GaWC Research Bulletin 168 |

|

|

INTRODUCTIONThe growing impact of globalization in widening social and spatial gaps and inequalities is widely studied in contemporary urban and regional research. One of the most striking characterizations of that impact was made by Petrella (1992), who termed globalization 'a technological apartheid of the world underclass', a world in which 90% of its population live in a huge ocean of poverty, while the rest live in an archipelago of the affluent. In Israel, despite the start of its entry into the post-industrial age and its affiliation with the global economy in the late 1980s, the study of its spatial inequality was until the late 1990s directed at core vs periphery phenomena (Lipshitz, 1996; 1998) or at the impact of alternating regional strategies on the above (Kipnis, 1996). Only since the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the post-industrial age reached its climax and Tel Aviv was named a 'World City' [in evolution or behind] (Kipnis, 2001; 2005; Felsenstein and Shachar, 2002), has some research centered on the widening social gaps and on the emerging marginal social groups of Tel Aviv City (Schnell, 2002; Schnell and Benjamini, 2001). Attention has also been turned to the diminishing weight of the middle class, from 33% of the total number of households in 1988 to 26% in 2002 (Sinai, 2005). Sklair (1991; 2000) was the first to define the 'transnational capital class', the upper status group of the global economy. He suggested that this class, along with the operators of the Transnational Corporations (TNCs) - - the professionals, bureaucrats, merchants, communications moguls, and politicians -- all who savor the delights of the global economy, tend to exhibit a cosmopolitan lifestyle. Their lingua franca is English, and their prime objective is to secure a smooth performance of the global economy, disregarding the national government interests and the local old-time elite. A part from Sklair, contemporary researchers have generally shied away from study of the upper groups of the social ladder. Only at the turn of the 21 st century did Milanovic (2002) depict the unequal distribution of the world's wealth, calculating that the world's rich, amounting to only 1% of the global population, hold assets equal to those of 57% of lower income people. Stimulated by Milanovic, Beaverstock and his colleagues (2004) published their "Getting away with it? The changing geographies of the global superrich", which portrays the lifestyles and the economic function of the 'global super rich'. The listing of Israel 's wealthiest, most influential, and most knowledgeable has gained momentum since the late 1990s, when The Marker (since 2001) and later the Hebrew edition of Forbes (since 2004) started to issue yearly lists of these people. The daily newspapers followed suit, adding to their holiday magazines lists of the 'best in Israel ' . At the same time, professional organizations of artists, musicians, lawyers, and the like, and others, created Internet sites containing lists or numbers of their members according to their place of affiliation or by the area code of their personal telephones. These lists made it possible to initiate a research agenda on the Israeli elite in the spirit of Beaverstock and his colleagues (2004). This agenda became an urgent endeavor following a report issued by Adva Institute of Policy Research (Sinai, 2005). The report revealed that the social group who benefited most from Israel 's recent economic growth was upper income groups employed in high-tech and producers' services, and whose yearly income was $91,000 and more. Adva further claimed that the upper income groups were the prime beneficiaries of Israel 's economic growth, and that their income had increased parallel to the country's GDP (4.2% in 2004). In contrast, the yearly income of households in the 6th and 2nd deciles was only $23,000 and $12,500 respectively, and had remained constant over the years. This article, employing the abundant sources of data, is designed to depict the geography of the Israeli affluent, influential, and professional. More specifically, the following issues are discussed:

