by several senior managers and counsellors from some Chinese APS firms). Due to these institutional barriers, as well as the growing domestic demand, most Chinese APS firms still prefer to concentrate their businesses at home. Finally, the networks created by the ‘Overseas firms’ are more widespread in geography at the global scale. The ranking of cities is flatter, with London as the best-connected city followed closely by Hong Kong, New York and Singapore. All of the top 20 connected cities are ‘Alpha’ world cities in the GaWC world cities list, or, in other words, ‘centres that link major economic regions and states into the world economy’. In comparison, the influence of special factors such as geography (e.g., Macao, Ho Chi Minh City) is less important as for the networks of Chinese firms. Apparently, the leading international APS operators have developed more mature global business networks that rely on main regional centres to provide services for different areas. The global strategies of different types of firms reflect both their developmental histories and the economic and geo-cultural connections of their home countries/regions. ConclusionsIn this paper, we attempt to capture some new patterns of China’s economic transition and urbanization in the emerging knowledge-intensive service economy based on a case study of the PRD. Our main finding is that the formation of APS-based urban networks at different geographical scales is partly determined by the origins of firms. While cities in the PRD are connected with each other and with other Chinese cities primarily through local and national business networks of the APS firms, the region’s linkages with overseas service centres have been shaped predominantly by those major international APS firms from the advanced economic world. This pattern reflects a simultaneous development of regional, national and international service operators in China. Moreover, different types of firms have created quite diverse service geographies at different spatial scales. Within the PRD, the ‘Overseas’ firms rely heavily on the two core cities- Guangzhou and Shenzhen- to provide services, while the ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms have created more extended service networks. At the national scale, the ‘Overseas’ firms also have more centralized service networks and prefer open coastal cities and large metropolises. In comparison, in the networks of the ‘National’ and the ‘PRD’ firms, cities at a higher political level are more privileged. At the global scale, the Chinese APS firms have a relatively limited global reach. Geographical and cultural proximity tend to be an important consideration in their overseas location choices. The international APS firms, by contrast, have developed more mature global business networks and mainly use regional hub cities to provide services for different areas. The patterns of the nested city-service network of the PRD certainly reflect different firms’ development histories, their client orientations in specific markets and their home regions’ economic conditions. However, they are also significantly shaped by China’s unique regulatory environment and complex state-market relations. Different from the bottom-up, foreign investment-triggered and export-oriented industrialization in the 1980s and early 1990s (Yang, 2012), the development of modern service economies in China has been driven mainly by domestic demand under tight state regulation and government guidance at the outset. It left for a long time very limited space and opportunity for foreign capital and actors to participate. In the meantime, the huge domestic demand, along with the different commercial and institutional environment between the domestic and the international market, also became an obstacle that hindered Chinese APS firms from going out and extending businesses at the global scale. Therefore, due to diverse regulatory and institutional contexts, the formation of the APS-based inter-city networks at lower scales is more complex than the current research on world city networks has revealed. To properly understand this complexity, a scale- and actor-sensitive perspective is needed. This paper improves our understanding of the complex relations between firm origins, their business strategies and location choices within different institutional contexts, and their regional growth impacts in the new service economy. On the one hand, the paper reveals that APS firms originating from emerging economies such as China demonstrate many different features in location choices compared to their counterparts from the developed world, which have the potential to bring ‘a possible new intervention’ to the global service economy and world city network (Taylor et al., 2013) in the future. However, as the findings also show, currently the degree of internationalization of such emerging firms and their capability to link