GaWC Research Bulletin 120 |

|

|

|

This Research Bulletin has been published in MM Amen, K Archer and MM Bosman (eds) (2006) Relocating Global Cities: From the Center to the Margins Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 23-47. Please refer to the published version when quoting the paper.

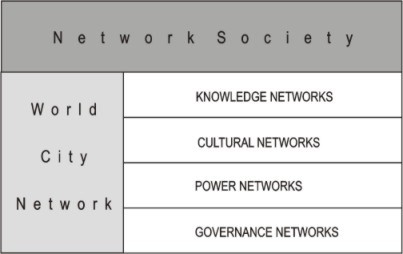

INTRODUCTION: THE RISE OF FRANKFURTIt is hard to pinpoint the beginning of Frankfurt's transformation from German city to 'world city' status. Some academics have put the time as early as the late nineteen sixties when economic activities that were to become the axes of the global economy began to concentrate in Frankfurt (Keil and Ronneberger 2000). But by the late eighties, Frankfurt had attributes which appeared to set it apart from other cities within Germany as a 'world' rather than a national city. The landmark skyline of the financial and business district today denotes the city's current role as a prominent international hub and the economic globalization literature would suggest that as Germany's leading financial centre, Frankfurt should be on a rising trajectory (Bördlein 1999, Felsenstein et al. 2002, Harrschar-Ehrnborg 2002). In spite of Frankfurt's ascendancy to become Germany's main financial centre (see Holtfrerich 1999, Schamp 1999), Germany's historical development and relatively decentralised national political and economic structure has meant that Frankfurt has lacked the prominence that London has had in the UK. Whereas the UK financial and business services industry is London, Frankfurt is one of several German cities with complementary functional specializations (Blotevogel 2000). An important recent question has been whether changes associated with European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), with the UK outside, would change Frankfurt's status in a 'Europe of Cities' bringing it out from London's long shadow. Can Frankfurt rival London? This is the question that stimulated the research reported in this chapter. The chapter is divided into four parts. The first part briefly discusses Frankfurt's position amongst world cities, which sets the context for the research. The bulk of the chapter is constituted by parts two and three that provides a detailed empirical analysis of Frankfurt's relations with London at the onset of the introduction of the Euro, and organizational tensions pertaining to firms in both cities. Finally, several conclusions are reported, the gist of which are that, for the foreseeable future, London will most likely continue to cast a long-shadow over all of its European world city neighbours. FRANKFURT IN THE SHADOWThe purpose of this section is to review the evidence for the importance of Frankfurt as a contemporary world city. The argument begins with the conventional concern for locating cities within urban hierarchies before developing a network approach to understanding the current role of Frankfurt in the world economy. This discussion is important because it is necessary to understand what sort of 'shadow' London casts over Frankfurt. Frankfurt in the 'World City Hierarchy'For nearly two decades, studies of relations between world cities have been dominated by Friedmann's (1986) identification of a 'world city hierarchy'. He classified cities according to the way they 'articulated' production and markets in the world economy. In Friedmann's hierarchy, Frankfurt was designated as a 'primary world city' (in the core economies), ranked fourth (behind London, Paris and Rotterdam) in the European space economy (with Zurich fifth; and Brussels, Milan, Vienna and Madrid listed as 'secondary' European cities) (see his Table A.1, The World City Hierarchy). Of course, such rankings were based upon an analysis of 'attribute data', for example the number of headquarters for TNCs or international institutions. No other German cities were identified in Friedmann's (1986) hierarchy. Almost ten years on, Friedmann (1995, 35), drawing on Keil and Lieser (1992), noted that Frankfurt was the 'premier German global city.' Frankfurt was newly designated in his hierarchy of 'spatial articulations' (1995, 24) as a 'multinational articulation' for western Europe (along with Miami [which articulated into the Caribbean/ Latin America], Los Angeles [Pacific Rim], Amsterdam or Randstad and Singapore [SE Asia]). Frankfurt was a city which articulated capital in the western European space of flows, primarily through its position as a financial centre, but was not included as one of Friedmann's 'global financial articulations', London, New York and Tokyo, which sat atop his hierarchy of thirty world cities (1995, 24, Table 2.1). Inspecting Friedmann's (1995) positioning of European world cities shows that Paris/France, Zurich/Switzerland and Madrid/Spain can be identified as important 'national articulations', and in the case of Germany, Munich and Düsseldorf-Cologne-Essen-Dortmund (Rhine-Ruhr) have been designated as 'sub-national/regional articulations'. Thus there is no German 'national articulation', its world cities are either multinational or sub-national articulators. This German particularity will appear in a modified guise in the empirical work below, but the key point to note first is the fact that Frankfurt never makes the top tier in Friedmann's hierarchy: London is consistently shown as Europe's only world city at the hierarchy's apex. The importance of London in comparison to Frankfurt is supported by the statistics shown in Tables 1 and 2. Using 12 basic indicators of financial prowess, London/UK is found to be leading Frankfurt/Germany on ten of them. But it is important to understand that such figures do not indicate that London is above Frankfurt in a new urban hierarchy. These are attribute measures that show London to be a far larger financial centre; they say nothing about how the two cities are linked, whether hierarchically or not. Attributes provide measures of size that allow cities to be ranked but should not be confused with hierarchical processes (Taylor 1997). For the latter to be shown there needs to be direction from above impinging on the actions below. This requires measures of relations between cities, not simple ranking by size. Thus the two tables show London to be more important as a world city, a finding consistent with Friedmann's 'world city hierarchy' but it does not confirm the existence of the latter. In fact, it is not at all clear in what sense 'London' directs 'Frankfurt' as a hierarchical process. But such hierarchical theories originated before the contemporary ICT era and cannot explain the role of these cities in globalization (Beaverstock et al. 1999). Frankfurt in a World City NetworkBecause world cities operate as bases for transnational economic activity they are inevitably tied together through multiple connectivities within a new space of flows that traverses what Castells (2000) calls the old 'space of places'. This suggests that unpacking the dominance of London's shadow in a 'Europe of Cities' requires more than adding on an extra scale to traditional models of national urban hierarchies (see Taylor and Hoyler 2000, Taylor 2003). In a global space of flows wherein electronic communications eliminate distance costs there is no intrinsic reason for cities to be arranged hierarchically. It is for this reason that conventional ways of viewing inter-city relations have to give way to more flexible models. In this research, world cities are interpreted as constituting a network: following Castells (2000), they are the nodes that define a world city network. In order to investigate why Frankfurt remains in London's long shadow, despite the introduction of the Euro at the end of the 1990s, it is therefore necessary to study the relations between Frankfurt and London within this world city network. This is a challenging research goal given the multiplicity of material and virtual flows that connect contemporary global cities across geographical space. The starting point is to derive a careful specification of the world city network (Taylor 2001). The world city network is not like typical networks where the nodes (usually members of a group) are the actors that produce the network. In the generation of a contemporary world city network, it is advanced producer service firms that are the key actors in world city network formation. This network is a triple-level structure in which the nodal and network levels are joined by a 'sub-nodal' level of service firms within the nodes (cities). This defines an interlocking network in which the firms link together the cities through their office networks (Taylor 2001). Thus financial and business service firms are the creators of the world city network through their global location strategies for servicing their clients. These firms have become the dominant internationally organised activities in the world economy because they must operate as cross-border networks (made possible by developments in ICT) to provide a 'seamless' service for their corporate customers anywhere in the world (see Dicken 1998, Lee and Schmidt-Marwede 1993, Porteous 1999). To do this effectively, and compete successfully with market competitors, their city-based offices must function as co-operative cells within the global organisation. In this way these myriad office networks constitute a world city network with information, knowledge, ideas, plans, intelligence, strategy, instruction and all other communication linking the cities together across the globe. There is a very important corollary from replacing the hierarchical model by a network one. Hierarchies are premised upon a process of competition, this is how the basic structure is created and reproduced. It follows that in a world city hierarchy the prime relation is competitive as cities strive to climb up the rungs of the structure. Networks are premised upon processes of co-operation - without this fundamental mutuality any network will cease to function and collapse (Powell 1990). It follows that in a world city network, cities share a synergy of roles that are complementary within the operation of the network overall. Cities, therefore, do not themselves compete: the competition is between the firms operating in various global service markets. This has important theoretical and policy implications. There is a large literature on city competition that feeds into city boosterism policy making (encouraging city administrations to compete for mobile financial and business services). This is a place-based discourse and practice that largely ignores 'external' factors in the success of cities. Of course, it is important for cities to attend to their locale to attract firms but this will always be a minor feature compared to the general process of world city network formation. No amount of national and city government boosting of Kuala Lumpur as a place for business will lead to it replacing Singapore as the key South East Asian node in the world economy. The message is that cities need to be far less inward-looking (place-orientated) and attend especially to their networks (Beaverstock et al. 2002). Guided by this interlocking network model, data have been collected for 100 global service firms (see Appendix 1) across 315 cities (Taylor et al. 2002). Using basic network analysis techniques, measures of interlock connectivities between cities have been computed from this data to provide global network connectivity values (Taylor 2001, Taylor et al. 2002). The global network connectivity of a city indicates its relational importance as a node within the world city network: the top 20 cities ranked by this measure are shown in the left columns of Table 3. This relational measure confirms the importance of London compared to Frankfurt shown above using attribute measures (Tables 1 and 2): London is ranked top and Frankfurt ranked a relatively lowly 14th (behind 4 other European cities). Note that this way of portraying Frankfurt compared to London is much more sophisticated because it is a relational measure (involving 315 cities in all) with a specific meaning within a world city network model. In addition, this relational measurement approach is quite flexible. The global network connectivity measure covers firms in six different service sectors; if the connectivity is measured for banking/finance firms only, then a banking/finance measure of connectivity is produced. The results are shown in the right columns of Table 3 . This illustrates two things. First, while London remains number one, Frankfurt rises appreciably to 7th position (still behind Paris for global-scale connections, even in banking). Second, Frankfurt is more narrowly an international financial centre rather than a more rounded global service centre in comparison to London. It is this interlocking model that informs the main research reported upon: the focus is on global service firms and how they use cities, specifically how they use Frankfurt and London. FRANKFURT AND LONDON IN A EUROPE OF CITIESThe research ran between 2000 and 2001 and was funded by the Anglo-German Foundation for the Study of Industrial Society (Beaverstock et al. 2001). Recent significant developments - the introduction of the new European currency, the Euro, and Frankfurt's