WHO ARE THE RICH, THE KNOWLEDGEABLE AND THE PROFESSIONAL?Who is a Rich Person?There are many definitions of the word "rich". Webster's New Dictionary of Synonyms (1978), for example, lists a few synonyms for a rich person, namely one who possesses more than enough to satisfy normal desires and needs. A rich person is wealthy if he/she has money, income, and producing property or intrinsically valuable things in great quantity. A person is affluent if he/she is well-to-do, namely he/she continually increases his/her material possessions. In their search for a definition of a rich person, Beaverstock et al. (2004) referred to Veblen (1899) who, in his The Theory of the Leisure Class offered the first sociological definition of a rich person. For Veblen this is someone who owns enough assets to liberate himself/herself from the need to work, and therefore allow him/her to have a lifestyle of leisure and of consumption. Ginsburg (2003) suggested that while it is relatively easy to define poverty in measurable terms, a quantitative definition of a rich person, which is also place- and class-differentiated, seems to be evasive and subjective. In her efforts to explore who is an Israeli rich, Ginsburg portrayed a few stereotypes, proposing, as a starting point, that a rich Israeli is one whose monthly expenses are $6,800 and he/she can be singled out mainly by his/her style of home and by make of car. Ginsburg revealed a few common elements in the stereotypes of a wealthy person: one who desires to do all he/she wishes - - to own an automobile and a home, to live a trouble-free life, and to secure a worry-free life for his/her successors in the generations to come. Conniff (2002) perceived the rich as 'subspecies' who rebut the value of money but maintain exclusive, pretentious and protected lifestyles. To feature on the Forbes 400 list, Conniff argued, does not necessarily mean that a person is wealthy. Such a person might be one who has just inherited $1 billion, resides in a Manhattan 's penthouse with a private swimming pool, or possesses a summer house, a private jet plane, a yacht and/or owns other valuable assets. Conniff further suggests that in the past rich people tended to reveal somewhat similar lifestyles; today their lifestyles are more individualistic, as attested by their diversified housing styles (Conniff, 2002). The discourse over the meaning of wealth ought to consider the rising social inequality, and the fact that the rich are becoming richer and the poor poorer. Bergesen and Bata (2002) reported that in 1980 the income of the 10% upper income group was 80 times higher than that of the lowest income group. In 2000 it was 120 times higher. They also show that seven million people whose invested capital is more than $1 million have altogether $27 trillion, and that this sum is expected to increase by 50% by the end of 2005. The world's super rich, according to Bergesen and Bata , account for some 0.25% of the world's population, but their assets are equal to those of the remaining 99.75% of the population of our planet. At the bottom of the wealth ladder there are the 'mass affluent', those whose yearly income is more than $100,000 (Bergesen and Bata, 2002). Beaverstock and his associates (2004) further advanced the notion of who is rich. They pointed out that if in the past a rich person was one who had control over a given amount of production factors, today's rich are the professionals, the managers and the [rich] investors who run the global economy. They are those who have benefited most from the structural shifts in the economy and in its labor market, and from the increased involvement of producers' services in the global economy that have commenced in the 1960s. It is important to note that In many cases the producers' services have operated in the global economy as functional networks, covering their entire area of influence ("hinterlands") across the globe ( Beaverstock et al., 2000 ). Beaverstock et al. (2004) perceive the current global economy as highly skilled, specialized, knowledge-intensive, and capable of operating within the global networks that produce elaborate customer-oriented goods. Top decision makers, managerial staff, employees people at the head office, and outsourcing professional experts, usually located in a 'world city', comprise the hard core of the global capitalist elite. Its members, in charge of the smooth running of the global economy and also those who harvest most of its profits, are also referred to as the 'global super rich' by IFSL1 (2001). According to Beaverstock and his colleagues (2004), the spatial and economic activity systems of the world's rich are determined by their viewing the world externally rather than internally; they see themselves as citizens of the world regardless of their local (national) identity; they adopt 'global' lifestyles as evident in their image, consumption habits, use of luxurious facilities such as VIP lounges at airports, luxurious hotel suits, exclusive clubs, gourmet restaurants, and so on. All these are known as 'the right place to see and to be seen'. To sum up, Beaverstock and his associates (2004) propose a clear-cut distinction between the various classes who constitute the global super rich community. At the top are those who own the resources needed to activate the global economy. They seem to resemble Sklair's (1991; 2000) Transnational Capital Class, already noted. At a lower level are the knowledge-rich professionals and the managers, made affluent by their own skills, who are in command of the efficient production, trade, and investments of multinational corporations operating in the global economy (Beaverstock et al., 2004) . THE ISRAELI RICHIn 2000 The Marker, Israel 's business magazine published the first list of Israel 's 500 wealthiest people, who for the purpose of this study were grouped into wealth units, representing an individual, a family, or partners, whose wealth is recorded on the list as one total sum. Thereafter The Marker published yearly updated lists of Israel 's 500 richest people.2 The 2005 issue lists 1000 very rich Israelis for the first time.3 In 2004 the Hebrew edition of Forbes published a list of rich Israelis whose wealth was $100 million and more. This paper uses the Forbes list and The Marker's lists of 2003 and 2004, both with 500 wealth units, as just described. The entry threshold to the 2003 list was $10 million and that of 2004 was $25 million. This reflected the recovery of Israel 's economy (Dagan, 2004), which also resulted in increased social inequality. The total assets of the top 100 wealth units of The Marker's 2004 list was $32 billion, 24% higher than the total of the same group in the 2003 list (Eisenberg, 2004). The grouping of wealth units by the The Marker and by Forbes is the same, and like that of the Sunday Times. Israeli wealthy people-watching by the press has become the fashion in recent years (Tzuker, 2004). Tzuker reported that Merrill-Lynch 4 together with Globes (an Israeli economics daily) issued a list of 6,000 Israelis possessing $1 million and more. The list included 60 multimillionaires, 0.1% of Israel 's population, who together possess $20 billion, or 6.5% of the Israeli's total wealth. Another newspaper item (Lipski, 2005) commented on The Marker's 2005 list of 1000 Israeli rich. The writer noted that their total wealth assets were $20 billion, 50% of Israel 's GDP.5 Leading the 2005 list were 15 billionaires who possessed 25% of the wealth of the listed 1,000 (Lipski, 2005). THE AFFLUENT AND THE INFLUENTIAL: THE ISRAELI ELITEThe available definitions of the term 'elite' are numerous too. Wikipedia Free Encyclopedia online notes that t he originally French word means the ‘chosen or the elect’, marking a person or a group according to their access to education, money, prestigious genes, and so on. The attributes of a person deemed élite vary, and include, but are not limited to, high level of academic credentials, high level of experience in a given field, high intelligence, high natural skills such as athletic abilities, high level of creativity, and good taste. According to Wikipedia, the elite are a relatively small group whose personal abilities, specialized training or other attributes place them at the top of any field, and as a group whose views on a matter are to be taken most seriously, or people who fit to govern. As such, the elite occupy a special position of authority or privilege, and as a group they are set apart from the majority of people, who do not match up with their attributes. Lastly, Wikipedia suggests that a person who belongs to the elite possesses large amount of personal wealth that has stemmed from his/her elite attributes. For the Cambridge Dictionary online the elite is the richest, most powerful, best educated, and highly trained group in a society. Small and Whiterick (1986) in their Modern Dictionary of Geography perceived the elite as a small group whose members are the most influential in their own society, and those who control its sources of power. Easton (1995) viewed the elite as those who have the authority to decide who would have control over the resources of the society and decide who would accept what, and how. Lasswell (1965), who studied the nature of the political, the cultural, and the economic elite, asserted that the political elite includes people who are capable of imposing their authority; the cultural comprises people who master the humanistic properties of a society; and the economic exercises control over the material assets of their place and its members determine its economic agenda. In their study in Africa, Kotze' and Steyn (2003) show that by knowing who the elite are, and how the elite works, one can set up effective policies for the present turbulent globalization age. Besides the notion that the elite are those who have the wisdom of understanding and of knowing how to do what, Israeli research on the elite has primarily aimed at the following issues:

The study of the Israeli elite expanded in the second half of the 1990s with the publication of Etzioni-Halevy's (1997) Place at the Top - Elites and Elitism in Israel, and of her paper (2000) "Who governs Israel ?" Etzioni-Halevy identified a group of some 1,000 or even more Israelis who possess the power to determine, in many ways, what takes place in the country. They included politicians, businessmen, the wealthiest, government bureaucrats, senior officers of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and of the police, people in communications, key members of the judicial system, religious leaders, and the intellectuals. Many of the elite are Ashkenazi (European-born) males, who make use of their wealth and their access to government as their source of power. Their powers are further intensified by the circular linkages among the elites and between them and their buddies . The Israeli elite are elitist in the sense that Israel is deeply divided and unequal. Israel, which formerly was perceived as a society with small discrepancies between those at the top and those at the bottom, has since the mid-1990s displayed significant disparities among, for example, the rich and the poor or between the affluent 'northerners' and the less favored 'southerners'. These gaps are articulated in terms of access to resources, services, and benefits (Etzioni-Halevy, 1997; 2000).6 Etzioni-Halevy also made a distinction between the elite and the elitists. The former are known as the' finest', the cream of Israeli society; the latter, who by and large are able and decent individuals, might also include some with different qualities. Regardless of their manners, the elitists are those who manage the resources of information and knowledge, possess considerable political and organizational powers, and often determine the course of events.7 Since early 1960s other attempts have been made to identify new elite affiliates. Schweitzer (1984) reported that in those years Moshe Dayan and Shimon Peres, then two of the young emerging leaders of the Labor party, maintained that to revitalize Israel's national agenda, a departure should be made from the old farming and military elite, and the leadership should assigned to the foremost young leaders who had emerged from the immigrant populations of the new/development towns.8 Weiman (1999) introduced the communication 'rating elite', consisting of media stars whose status is determined by their rating index and not by their genealogy. The communication elite, according to Weiman, has managed to force the old elites to dance to its tune, thereby exerting a negative impact on Israeli society and its cultural life. Important too are Lin's (2000) and Odenheimer (2001) studies, which signify Israel 's affiliation with the global economy. Lin dubbed the emerging business elite the 'stock exchange tax coalition', made up of a few industrial conglomerates that produced most of Israel 's GDP in the late 1990s. Odenheimer characterized the high-tech elite as those with 16+ years of schooling, and whose personal income was 1.7 times higher than the national average. THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE AFFLUENT, THE INFLUENTIAL, AND THE KNOWLEDGEABLEAttributes of the Geographical SpaceAgglomerated urban centers, usually a central city and a few selected suburbs of its metropolis, loaded with a range of 'psychological rewards' (Buswell, 1983) and performing as a 'white collar' ambience (Malecki, 1980), are the preferred place of residence of the elite. These agglomerated centers, in addition to the anticipated rewards, offer the infrastructure and facilities needed to boost a complex net of linkages within and between the quaternary and the quinary sectors9 that run the global economy. Rich and diversified 'psychological rewards' epitomize urban places that are rich in cultural life, in public and consumer services, and in employment opportunities, most of which are geared to the 'knowledge-based economy' (Park, 2001; van der Laan, 2001; Kipnis, 2005). A place renowned for its 'psychological rewards' is believed to secure its vitality from its local 'creative class' (Florida, 2002; 2004a), a distinctive elite group composed of academic and scientific workers, writers, designers, architects, stage and movie actors, musicians, painters and sculptors, dancers and the like. Vital elements of a knowledge-and creativity-rich environment are the three Ts identified by Florida (2004a):