cities and regions in their home country/region with the global service economy are still quite limited. This is due to both firm-specific reasons and the cultural-institutional differences between the Chinese and the foreign markets. We can note that most Chinese APS firms with overseas branches (especially in the financial sector) are either state-owned or state-sponsored, whose main function is to provide services for Chinese companies and individuals operating or living in foreign countries. The internationalization of China’s APS sectors relies on the globalization of the country’s domestic economy in general. On the other hand, institutional barriers also create a ‘safe zone’ for domestic firms in their home region, which generates profound economic and spatial implications. According to our study, although many formal restrictions on foreign operators have been (or are being) removed, Chinese APS firms (especially government-backed ones) still enjoy great institutional advantages compared to their foreign counterparts in the domestic market. This forces many foreign firms to either adopt different market strategies (e.g., serving different clients and/or drawing on different capabilities) or to cooperate with local Chinese firms. Spatially, this institutional environment tends to facilitate the agglomeration tendencies of high-end economic activities in major cities and regions in the country, potentially consolidating China’s current hierarchical urban system as a result. This new spatial uneven development accompanied with the rise of advanced service economies deserves more in-depth exploration. REFERENCESBeaverstock, J.V., Smith, R.G. and Taylor, P.J. (2000) World-city network: a new metageography? Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(1), pp.123-134. Bevan, A., Estrin, S. and Meyer, K. (2004) Foreign investment location and institutional development in transition economies. International Business Review, 13(1), pp.43-64. Castells, M. (1989) The Informational City: Information Technology, Economic Restructuring, and the Urban-Regional Process, Oxford: Blackwell. Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Coffey, W.J. (2000) The geographies of producer services, Urban Geography, 21(2), pp.170-183. Daniels, P.W. (1991) Services and Metropolitan Development, London and New York: Routledge. Derudder, B., Taylor, P.J., Ni, P. et al. (2010) Pathways of Change: Shifting Connectivities in the World City Network, 2000-08, Urban Studies, 47(9), pp.1861-1877. Derudder, B., Taylor, P.J., Hoyler, M. et al. (2013) Measurement and interpretation of connectivity of Chinese cities in world city network, 2010, Chinese Geographical Science, 23(3), pp.261-273. Fortanier, F. (2007) Foreign direct investment and host country economic growth: Does the investor’s country of origin play a role. Transnational Corporations, 16(2), pp.41-76. FORTUNE (2013) Global 500, URL: http://fortune.com/global500/2013/. Friedmann, J. (1986) The world city hypothesis, Development and change, 17(1), pp.69-83. Hall, P. and Pain, K. (eds) (2006) The Polycentric Metropolis: Learning from Mega-City Regions in Europe, London: Earthscan. Hanssens, H., Derudder, B., Taylor, P.J. et al. (2011) The changing geography of globalized service provision, 2000-2008, The Service Industries Journal, 31(14), pp. 2293-2307. Hanssens, H., Derudder, B., Van Aelst, S. et al. (2014) Assessing the functional polycentricity of the mega-city-region of Central Belgium based on advanced producer service transaction links, Regional Studies, 48(12), pp.1-15. Hoskisson, R.E., Eden, L., Lau, C.M., et al. (2000) Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): pp.249-267. Hoyler, M., Freytag, T. and Mager C. (2008) Connecting Rhine-Main: the production of multi-scalar polycentricities through knowledge-intensive business services, Regional Studies, 42(8), pp.1095-1111. Jacques, M. (2012) When China Rules the World (2nd edn), London: Penguin Books. Lai, K. (2012) Differentiated markets: Shanghai, Beijing and Hong Kong in China’s financial centre network, Urban Studies, 49(6), pp. 1275-1296. Li, Y. and Phelps N. (2016) Megalopolis unbound: Knowledge collaboration and functional polycentricity within and beyond the Yangtze River Delta Region in China, 2014. Urban Studies, published online before print, doi: 10.1177/0042098016656971. Lin, G.C.S. (2005) Service industries and transformation of city-regions in globalizing China: new testing ground for theoretical reconstruction, in Daniels, P.W., Ho, K.C. and Hutton, T.A. (eds) Service Industries and Asia-Pacific Cities: New Development Trajectories, London and New York: Routledge, pp.283-300. Liu, X., Neal, Z. and Derudder, B. (2012) City networks in the United States: a comparison of four models, Environment and Planning A, 44(2), pp.255-256. Liu, X. and Taylor P.J. (2011) Research note- a robustness assessment of global city network connectivity rankings, Urban