new role as home of the European Central Bank and hence capital city of Euroland - were the starting point for our study. An ongoing inventory of relevant information for the period 1998-2001, including UK and German financial press reports, leading trade journal articles and official data, was compiled to provide an overview of knowledge concerning changing Frankfurt-London relations in the public realm. The primary research was a major face-to-face interview survey. In-depth interviews were conducted with key players at the ranks of senior partner, chief executive and so on, in top international producer service firms (as listed in the top ten of their respective business sectors) and institutions in each city. Altogether 48 interviews were conducted with firms in banking, accountancy, law, management consulting and advertising at two census points and 26 interviews were conducted with the senior executives of regulatory, trade and professional organisations and government agencies. A Competition DiscourseAs expected, the discourse dominating the specific topic of concern at the start of the research was premised on competition. Frankfurt was widely regarded as being at a critical point with respect to its development as a world city in rivalry to London. The particular significance of the Euro for Frankfurt's status as a world city was that the new currency, with the UK outside EMU, would give Frankfurt a natural advantage over London in the European region. Firstly, the German government's success, and the UK government's failure, in securing the location of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt as opposed to London, was seen as promoting Frankfurt's position (symbolically at least relative to London), since in future monetary policy for eleven (now twelve) countries would be controlled there. Secondly, the concurrent demise of LIFFE and the success of Deutsche Terminbörse in the international futures market suggested that technological developments were allowing business to slip away from London. Thirdly, with the advent of the Euro, trade and professional reports predicted that Frankfurt would become the city where international banks and other business services (for example accountancy, management consulting, law and advertising) would congregate in future to access an expanding continental European market. Together these changes were expected to significantly raise Frankfurt's profile as a world city in relation to London. As the financial centre of the most powerful economy in Europe (Germany) and the European financial centre for the Eurozone, could Frankfurt emerge from the shadow of London to be the premier world city in Europe? Financial press coverage in Frankfurt and London for the period 1998-2001 depicted a fierce rivalry between the cities. A supposed London versus Frankfurt competition was a top news item with the majority of reports portraying the relationship between the cities as a serious battle for supremacy. In 1998, the year leading up to the new currency, typical commentaries included: "Frankfurt's growth is overshadowed by that of London"; "Frankfurt could reduce the lead of London"; "Will Britain's decision to stay out of the first wave enable Frankfurt to wrest leadership from London?". Frequently the language used to describe Frankfurt-London relations could have been referring to an international war. For example, in the British Financial Times the relationship was described as "a bitter war for supremacy" or "a battle between London and Frankfurt" while the German Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung talked of London as a "threat" and Frankfurt's "powerplay". Frankfurt's Manhattan style office skyline was depicted as a symbol of the city's success and rivalry with the City of London. A series of articles in the Financial Times Deutschland in November 2000 showed a photograph of Frankfurt's skyscrapers and asked "Wie lange stehen diese Türme noch in Frankfurt?" [How long will these towers still be standing in Frankfurt?] . "Was wurde richtig gemacht, was falsch?", "Wie steht die Stadt im internationalen Vergleich da?" [What has been done right, what wrong? What is the position of the city in international comparison?]. This was the way the Frankfurt-London relation was widely portrayed; through primary research on the cities' relationships as service business hubs within a world city network, we set out to look beneath the surface of this powerful media representation. Practitioners Using Frankfurt and LondonThe interviews set out to shed light on the processes underlying relations between London and Frankfurt drawing on the experience of key business practitioners in the two cities. Questioning was designed to draw out, first the firms' adjustment to the Euro with respect to Frankfurt-London relations, and second, perceptions of how each service sector was responding to the Euro with respect to Frankfurt-London in the context of wider global relations. Firms were interviewed on two occasions to evaluate the situation one and two years after the launch of the currency. Where a firm had offices in both cities we investigated the varying importance of, and functions of, offices in both Frankfurt and London. Where a firm had offices in only one city we investigated how it dealt with business in the other city and how this was changing. The results reveal a relationship between the cities that reflects their roles in a global context and is much more complex than simple attribute data comparisons suggest. At an early stage it became clear that it was not possible to single out relations between just two cities confirming our network theoretical framework. Global service provision involves specific operational practices relating to information, skills, labour and cultural flow that transcend but also differentiate the 'space of places'. The Euro as a Trigger of Change?As a starting point for the interviews, we addressed the popular press contention that the introduction of the Euro and the location of the ECB in Frankfurt would change relations between the cities. Responses across sectors in both cities were highly consistent. The overwhelming finding was: first, that business environment and market conditions take precedence over currency in determining relations between the cities; second, that Frankfurt's recent development as a financial and business services centre has not been detrimental to business in London; and, third, that London remains regarded as the unassailable top global city in Europe (Box 1). Box 1 Effects of the Euro - Frankfurt's future as a global city relative to London