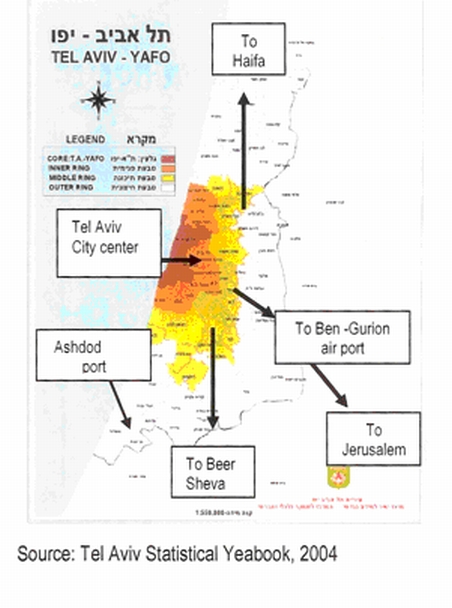

In his The flight of the creative class Florida (2004b) envisioned the 'tolerance' attribute of a place as the most important in order to attract quaternary and quinary skilled labor, namely the knowledgeable professional and managerial elite.12 13 HYPOTHESESIn order to expedite the absorption of more than 1,000,000 immigrants who entered during the 1990s, Israel had to replace its spatial planning policy of population disposal (Shachar, 1971) with one advocating reliance of the entire national territorial space on Israel's four metropolitan regions: Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, and Beer Sheva (NPBC, 1992). This policy is best reflected by the two 'economic' scenarios proposed in Israel 2020: A General Plan for Israel for 2020 (Mazor and Sverdlov, 1997). These scenarios, which mirrored the realities of Israel's swift entry to the post-industrial age and its affiliation with the global economy , posited exclusive reliance of Israel's spatial and socio-economic development on producer services and the high-tech industries, both with their main anchor in Tel Aviv. Taking this national spatial order, together with the obvious fact that Greater Tel Aviv has a superfluity of production factors, our hypothesis is that wealthy, knowledgeable, and influential Israelis tend to cluster, alongside the creative class, in Tel Aviv City and in its metropolitan area. As a result, the clustering process, accompanied by severe 'polarization effects', could result in a clash: on the one hand Israel is developing a national spatial order of a 'polarized national hard core', metaphorically described as "a huge head with no mass [body]",14 yet on the other hand the strong polarization effects would spur a speedy upgrading of the status of Tel Aviv City, along with its metropolis, as a fully pledged 'world city'. THE FINDINGSIsrael's 'Creative Class'Research of the 'creative class' pursued by Florida (2002; 2004a) is still in its early stages, and much of its conceptual themes are questioned by many (e.g., Cascio, 2005; Jacobs, 2005; Jeppesen, 2004). Jeppesen, the most critical among the researchers, reports that fieldwork in five European cities determined that Florida ’s thesis that growth is inspired by the 'creative class', is somewhat dubious. Such critiques notwithstanding, Florida deserves credit for creating a logical conceptual framework. 15 It is only fair to note here that t he first to anticipate a link among the 'creative' skills of a place was Bruce Stanley (2003), 16 who emphasized the significant role of the 'creative services' sector as a vital attribute of world city phenomena. Florida's main point is that a tolerant urban environment (one of the three Ts listed earlier) is a prerequisite for creating economic growth in a city, and that a tolerant ambience is closely related to favorable local attitudes to gays, artists [and other creative people], and immigrants, who signify tolerance. By extending the concept of the creative class, it could be perceived as a seminal element that helps create the place's 'psychological rewards', so vital for the Talented (the creative human capital who engage in creative occupations), and for those who operate the Technology (which stimulates the level and density of high-tech innovative activity). Both envelop all those who run the global economy, in our case in Greater Tel Aviv. Table 1: exhibits the preliminary data collected in a pilot survey of Israel 's main groups of people presumed to belong to the 'creative class'. Observe how most of the groups' members tend to cluster in Tel Aviv City and/or its metropolis. Notwithstanding the obvious variations, all groups have larger concentrations than the percentage distribution of Israel 's population in Tel Aviv City (5%) and the rest of the metropolis (40%) at the end of 2003. Of special interest is the distribution of painters and sculptors, stage actors, singers, dancers and their supporting agents, architects, and physicians. As to the first two groups, painters and sculptors and stage performers, is was not possible at this stage of the research to split those who live in Tel Aviv City off from those residing in the rest of the metropolis. Still, we assume that the majority of them dwell in Tel Aviv City . Gal-Ezer (1997) provided an explanation for the decisive concentration of painters and sculptors in Tel Aviv City . Tel Aviv is the place, he wrote, where they come across their colleagues, their buyers, their audience, and their critics. Tel Aviv, Gal-Ezer concluded, is the artists' 'greenhouse'. Architects (number of firms or studios) and MDs constitute other categories. Architectural firms are found all over Israel , but the largest concentration is in Tel Aviv City . Even medium-size architectural offices located in other parts of Israel tend to have a satellite office in Tel Aviv or to form a partnership venture with a leading Tel Aviv architectural firm in order to expose themselves to the large Israeli market administered there. Similarly, Tel Aviv City and its metropolis are the hard core of Israel 's health and medical services. Some 80% of the 379 physicians ranked the ten best in their field work in Tel Aviv and the metropolis. Most of the MDs congregate in one major hospital in Tel Aviv City , and in four large and highly specialized suburban hospital clusters. Last but not the least, preliminary pilot data on the homo-lesbian community, who simulate the tolerant ambience of a place, indicate that they tend to cluster in Tel Aviv City . Our estimates are that one half of Israel 's male and female homosexuals live in Tel Aviv City , and some 20% reside in the rest of the metropolis ( Kama , 2003). The Influential Israelis and their Spatial OrderMost dictionaries define someone influential as a person of understanding, intelligence, and knowledge, and who has a say. Time Magazine (2005), in its "Time's 100 people of the century", avers that an influential person is someone who helped define the political and social fabric of his/her time. Many recent publications present detailed inventories of selected groups of influential people. These lists make it possible to categorize the emerging influential groups and to document their spatial distribution. Israel's most important publications here are The Marker magazine, the Hebrew edition of Forbes, the weekends and holidays' magazines of Israel's leading newspapers, and the increasing numbers of Internet sites of Israeli governmental, public, and private organizations. In the following attention is paid to influential people in the economic and political spheres; note, however, that they are present in other social or professional groups such as the intelligentsia, scientists, religious leaders, poets and writers, and athletes – indeed, in practically all fields wherein people lead, invent, innovate, and express themselves. As representatives of the latter list, figure 2 shows the 2003 spatial distribution of the place of work of Israelis with 'prestigious' occupations. Figure 2 introduces the description of the spatial distribution of other groups: Tel Aviv City with only 5% of Israel 's population had 25% of