Geography, 32 (8), pp.1227-1237. Lüthi, S., Thierstein, A. and Goebel, V. (2010) Intra-firm and extra-firm linkages in the knowledge economy: the case of the emerging mega-city region of Munich, Global Networks, 10(1), pp.114-37. Mayrhofer, U. (2004) International market entry: does the home country affect entry-mode decisions?. Journal of International Marketing, 12(4), pp.71-96. Meyer, K.E. and Nguyen, H.V. (2005) Foreign investment strategies and sub-national institutions in emerging markets: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of management studies, 42(1), pp.63-93. MoC (Ministry of Commerce) (2013) The Ministry of Commerce’s regular press conference, 16 January 2013, URL: http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/i/jyjl/m/201301/20130100005067.shtml (in Chinese). Morgan, K. (2007) The learning region: institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, 41(S1), pp.S147-S159. North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Pauly, L.W. and Reich, S. (1997) National structures and multinational corporate behavior: enduring differences in the age of globalization. International Organization, 51(1), pp.1-30. Peng, M.W. (2006) Global Strategy. Cincinnati: South-Western Thomson. Peng, M.W., Wang, D.Y. and Jiang, Y. (2008) An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of international business studies, 39(5), pp.920-936. Sassen, S. (1991) The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Scott, A.J. (2012) A World in Emergence: Cities and Regions in the 21st Century, Cheltenham and New York: Edward Elgar. Sit, V.F.S. and Yang, C. (1997) Foreign-investment-induced exo-urbanisation in the Pearl River Delta, China, Urban Studies, 34(4), pp.647-677. Taylor, P.J. (2001) Specification of the world city network, Geographical Analysis, 33, pp.181-194. Taylor, P.J. and Derudder, B. (2016) World City Network: A Global Urban Analysis (2nd). London: Routledge. Taylor, P.J., Evans, D.M. and Pain, K. (2008) Application of the interlocking network model to mega-city regions: measuring polycentricity within and beyond city-regions, Regional Studies, 42(8), pp.1079-1093. Taylor, P.J., Derudder, B., Hoyler, M. et al. (2013) New regional geographies of the world as practised by leading advanced producer service firms in 2010, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), pp.497-511. Taylor P., Derudder B., Hoyler M., et al. (2014a) City-dyad analyses of China’s integration into the world city network, Urban Studies, 51(5), pp. 868–882. Taylor, P.J., Derudder B., Faulconbridge, J., et al. (2014b) Advanced producer service firms as strategic networks, global cities as strategic places, Economic Geography, 90(3), pp.267-291. Whitley, R. (1999) Divergent Capitalisms: The Social Structuring and Change of Business Systems: The Social Structuring and Change of Business Systems, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., Hoskisson, R.E. et al. (2005) Guest editor’s introduction: Strategy research in emerging economies: challenging the conventional wisdom. Journal of Management Studies, 42(1), pp.1–33. Yang, C. (2012) Restructuring the export-oriented industrialization in the Pearl River Delta, China: institutional evolution and emerging tension, Applied Geography, 32(1), pp.143-157. Yang, F.F. and Yeh, A.G. (2013) Spatial development of producer services in the Chinese urban system, Environment and Planning A, 45(1), pp.159-179. Yeh, A.G. and Yang, F.F. (eds.) (2013) Producer Services in China: Economic and Urban Development, London: Routledge. Zhang, X. and Kloosterman, R.C. (2016) Connecting the ‘workshop of the world’: intra- and extra-service networks of the Pearl River Delta city-region, Regional Studies, 50(6), pp.1069-1081. Zhao M., Liu X., Derudder B., et al. (2015) Mapping producer services networks in mainland Chinese cities, Urban Studies, 52(16), pp.3018-3034. Zhen, F., Wang, X., Yin, J. et al. (2013) An empirical study on Chinese city network pattern based on producer services. Chinese Geographical Science, pp.1-12.

NOTES* Xu Zhang, Department of Regional Planning and Management, Wuhan University of Technology, China (email: x.zhang86@hotmail.com) 1. More information about the GaWC is available at http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/. 2. Since most statistics and maps are available at the prefecture level, we use municipality as the basic unit for collecting and organizing data. 3. For instance, HK banks and law firms are regulated as foreign banks and law firms by the Chinese government. 4. For example, one senior manager from a bank mentioned that ‘since the Chinese financial market is still not very open to foreign firms, many foreign governments also adopt similar strict regulations on Chinese banks’ (Guangzhou, 16 July 2013).

Note: This Research Bulletin has been published in Urban Studies, (2017), OnlineFirst |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||