Source: Interviews in London and Frankfurt in 2000/2001 Surprisingly, the Euro was a non-issue. The ECB has been an image boost for Frankfurt but has not had a detrimental effect for London as a financial centre. However it was seen as essential that London ensures its inclusion in EU policy-making. Comments showing the lack of importance attached to the Euro as a cause of change include: "The fact that the Euro has not been introduced in England has changed nothing in relation to the leading position of London, including the Euro-business"; "It's having no effect on business strategy"; "There hasn't been a rush to Frankfurt since the introduction of the Euro". These views were strongly reinforced during the telephone interviews of the second census period. No difference of response on the issue of the importance of the Euro on service business relations between London and Frankfurt emerged from a comparison of the two sets of interview results. Recent investigations in both Frankfurt (Spahn et al. 2002) and London (HM Treasury 2003) confirm our findings on the minor role of the new currency as an agent of locational change nearly five years after its introduction. So, if the new currency and Frankfurt's associated new role were not determinants of change, what were? The interviews went on to explore in what ways business and market conditions that were considered so important by interview respondents affect Frankfurt-London relations. A series of cross-cutting tensions and relational networks were found to shape the global and local geography of service business. THE SPACE OF FRANKFURT-LONDON RELATIONS IN A EUROPE OF CITIESMarkets and Tensions - A Global-local SpaceCompetition in globalizing transnational markets was seen as the key driving force behind service network geography. An increasing need to respond to processes of globalization was frequently named as the prerequisite to doing business successfully in the local contexts of London and Frankfurt. In the world of advanced producer service business, relations between the cities can only be meaningfully understood in the context of a 'global-local space' that varies considerably within and between the sectors studied. Banks vary most in the geographical extent of their market operations. Only the largest investment banks claimed to have a truly global business strategy. Most banks were dominant players in a European (or in the case of some UK banks, domestic) market but most indicated that 'international' ambitions are mounting. The regionalization of European financial markets was seen as a key driver of cross-border market participation and local representation. However, business relations between Frankfurt and London consistently reflected London's specialist role as an 'international' hub and Frankfurt's role as a 'local' base for continental European and German business. Continental European banks have no alternative than to run two big operations (a national-based headquarters and a London office) but not all German banks are headquartered in Frankfurt and non-German banks maintain a much smaller presence in Frankfurt than in London - office size is adjusted flexibly to suit market requirements. E-commerce is an increasingly important mode for the development of cross-border ability suggesting that some business flows could bypass Frankfurt. In legal services, increasing global reach was seen as essential to maintain firms' client bases. All major law firms were said to be required to provide an international service. In this context, cross-border relationships between London and Germany have recently mushroomed to enable UK law firms to service transnational clients and access the German market and to enable German law firms to engage with the growing international legal market. Marked national differences in professional practice and business culture have not stood in the way of a spate of mergers. Cross-border relations were seen as essential to business expansion in both countries but whereas Frankfurt is one of several centres for legal services in Germany, albeit by far the most important for corporate legal work, in the UK, international business law practice is confined to London. While accounting and management consulting firms have a tradition of international operations, markets were generally perceived as remaining predominantly local. Yet the expanding European market is creating a shift in business relations. The size of the German market and latent demand for professional services is increasing business relations between London and Frankfurt predominantly for financial services and hi-tech business. National differences in business and professional practice and regulations were emphasised and relations between the cities were seen in terms of a transfer of Anglo-Saxon skills and practice from London to Frankfurt. Advertising products were regarded as crossing borders more easily than those of other services, yet maintaining a local presence remains vital to reflect cultural diversity. One advertising executive commented: "If you took our advertising in the UK or Germany, it's still the same car or it's still the same media, so it's the cultural difference which you have to understand". Although London is the European headquarters for most agencies and widely regarded as a global creative centre of excellence, the success of all service hubs (including Frankfurt and London) was thought to be essential to network competitiveness. However, whereas London clearly is the major advertising centre for the UK market, Frankfurt is one of five main advertising centres in Germany (including Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Munich and Berlin). Relations between London and Frankfurt were found to be fundamentally linked to global and local market conditions. The dynamic nature of customer servicing relationships, labour markets, business products and technologies results in a complexity of contradictory drivers and tensions that firms must continuously manage in order to remain competitive. Specific market characteristics for each sector vary but the basic tension for all firms is reconciling the need for global reach against the need to engage with local markets. This basic underlying tension shapes the Frankfurt-London network space. The Global-local TensionA global-local tension underpins a series of specific tensions relating to organisational structure, knowledge production, operational, and locational issues as illustrated by Figure 1. Demand for cross-border services gives firms the incentive to expand their geographical market coverage and many firms insist that a failure to do so would seriously damage their ability to win business and remain competitive in their market as in the case of London law firms who perceive an absolute need for a physical presence in the German legal market. At the same time, globalizing market competition means that firms also feel considerable pressure to remain physically close to their customers and to engage actively with local markets. These twin pressures lead to an increase in the size of firms to achieve both local and global market coverage and an integrated 'seamless' service across borders. Organisational tension The perceived need for critical mass to compete effectively on a global scale and the stretching of business organisation across geographical space in cross-border markets are associated with contradictory drivers. They lead to organisational consolidation - in legal services, for example, "anything that moves has merged" - and to organisational rationalisation to stay economically competitive. At the same time, firms stress the need to focus on core functions (by outsourcing peripheral functions) and demonstrate flexibility within markets. This produces a counter driver for disaggregation and the de-merging and vertical break up of traditional organisational structures across business services. The pressures for increased industry representation at the top end of the services sectors and at the bottom 'niche' market end are likely to drive continuing restructuring of business relations between London and Frankfurt. Knowledge tension The knowledge products of business services are associated with similar contradictions. Skilled people and their business knowledge are firms' key assets. Competition between firms within labour markets and for market share lead to specialisation but also diversification, so firms can differentiate their services from their competitors. In