those holding 'prestigious' professions. If the rest of the metropolis is included, 53% of those employed in 'prestigious' jobs worked in Greater Tel Aviv, 1.3 times more than the share of Greater Tel Aviv in the total Israeli population. Besides its annual lists of Israel 's wealthiest, The Marker publishes yearly lists of the place of work and affiliation of the 100 most influential in the Israeli economy. The September 2004 list (The Marker, 2004b) highlighted the editorial deliberations that had accompanied their compiling the list. The most important item is that among those who were upgraded in the 2004 issue were people from the insurance industry, alongside those in government who led the reform in the insurance sector. Those who were downgraded were bankers and the banking system regulators, whose standing fell as a result of reform. Figure 3 shows the place of work of the 100 most influential people divided into three main sectors: businesses and producing services (including FIRE), government, and public institutions. Observe how Tel Aviv City dominates in businesses and producer services and in public institutions; the rest of the metropolis, mostly at two suburban sites, the Bursa and Herzeliya (Kipnis and Borenstein, 2001) is relatively strong in services. As might be expected, Jerusalem , Israel 's capital and the official seat of government, is conspicuous as the place of work of influential government officials. In conclusion, Greater Tel Aviv is the dominating core area of Israeli influential people in all non-governmental activities; Jerusalem is the home base of the most influential people in government. Yediot Achronot (2004) in its April holiday magazine listed the 50 women who led in business. The list contained personal attributes like age, education, role in Israel 's economic entity, and place of work. By means of the Internet telephone directory, the home addresses of 89% of the women were identified. Figure 4a shows that 76% of the women who led in business lived in Greater Tel Aviv: 30% of them resided in Tel Aviv City , an exceptional phenomenon in itself. The predominance of Tel Aviv City is all the more striking when the women's place of work is considered (figure 4b). Some 63% of the women who held prime position such as owners, directors-general, or divisional directors, or who served as key board members, were affiliated with businesses or institutions located in Tel Aviv City. Less than a quarter had their work place in a suburban location, with the Bursa in Ramat Gan and Herzeliya Pituach heading the list. The third group of influential people is Members of Knesset (the Israeli parliament) (MKs). They represent the politically influential group, in charge of allocating of national resources and approving area-related legislation. Many of their decisions with an economic flavor are heavily influenced by place or sector lobbyists. If in early statehood years the politicians, who were elected on nation-wide tickets, mostly expressed nation-wide sympathies, in today's politics MKs display predilections for their region of origin, notwithstanding the fact that they carry a "nation-wide commitment" and were elected on a nation-wide ticket. On the whole, MKs from the so-called "territories" ( Samaria , Judea , and Gaza ) and of the religious parties tend to support their electoral sectors. At the same time, MKs of secular parties tend most often to commit their power to securing the economic and social welfare of their own region of origin. Table 2: shows that 57% of the group of secular Knesset factions live in metropolitan Tel Aviv; 21% live in Tel Aviv City, significantly more than the 5% proportion of Tel Aviv City in the total population of Israel. In conclusion, three groups of influential people were examined: the 100 most influential Israelis; the women who lead in business; and the politicians who determine most area-related issues of Israeli's lives. All three groups, their national status notwithstanding, tend to nest in Greater Tel Aviv, with a significantly high concentration in Tel Aviv City . The Israeli Rich and their Spatial Order"Who pays the piper calls the tune" or "he who'll pay has the say" are common aphorisms alluding to the inherent power of the affluent in shaping the course of our social, economic, and spatial well-being, development, and prosperity. Israel is no exception, as evinced by the current trend to publish annual lists of Israel 's wealthiest people, initiated by The Marker in 2001 and later joined by Forbes (2004).17 In using both Forbes and The Marker for this article, only entries with capital assets of $100 million and more were included in the analysis. In both magazines an entry contained all persons who shared all the listed amount of wealth. They could be individual holders, a husband and wife, extended family members, or partners. To resolve this inconsistency, five wealth units, as described earlier, were defined. Table 3 shows the units and their distribution among the four wealth-size groups. It shows that in 2004, 75% of the units belonged to an individual owner; 12% of the units were of father and son(s); 5% of the units registered on the names of a husband and wife; and 4% were of brothers/sisters and partners. Among the wealth units owned by individuals, 11% had $1,000 million and more; 12% of the wealth units had a capital of $500 - $999 million; 45% had $250-$499 million; and 32% had $100-$499 million. The Marker (2004) reported that a significant upgrading of wealth took place between 2003 and 2004, reflecting the recovery of Israel 's economy. As a result, the threshold for inclusion in the list was raised from $10 million to $25 million. Table 4 shows the movements of wealth units across wealth-size groups. Note that the common trend was movement up the ladder, and the most visible increase was in the $500-$999 wealth size which increased from two wealth units in 2003 to ten in 2004. Important too is the fact that seven wealth units of $100 million in 2003 upgraded their group affiliation. Chi-squared analysis disclosed a significant difference (a = 0.01) in the distribution of wealth across wealth-size groups between 2003 and 2004. There were variations across industries and across wealth-size groups in the source of the wealth (Table 5 ). The variation in the former was significant with a = 0.001; in the latter, although it looks different, it's calculated Chi-squared is too small to be considered significant. The most visible differences are that the majority who made their wealth by their 'own hands' (self-made) engaged in the high-tech industry: 43% in 2004. The majority of those in the 'inheritance' category were in automobile imports (20%), shipping (17%), and the diamond business (5%). Together these three accounted for 42% of the inheritance group. The largest wealth-size group in the inheritance category was $250-$499 million (49%), while that in the self-made category was $100-$249 million (40%). The majority of the Israeli rich, 70% of them, reside in metropolitan Tel Aviv (figure 5a). Significant is the fact that more than fifth (21%) live in Tel Aviv City . Many of those listed as wealthy live abroad: 12% have an