accountancy, "Everybody's looking now for more and more specialism"; "We're migrating skills [from London] to other European countries, particularly Frankfurt". In legal services, the need to build specialist teams has led to "whole teams being poached" in Frankfurt and London. In management consulting, intense competition for skills is leading to the formation of new business models, strategic alliances and market diversification: "Consulting doesn't describe what we do, nor will describe what we do . we don't naturally fit anyone's segmentation . Frankfurt will be an important part of that and London will". Operational tension At the same time, operational decentralisation and local interpretation is a priority to build customer relationships and engage with local markets. In law, "If you get to number one or two in the UK, you can't pretend to be a global firm if you're offering a number eight operation in Germany, or France, or Italy. You've got to be in the top three everywhere". A German banker in London commented, "You can't just sit here and expect everyone to come . increasingly you have to put your resources onto the ground because you want to be close to the customer . because there's a lot of competition out there". Both de-centralising and centralising tendencies can be seen in operational networks. On the one hand, ICT developments allow functions to be located almost anywhere in the world, yet there are also pressures to control risk and reduce costs by centralising functions. German and continental European banks are increasingly putting key global functions in London: "Centralisation brings control and it's reinforcing the concept of identity and team"; "You have to have a big critical mass in each location to achieve focus on organisational goals . significant hidden non-monetary costs . turn into monetary costs in decentralising . operational risks limit how much division of labour you can have". Locational tension Economic competitiveness also brings a need to disperse functions away from expensive global city locations where possible to reduce space and labour costs. A non-European banker in London told us, "We'll move all our operations out, everything over five years, move them to a cheaper environment . we want to keep the intellectual capital close together at the moment until we can develop the technology that allows to share intellectual learning and capital with each other but do it with technology - that time's probably not very far away". Yet proximity in London and Frankfurt is critical to contemporary service business. The presence of skilled labour markets and the agglomeration economies associated with face-to-face contact and knowledge transfer in global cities are also strong drivers for locational concentration. The same banker went on to tell us "I see more concentration coming in here [London] all the time and less and less in other places . over time you could see a hell of a lot more trading taking place in this environment". Another banker commented, "The need for human contact is incredible, it's still a very, very strong issue . that's an overriding factor. Despite all the potential the internet offers, there will still be a very, very strong desire by management to keep everything co-located". A lawyer noted "Sitting in London I've got both local and global" and an accountant believed "the issues about London and therefore whether face-to-face meeting/conferencing are important, in my view that hasn't changed and will not change." Attempts to resolve these various tensions produce dynamic flows within and between service business networks that play a crucial role in constructing and reconstructing relationships between the cities. But interview discussion highlighted the fact that wider forms of relational networks beyond the discussed office linkages play a key role in shaping London-Frankfurt relations. Interweaving NetworksResponses revealed the complexity of the space of flows associated with cross-border service business operations. We identified four interweaving wider relational networks that affect London-Frankfurt relations (Figure 2). Knowledge networks Flows - 'Local' flows of knowledge between London and Frankfurt are highly interconnected with wider inter-city network flows. Potentially, knowledge can be made available anywhere in the world through a network: "You can do it from almost anywhere and it's only some of the old regulatory structures and things like that that are almost keeping the physical" (Banking, London). "It is out of the network that ideas are being generated ... it doesn't really matter whether this person is in Hamburg or Frankfurt because they take their network with them" (Advertising, Frankfurt). Skills are flowing to Frankfurt - In all sectors, knowledge is being transferred from London to Frankfurt: "You have to . bring the resources to wherever they're needed" and people from London are being sent to Frankfurt to develop the skills of people there, (Accountancy, London). ICT opens up new spatial relationships - ICT is allowing the formation of innovative spatial relations between firms and markets and is an important future medium for firms to engage with local markets globally. Local market knowledge and close client relationships are increasingly important in a competitive market causing firms to feel the need for a physical presence in Frankfurt: "One of the advantages of a network [is] if you have to do something in another country you can adapt it [but] you'll have to have the people there who can smell and feel and know that and who can then realise it" (Advertising, Frankfurt). But technology offers economies of scale "a bifurcation . an execution platform and a research platform that interfaces with customers with little human touch" (Banking, London). These developments open up possibilities of engaging with markets through a smaller local physical presence (see also Grote et al. 2002). Some business flows could bypass Frankfurt - European services headquarters and knowledge concentration remain focused in London. Future business strategies for banking in Frankfurt are likely to be flexible: "There has to be a real business reason . there would have to be a real demand to operate a specific operation out of Frankfurt" (UK Bank); "We kept our service functions there [Frankfurt] on the ground and invested in them" (UK Bank); "We have a presence in Frankfurt to reflect the current role of Frankfurt in the equity markets . our options are open with regard to Frankfurt at the moment but the concentration of investment presently is elsewhere [London]" (Continental European Bank). Scale of presence in Frankfurt is likely to be adjusted to suit market needs. European banks use various familiar front shop brand names to collect business but the handling of those business transactions is done in London for added value, "because that's an efficient place to conduct business" (German Bank) and not all German banks will require a substantial physical presence in Frankfurt. Cultural networks Skilled people flow to London - Location of workforce has become more important than location of customers and where skilled people want to live is a critical labour market and office locational determinant: "Intelligent people who create something new are concentrated in a few special places" (UK Bank, Frankfurt); "We need to be able to recruit good people. As far as our location in London's concerned we can get good people" (Advertising, London); "From the client service point of view, personally, I don't think it's important that we have an office in London at all . but from a point of view of . the team of consultants . for emotional reasons, social reasons, they might not be so keen [to move]" (Management Consulting, London). 'City culture' matters - Skilled workforce are increasingly lifestyle conscious and even key decision-makers have personal (as well as corporate) motivations regarding where they want to work and live. This highlights the importance of the cities as places of consumption: "With modern technology . it doesn't matter whether [markets] are in Frankfurt or in London or even Timbuctoo . people have to live somewhere . you could imagine the relative importance of financial centres being dictated by quite different things from where's the most liquid market, because the liquidity can flow from anywhere - where's the most pleasant to live, theatres, restaurants and all sorts of secondary issues' (Management Consulting, London). Frankfurt lacks 'city buzz' - Ambitious people were said to want to work in London, not Frankfurt. The difficulty of recruiting people in Frankfurt was emphasised in both cities. Attitudes to Frankfurt as a place to live were generally negative. Frankfurt is regarded as "boring" and "dead from seven or eight o'clock at night" (Law, London); "The quality of people I have recruited has become better, but it is arduous. If we can't find people in Germany, we try it internationally but it involves higher costs to get people to move to Frankfurt and there is the language problem" (Law, Frankfurt); "It's extremely difficult to attract German top advertising people to Frankfurt . there is no inspiring environment here" (Advertising, Frankfurt). "The English, Americans or French are not very keen to come to Germany, that's almost non-existent" (Law, Frankfurt). We were told even Germans used to living in London if asked to move to Frankfurt "think it's like being banished to the third world" (Management Consulting, London). Diversity is a strength of London - Diversity of cultures and languages is essential to engage with local markets everywhere from a global city hub and these are available in London. In investment banking, London offices are internationally staffed to incorporate multiple ethnicities in an increasingly "less defined" world: "Part of the supporting infrastructure is . the cosmopolitan nature of London as a city . firms can access any language they need from all the different communities that are actually present in London .. it's about the ease of doing business." Power networks Power flows - More power is concentrated in London than Frankfurt due to the UK's history of global connections. In general, firms' global leadership positions are located in at most eight to ten cities and more key staff are located in London than in Frankfurt with implications for decision-making and global influence. Power relations are constructed by the scale of existing infrastructure and resource investment. A newly elected European leader based in Frankfurt in one international management consulting firm would almost certainly have to move to London "This, rightly or wrongly is where the European leadership sits . if he wanted to change the European location of course he could do that but it's a bit of an effort, there's a little bit of infrastructure!". Frankfurt was described in both cities as a service centre for the local German/European market held back by a lack of skills and excessive regulation. London is an international hub and club - The fact that London is favoured by Americans, particularly US investment banks, was seen as "absolutely critical" to London's position: "The American banks are at the heart of it . they have a lot less attachment to Frankfurt" (Institution, London). English as the international business language, London's openness and merchant heritage are important and lead to a critical mass of skills and knowledge. London was described as "An ever-shifting club . a hub with all of those skills both local and cross-border all around me"; "London is so easy as a global hub - it's a great advantage if you're trying to be a global financial city and you're actually in a global city . there's genuinely global ownership of London" (Non-European Bank). The benefits of openness outweigh the risks - London was seen as providing an infrastructure for transnational business - a producer services 'Wimbledon' - creating scale and critical mass that would not otherwise be present: "Very few companies in the City of London are owned in this country, or capitalised in this country . they're mainly American or European owned now [but] the decisions are still being made here." (Law, London). The volume and strength of business flows was seen as "hard to dislodge" (Institution, London). Frankfurt lacks London's national prominence - Frankfurt's position as one of a number of important German business centres holds back its development relative to London: "Big business is taken away from Frankfurt and is being done elsewhere" . "the decision centre for many things is London and not Frankfurt" (Law, Frankfurt); "[For European banks] this is the village where they meet all their competitors and their financiers" (Institution, London); "I don't think I could point you to a case where anyone has said - ah we can do this in Frankfurt but we can't do it here . I don't remember anyone who has said . what we're going to do is beef up our Frankfurt operations and transfer stuff from London to Frankfurt" (Institution, London). Governance networks Regulation matters - Regulatory context is a critical determinant of cross-border business flows and there are important differences between Frankfurt and London. For London there is a strong emphasis on maintaining balanced regulation and a level playing field while for Frankfurt there is a greater focus on control and internal growth: "The infrastructure of the market is all privately owned in one way or another ... is that a disadvantage or does that just reflect the nature of the market place these days . London will do better . if you're prepared to be open to new competitors . we don't try to bias things in one direction or another". (Institution, London). Frankfurt is less open but this could change - In Frankfurt and London we were told that Germany needs to "open up" and come into line with international business practice to increase its international business activity. European regulatory change and progress towards the single market could force reform within Germany to Frankfurt's advantage as a global city. Enlargement, less regulated labour markets, corporate re-structuring, increasing demand for producer services and the impact of Anglo-Saxon business practice were predicted to increase Germany's power and this could benefit Frankfurt. Harmonisation of accounting standards and growth in European and German equity markets providing a deep liquid pool of capital were said to present an opportunity for Frankfurt's growth. Cross-border governance is an issue for London - Continuing progress towards a single European market was seen as important for London. A level playing field was said to be needed to remove obstacles to fluid cross-border business flows. Ensuring that the UK has equal access to the Single Market if it remains outside EMU and that EU directives are consistently implemented in each member state were key London concerns. City competition is unhelpful to business flows - Institutional conflicts of interest are damaging to cross-border business suggesting a need for co-operation across administrative boundaries. In Germany, conflicting interests arise from the decentralised structure of public and private governance and the separation of Frankfurt as a financial centre from the political capital. In the UK, more focused governance benefits London but institutional conflicts of interest are perceived as holding back London's growth. CONCLUSIONSIn this chapter we have used a major economic event, EMU, to investigate world city network relationships between Frankfurt and London. Such as approach has gone against the grain of almost all previous world city research (e.g. Friedmann, 1986; 1995; Sassen, 1991) and studies of international financial centres (e.g. Lee and Schmidt-Marwede, 1993; Porteous, 1999), which have been deeply embedded in the city-competition discourse spawned from comparative, attributive data analyses. From our perspective, we have couched this study of Frankfurt and London in a relational discourse, which we view as being an imperative project for any meaningful analyses of inter-city change in a society which is characterised by flow, connections, networks and nodes in contemporary globalization. From this relational study of Frankfurt and London at the outset of EMU, with the U.K. and London officially outside of Euroland, we would like to offer three major conclusions. First, and foremost, in spite of the introduction of the Single European currency and the location of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, our research showed that London remains the favoured European global city service business hub. All the evidence suggested that international business flows continue to be focused on London leaving Frankfurt in its shade, which is also evident from the attributive data presented in Tables 1 and 2. The key factors shaping relations between the cities can be pinpointed from the global-local tensions and interweaving networks we have identified:

In short, as with all previous studies of London as an international financial centre (see Taylor et al, 2003), it is the premier European financial city. Second, and in contradiction to the first, we argue that the scale of London's competitive advantage over Frankfurt is not necessarily damaging to Frankfurt in the European space of flows. London does not win at the expense of Frankfurt because they are both integral parts of a European world city network. Our research suggests that London's concentration and proximity of markets, skills and experience in a single location within Europe was seen as a benefit to business in Frankfurt. As these respondents noted: "London has acted as a model for Frankfurt and Frankfurt has profited from looking to London" (Law, Frankfurt); "London is in the space between New York and Europe - it doesn't prevent the Euro area developing" (Institution, London). Skills are flowing to Frankfurt from London. Frankfurt is close to an expanding market and has strong technology and infrastructure - Frankfurt's importance is growing: "Stock market activity in Frankfurt is going to grow compared with London . the UK is a mature market. German GDP is a good deal higher than ours, when German stock market capitalization to GDP is at a comparable ratio to ours, domestic German market activity is going to far exceed ours" . "London will remain the centre for global, cross-border international market activity, Frankfurt will grow hugely in terms of financial services on the back of an expanding German domestic market" (Institution, London). Frankfurt's growing connections with London are seen as essential to the development of international business in Frankfurt and Frankfurt is increasing its importance as a 'gateway city' from London to continental European markets: "London is the European interface and so Frankfurt's strength is good for London" (Institution, London); and "Increasing strength of Frankfurt is feeding into London not draining away from it . greater volume coming out of Frankfurt actually just builds activity in London" (Institution, London); Third, and linked to the second, our research reveals that London-Frankfurt connections are more important than boundaries in the space of inter-city producer service flows. In short, cooperation between firms, institutions and other organizational forms in cities actuants which attend to a world city network (see Beaverstock et al, 2002). Increasing city interdependencies are being brought about by inter-firm competition in cross-border markets supporting the contention that inter-city relations can only be properly understood within the context of a global city network. London's superior strength of global network connectivity does not seem to challenge or be threatened by relations with Frankfurt - so far the growth of both cities has been boosted. Frankfurt has prospered by being within both similar and different webs of connections to London - the cities have different, complementary roles within a Europe of cities. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe would like to acknowledge the Anglo-German Foundation for the Study of Industrial Society for funding this research from the project, Comparing London and Frankfurt as World Cities. REFERENCESBeaverstock. J.V., Doel, M.A., Hubbard, P.J. and Taylor, P.J. (2002) 'Attending to the world: competition, cooperation and connectivity in the world city network', Global Networks, 2 (2), 111-132. Beaverstock, J.V., Hoyler, M., Pain, K. and Taylor, P.J. (2001) Comparing London and Frankfurt as World Cities: A Relational Study of Contemporary Urban Change. London: Anglo-German Foundation for the Study of Industrial Society (http://www.agf.org.uk/pubs/pdfs/1290web.pdf). Beaverstock, J.V., Smith, R.G. and Taylor, P.J. (1999) 'A roster of world cities', Cities, 16 (6), 445-458. Blotevogel, H.H. (2000) 'Gibt es in Deutschland Metropolen? Die Entwicklung des deutschen Städtesystems und das Raumordnungskonzept der "Europäischen Metropolregionen"', in Matejovski, D. (ed) Metropolen: Laboratorien der Moderne. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 179-208. Bördlein, R. (1999) 'Finanzdienstleistungen in Frankfurt am Main. Ein europäisches Finanzzentrum zwischen Kontinuität und Umbruch', Berichte zur deutschen Landeskunde, 73 (1), 67-93. Castells, M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell. 2nd ed. Dicken, P. (1998) Global Shift. London: PCP. 3rd ed. Felsenstein, D., Schamp, E.W. and Shachar, A. (eds) (2002) Emerging Nodes in the Global Economy: Frankfurt and Tel Aviv Compared. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Friedmann, J. (1986) 'The world city hypothesis', Development and Change, 17, 69-83. Friedmann, J. (1995) 'Where we stand: a decade of world city research', in Knox, P.L. and Taylor, P.J. (eds) World Cities in a World System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 21-47. Grote, M.H., Lo, V. and Harrschar-Ehrnborg, S. (2002) 'A value chain approach to financial centres - The case of Frankfurt', Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 93 (4), 412-423. Harrschar-Ehrnborg, S. (2002) Finanzplatzstrukturen in Europa: die Entstehung und Entwicklung von Finanzzentren. Frankfurt am Main: Lang. HM Treasury (2003) The Location of Financial Activity and the Euro. London: HMSO. Holtfrerich, C.-L. (1999) Finanzplatz Frankfurt. Von der mittelalterlichen Messestadt zum europäischen Bankenzentrum. München: Beck. International Financial Services London (2001) International Financial Markets in the UK (April 2001). London: IFSL. Keil, R. and Lieser, P. (1992) 'Frankfurt: global city - local politics', in Smith, M.P. (ed) After Modernism: Global Restructuring and the Changing Boundaries of City Life. New Brunswick, NJ.: Transaction Publishers, 39-69. Keil, R. and Ronneberger, K. (2000) 'The globalization of Frankfurt am Main: core, periphery and social conflict', in Marcuse, P. and van Kempen, R. (eds) Globalizing Cities: A New Spatial Order? Oxford: Blackwell, 228-248. Lee, R. and Schmidt-Marwede, U. (1993) 'Interurban competition? Financial centres and the geography of financial production', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 17 (3), 492-515. Porteous, D. (1999) 'The development of financial centres: location, information externalities and path dependency', in Martin, R. (ed) Money and the Space Economy. Chichester: Wiley, 96-115. Powell, W.W. (1990) 'Neither market nor hierarchy: network forms of organization', Research in Organizational Behavior, 12, 295-336. Schamp, E.W. (1999) 'The system of German financial centres at the crossroads. From national to European scale', in Wever, E. (ed) Cities in Perspective: Economy, Planning and Environment. Assen: Van Gorcum, 83-98. Seifert, W.G., Achleitner, A.K., Mattern, F., Streit, C. and Voth, H.J. (2000) European Capital Markets. Basingstoke: Macmillan. Spahn, P.B., van den Busch, U. et al. (2002) Position und Entwicklungsperspektiven des Finanzplatzes Frankfurt. Wiesbaden: FEH-Report No. 645. Taylor, P.J. (1997) 'Hierarchical tendencies amongst world cities: a global research proposal', Cities, 14 (6), 323-332. Taylor, P.J. (2001) 'Specification of the world city network', Geographical Analysis, 33, 181-194. Taylor, P.J. (2003) World City Network: A Global Urban Analysis. London: Routledge. Taylor, P.J., Beaverstock, J.V., Cook, G., Pain, K. and Pandit, N. (2003) Financial services clustering and its significance for London. The Corporation of London, London. Taylor, P.J. and Catalano, G. (2002) 'World city network formation in a space of flows', in Mayr, A., Meurer, M. and Vogt, J. (eds) Stadt und Region: Dynamik von Lebenswelten. Leipzig: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie, 68-76. Taylor, P.J., Catalano, G. and Walker, D.R.F. (2002) 'Measurement of the world city network', Urban Studies, 39, 2367-2376. Taylor, P.J. and Hoyler, M. (2000) 'The spatial order of European cities under conditions of contemporary globalization', Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 91 (2), 176-189. Table 1: London/Frankfurt attributive data: Key financial market statistics

Sources: i London Stock Exchange (quoted in International Financial Services London (IFSL) 2001). ii Bank for International Settlements (quoted in IFSL 2001). iii Thomson Financial Investor Relations, Target Cities Report 2000 (quoted in IFSL 2001). Table 2: The number of financial institutions in London and Frankfurt

Notes: *as of March 2000 (Source: IFSL 2001). **for 1998 (Source: http://www.hit.de/us/hesloca/financ.htm, accessed 23 May 2001). Source: Seifert et al., 2000. Table 3: Top 20 cities for global network connectivity and banking network connectivity

Source: Taylor and Catalano 2002 Figure 1: Tensions in inter-firm competition

Figure 2: Networks in the global city network

Appendix 1 Global service firms: the GaWC 100

Edited and posted on the web on 11th August 2003

Note: This Research Bulletin has been published in MM Amen, K Archer and MM Bosman (eds) (2006) Relocating Global Cities: From the Center to the Margins Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 23-47 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||