address in Israel and abroad, and 11% live abroad on a permanent basis. Many of them are among the upper wealth-size groups. Figure 5b shows the distribution of wealthy people who live in metropolitan Tel Aviv (accounting for 70% of the total). After Tel Aviv City , which heads the list, four suburban settlements account for 48% of the distribution. They are Herzeliya [Pituach] (19%), Savion (11%), Kefar Shemaryahu (10%), and Ramat Gan (8%). All are on the rim of the first ring of the metropolis. Much more concentrated is the distribution of the place of business of the super rich. Close to 90% are located in the metropolis: 38% in Tel Aviv City and 50% in the rest of the metropolis, with the majority in the Bursa in Ramat Gan and in Herzeliya industrial park [Herzeliya Pituach] (figure 5c). CONCLUDING REMARKSThe hypothesis that wealthy, knowledgeable, and influential Israelis cluster in Tel Aviv City and in its metropolitan area is endorsed. This implies that in response to the swift entry of Israel into the post-industrial age and its affiliation with the global economy, Greater Tel Aviv, and more so Tel Aviv City , evolved as the hard core of Israel 's economic, social, and cultural life. The emerging spatial model was associated with strong polarization effects that led to the development of a 'polarized' national spatial entity. Alongside the condensed territorial pattern, Tel Aviv City , along with its metropolis, reinforced its world city standing. The study of the geography of the super rich, initiated by Beaverstock and his associates (2004), has merit as a legitimate research topic, assuming that one also refers to the negative effects involved in the increasingly imbalanced distribution of the world's assets as described by Milanovic (2002). Milanovic covered the two extreme status groups: one defined by Petrella (1992) as the global 'techno-apartheid underclass' and the other the status group introduced by Sklair (1991; 2000) as the Transnational Capitalist Class. In asking [Should we] "getting away with it?" Beaverstock et al. (2004) implied that the investigation of the changing geographies of the global super rich should also examine possible ways and means to curtail the growing imbalances in the distribution of assets, and in access to resources, services, and opportunities, between the 'super status' groups and the rest of the world. Beaverstock et al. (2004) perceived the 'super rich' as stretched 'status groups' who strive to take control of the global economy. The stretched status groups, besides the super rich, consist of the managers, the influential people, and the knowledge-rich professionals of the quinary and the quaternary sectors, most of them wealthy by their own merit. Applying the above comprehensive conceptual meaning of the 'super rich', this paper has recorded the geography of Israel's affluent, influential, and professional people and has set out the local state of affairs that facilitates their acting as 'human agencies' endeavoring to advance Israel's globally oriented economy. It has depicted their impact on two possible processes: has their presence as a stretched 'status group' of the Israeli affluent in [Greater] Tel Aviv, helped the metropolis to further its 'world city' standing? Or has the substantial agglomeration of the stretched 'status group' in [Greater] Tel Aviv exacerbated the unbalanced structure of Israel 's national space? The fact is that the two impacts prevail. The qualities that help a place to attract the members of the stretched 'status group' are the intensive concentration of 'psychological rewards' that act as a platform for Florida's (2004a) three Ts – talent, technology, and tolerance, a prerequisite for a 'white-collar environment'. These qualities do exist in Tel Aviv City and in its metropolis. Greater Tel Aviv evinces explicit predominance in top R&D oriented high-tech industries; it exhibits an abundance , in quality and variety alike, of FIRE and of producer services functions, some of them linked to the global economy as elements of a 'world city network' envisioned by Beaverstock et al. (2000). Greater Tel Aviv acts as Israel 's anchor to the global economy and a vital element in the 'meta-geography' of the 'world city network'. It has evolved into the unchallenged nucleus of Israel 's economy and elite. Yet there is a 'hitch' somewhere in this dominant position. Despite Israel 's population dispersal policy adopted in 1949, Israel is still vulnerable to increasing polarization effects, with an unbalanced distribution of its population and economic wealth. As a polarized entity, having excessive free production factors, Tel Aviv has become a lodestone for young Israelis, mostly aged 25-34, and their rate of increase in Tel Aviv City is three times higher than that of the total city population. They come from all over Israel . In the early 1990s Tel Aviv was cataloged as an 'old city', with 19% of its 1990 population aged 65+ years (9% of the total Israeli population) and its 24-34-year-old age group was 16%. By the end of 2003 the above age groups were 17% (9.9% of the Israeli total) and 23% respectively; Tel Aviv City is described as the city of the young. Migration of economic activities has followed suit. Haifa , for example, the second most important economic center, has lost most of its historic port-related industries. Some industries have ceased their operations and their employees have become 'structurally' unemployed, while other industries have relocated to the peripheral region of Galilee . Simultaneously, most headquarters of public and private enterprises, a vital element in the economy of Haifa in the past, have left for Tel Aviv. The sole head office remaining in Haifa is that of the Israel Electricity Company, although even this company has its main decision-making and control functions in Tel Aviv City . Now, with a much improved railway system, Tel Aviv might radiate its polarization effects still more powerfully on Haifa and Beer Sheva (the southern metropolis).18 Likewise, the improved passenger rail-road system will very likely intensify the polarization effects originating in Tel Aviv. On the positive side, this intensification would boost Tel Aviv's 'world city' status. On the negative side these processes are expected to worsen spatial inequality, weaken other regions, and force them to enhance their reliance on Tel Aviv. More research is needed to evaluate the causes and consequences of a national territory having a single multi-function hard core. This research is also anticipated to explore ways and means to revise the adverse processes, and to propose a policy to modify the emerging trends into a more balance spatial form. If such a national spatial policy is necessary in any normal geopolitical situation, it is all the more imperative in the case of Israel , a country heavily affected by turbulent geopolitical processes. Notwithstanding the quite endeavor to upgrade Tel Aviv's world city standing, it is important to grasp that a balanced spatial order is no less essential. REFERENCESBeaverstock, J. V., Hubbard, P. J. and Short J. R. (2004). “Getting away with it? The changing geographies of the global super rich”. Geoforum, 35 (4) : 401-407, and in Research Bulletin 93, www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/rb/rb93.html Beaverstock, J. V. Smith, R. G. and Taylor, P. J. (2000). World city network: a new meta geography". Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 90, 1: 123-134. Also, a Research Bulletin # 11, (1999). www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc Bergesen, A. and Bata, M. (2002). “Global and national inequality: Are they connected?” Journal of World System Research, 8 (1): 130-144. Buswell, R. J. (1983). “Research and development and regional development: A review”, in Gillespie, A. (ed.), Technological Change and Regional Development. London : Pion: 9-22. Cambridge dictionary online http//dictionary.cambridge.org Cascio, J. (2005). "The greening of the creative class". www.worldchanging.com/archives/002610.html Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society. Oxford : Blackwell. Central Bureau of Statistics (selected years), Statistical Yearbook of Israel . Jerusalem (in Hebrew). Conniff, R. (2002). The Natural History of the Rich: a Field Guide. New York : Norton. Dagan, M. (2004). "The wealth threshold raised to $15 million". Haaretz, 1 April 2004 (in Hebrew). Easton D. (1995). Regime and Discipline: Democracy and the Development of Political Science. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press. Eisenberg, A. T. (2004). "Ranking the 100 wealthy Israelis: Who is upgraded and who downgraded?" Maariv, 5 April 2004 (in Hebrew). Etzioni-Halevy, E. (1997). A Place at the top: Elites and Elitism in Israel. Tel Aviv: Tzerikover. Etzioni-Halevy, H. (2000). "Who govern in Israel ?" Mifneh, 29: 14-17 (in Hebrew). Felsenstein, D. and Shachar, A (2002). "Globalization processes and their impact on the structure of the Tel Aviv metropolitan area". In Felsenstein, D., Schamp, E.W. and Shachar, A. (Eds.), Emerging Nodes in the Global Economy: Frankfurt and Tel Aviv Compared . Dordrecht : Kluwar Academic, 35-53. Florida , R., (2002). “ Bohemia and economic geography”. Journal of Economic Geography, 2: 55-71. Florida , R. (2004a). The Rise of the Creative Class. New York : Basic Books. Florida , R. (2004b). The Flight of the Creative Class. New York : HarperBusiness. Florida , R. (2005). "The real economic threat". The Star Ledger, N.J. 24 April 2005 . Forbes (2004). "The 400 richest Americans and the 100 Israeli richest". Forbes Hebrew edition. Gal-Ezer, M. (1997). "Winners and losers: the lifestyle of the painters and sculptures". Devarim Acherim, 2: 92-115 (in Hebrew). Ginsburg , A. (2003). "How much money does one need to be rich?" Haaretz, 24 Dece. 2003 (in Hebrew). IFSL - International Financial Services London (2002). International private wealth management. London: IFSL. Israeli painters and sculptures (2004). www.artisrael.co.il (in Hebrew). Israel 's telephone directory (2004). www.bezek.com.il (in Hebrew). Jacobs, K. (2005). "Why I don't love Richard Florida". www.metropolismag.com/cda/story.php?artid Jeppesen, T. (2004). "The creative class struggle". Konure, 10: 20-26. Kama, A. (2003). The newspaper and the nloset, communication patterns of homosexuals. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad (in Hebrew). Kipnis, B. A. (1996). "From dispersal to concentration: Altering spatial strategies in Israel ". In Gradus, Y. and Lipshitz, G. (Eds.), the mosaic of Israeli geography. Beer Sheva: Ben-Gurion University Press: 29-36. Kipnis, B. A. (1997). "Dynamics and potentials of Israel 's megalopolitan processes". Urban Studies, 34 (3): 589-501. Kipnis, B. A. (1998).“Location and relocation of class A office users: Case study in the Metropolitan CBD of Tel Aviv, Israel ”. Geography Research Forum, 18: 64-82. Kipnis, B. A. (2001). “Tel Aviv , Israel – a World City in Evolution: Urban Development at a Dead-End of the Global Economy”. GaWC Research Bulletin #57, at GaWC site: www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc, also in Pak, M. (ed.) (2004) Cities in T ransition . Ljubljana : Department of Geography, the University of Ljubljana : 183-194. Kipnis, B.A., (2005). "Spatial concentration, economic elite and knowledge-based economy: The case of Metropolitan Tel Aviv" . Paper presented at the Open Conference 2005: Knowledge and Regional Economic Development, Barcelona , Spain , June 2005. Kipnis, B. A. and Borenstein, O (2001). "Patterns of suburban office development and spatial reach of their office firms: A case study in Metropolitan Tel Aviv, Israel ”. In Felsenstein, D. and Taylor, M. (Eds) Promoting local growth. Aldershot : Ashtgate: 255 – 270. Kotze', H. and Steyn, C. (2003). African elite erecipitation: AUAND NEPAD. Johannesburg : Konrad – Adenaur-Stiftung, Occasional Papers. Lasswell, T. E. (1965). An Introduction to concept and research. Boston : Houghton Mifflin. Lin, Y. T. (2000). "The state, the business elite, and the stock exchange tax". Tzedek Halukati in Israel : 223-259 (in Hebrew). Lipshitz, G. (1996). "Core vs. periphery in Israel over time: Inequality, internal migration and immigration". In Gradus, Y. and Lipshitz, G. (Eds.), The Mosaic of Israeli Geography. Beer Sheva: Ben-Gurion University Press: 13-28. Lipshitz, G. (1998). Country on the move: migration to and within Israel , 1948-1995 .London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Lipski, N. (2005). "The list of 100 Israeli rich – the upper deciles count more money". Haaretz, 11 Feb. 2005 (in Hebrew). "The best in Israel ". Maariv, 5 April 2004 (in Hebrew). Malecki , E. J. (1980). "Corporate organization of R&D and the location of technological activities", Regional Studies: 14: 219-34. Mazor, A. and Sverdlov, A. (1997). Israel 2020: A general plan for Israel for 2020 . Haifa : The Technion (in Hebrew) Milanovic, B. (2002). "True world income distribution, 1988 and 1993: First calculated based on household surveys alone". The Economic Journal, 12: 51-92. NPBC (National Planning and Building Commission) (1992). Integrated Master Plan for Construction, Development and Absorption of Immigrants. Tel Aviv: Lerman & Lerman Architects (in Hebrew). Odenheimer, M. (2001). "A non-theoretical issue". Eretz Acheret, 5:26-29 (in Hebrew). Ostendorf, W. (Ed.), Styles of segregation and desegregation. Aldershot : Avebury: 39-66. Park, S.O., (2001). "Knowledge-based industry for promoting growth". In Felsenstein D. and Taylor , M. (Eds.), Promoting Local Growth, Process, Practice and Policy. Aldershot : Ashgate: 43-61. Petrella R. (1992). “Techno-apartheid for global underclass".Los Angeles Times, Metro section, 6 Aug. 1992 . Schnell, I. (2002). Segregation in everyday life spaces: a conceptual model. In Schnell, I. and Ostendorf, W. (eds.) Styles of Segregation and Desegregation. Aldershot : Avebury: 39-66. Schnell, I. , and Benjamini, Y. (2001). "The socio-spatial isolation of agents in everyday life spaces as an aspect of segregation". Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 91: 622-633. Schweitzer, A. (1984). Upheaval. Jerusalem : The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies (in Hebrew). Shachar, A. (1971). " Israel 's development towns: Evolution of a national urbanization policy". Journal of American Institute of Planners, 37: 362-372. Sinai, R. (2005). "A report: The upper deciles benefit more from the economic growth". Haaretz, 2 Jan. 2005 (in Hebrew). Sklair, L. (1991). Sociology of the global system: social change in global perspective. Baltimore : The Johns Hopkins University Press Sklair, L. (2000). “The Transnational capitalist class and the discourse of globalization”. www.theglobalsite.ac.uk Small, J. and Whiterick, M. (1986). A Modern dictionary of geography. London : Edward Arnold. Stanley, B. (2003). "'Going global' and wannabe world cities: (Re)conceptualizing regionalism in the Middle East ". In Dunaway, W.A. (Ed.), Emerging Issues in the 21 st Century World-System. Vol. I: Crisis in Resistance in the 21 st Century World-System. Westport , CN: Praeger: 151-170. Also in the GaWC site, Research Bulletin, 45 (2001). The Israeli association of Artists (2004). . www.emi.org.il (in Hebrew). The Israel Knesset (20 .04 ) www.knesset.gov.il (in Hebrew). The Marker (2003). A directory of the Israeli rich in 2003. Tel Aviv: The Marker (in Hebrew). The Marker (2004a). "The 500 Israeli rich in 2004". Tel Aviv: The Marker (in Hebrew). The Marker (2004b). "The most influential people in Israel ". Tel Aviv: The Marker (in Hebrew). The Marker (2005). "A directory of the Israeli rich in 2005". Tel Aviv: The Marker (in Hebrew). The National Planning Commission (NPBC) (1992). An Integrated National Master Plan for the Absorption of Immigrants, Construction and Development – TMA 31. Jerusalem (in Hebrew). Thrift, N. (2000). "Performing culture in the new economy”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90 (4): 674-692. Time magazine (2005). "Time's 100 people of the century". www.time.com/time/time100/ - 27k - 25 May 2005 Tzuker, Z. (2004). "The road to wealth". Globes, 15-16 June 2004 (in Hebrew). van der Laan, L. (2001). "Knowledge economies and transitional tabor markets: New regional growth engines". In Felsenstein D. and Taylor , M. (Eds.), Promoting Local Growth, Process, Practice and Policy, Aldershot : Ashgate, 331-346. Veblen, T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class . New York : Macmillan; 1994 edition London : Routledge. Weiman, G. (1999). "The new elite". Ha'ain Hashvi'it, 21: 36 -37 (in Hebrew). Wikipedia Free Encyclopedia online http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia Yediot Achronot (2004). "Women who lead in businesses". Yediot Achronot, 5 April 2004 NOTES* Baruch A.Kipnis, Professor of Geography and Planning, the University of Haifa, Israel baruch@univ.haifa.ac.il 1 International Financial Services London . 2 The method of ranking of wealth by the The Marker is similar to that used by Forbes and by the Sunday Times. 3 By the time the 2005 issue appeared this paper was almost complete. An analysis of the 2005 list will be made in a planned Ph.D. thesis. 4Merrill Lynch is one of the world’s leading financial management and advisory companies, with offices in 36 countries and total client assets of approximately $1.6 trillion, at the end of 2004. 5 The percentage given should be 17-18% of Israel 's GDP, estimated at $114 billion in 2003 . 6 These gaps are far wider now in 2005. 7 The list of the elitists does not include rich people only. Those who belong to the elitist cliques might include a few respected professionals as well as those 'known' as having 'strong' political standing at the core circles of political parties. 8 Failure to act resulted in the Labor collapse in the 1977 elections, which the parties that later united to form the Likud won. Among the elected Knesset members were young mayors of the new towns, some of whom, such as Moshe Katsav (currently Israel 's president) and Meir Shitrit (currently minister of transport), still hold central public and government positions. 9 The quaternary sector supplies professional producers and consumer services; the quinary sector engages in decision making and control. Both are vital for the efficient functioning of the global economy and have been a leading factor in the evolution of KBE. 10 An important measure of tolerance is the size and role of the lesbian-gay community of a place. The correlation between the human creativity index and the homo-lesbian index was R = 0.65 significant at a = 0.01. 11 The first to highlight these attributes was Castells (1996) who linked the technological up rise of the 1970s to the culture of freedom, individual innovation, and entrepreneurship that had grown up in the American campuses of the1960s. 12 According to Florida (2004b; 2005) the flight of the creative class is mainly from the USA to Canada and Europe , particularly to the UK and the north European countries. 13 Large concentrations of 'creative class' groups were found in New York , Los Angeles , San Francisco , Boston , Washington DC , and Seattle . All revealed high tolerance indices ( Florida , 2000). 14 A. Shachar coined the phrase during a debate in a panel held at a meeting of the Israel Association of Geographers in Haifa in 1995. The debate explored Israel 's emerging postindustrial urban system. 15 A graduate thesis, designed to explore Tel Aviv and Haifa 's creative services and class, is in progress. 16 Stanley placed the first draft of his manuscript on the GaWC site: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/ 17 The Marker lists for 2001, 2002, and 2004 were published as magazine issues, and those for 2003 and 2005 as Directories. Until 2004 The Marker listed 500 entries ('wealth units'). The 2005 Directory had 1000 entries for the first time. In 2004 the Hebrew edition of Forbes joined the trend and published an appendix to its American 400, listing 100 super-rich Israelis whose wealth was $100 million and more (Forbes, 2004). The Marker for 2005 appeared after the detailed analysis of The Marker for 2003 and 2004 and of Forbes for 2004 was complete. The data of The Marker 2005 Directory will be used by an entrant Ph.D. student. 18 A Ph.D. study exploring the impact of the upgraded rail system on Tel Aviv's role as the hard core of Israel 's labor ??shed is in progress.

Table 1: The spatial distribution of Israel's 'Creative class' groups (preliminary list) in percentages

Sources: Statistical Yearbook of Israel 2004; Yellow pages, 2004; The best in Israel (Maariv, 5.April 2004) * Ashdod not included ( Ashdod natural area is officially included in metropolitan Tel Aviv) ** Ashdod included

Table 2:Place of residence of Members of Knesset (parliament) (percentages)

Source: The site of the knesset www.knesset.gov.il Table 3:Distribution of wealth by type of wealth unit: Israeli super rich with $100 million and more in 2004 (percentages)

Source: Forbes, 2004. Table 4:Changes in wealth distribution between 2003-2004 by wealth-size groups of wealth*

Source: The Marker, 2003; 2004b Table 5:Distribution of wealth units by source of wealth and by main industry and by wealth-size groups of wealth 2004

Source: Forbes, 2004. Figure 1: METROPOLITAN TEL AVIV

Figure 2: Source: Statistical Yearbook, 2003 Figure 3: Figure 4: Source: Yediot Achronot, 2004 Figure 5: Source: The Marker, 2003; 2004; Forbes, 2004.

Edited and posted on the web on 8th August 2005 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||