GaWC Research Bulletin 109 |

|

|

|

This Research Bulletin has been published in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31 (2), (2005), 245-268 under the title 'Transnational Elites in the City: British Highly-Skilled Inter-Company Transferees in New York City's Financial District'. doi:10.1080/1369183042000339918 Please refer to the published version when quoting the paper.

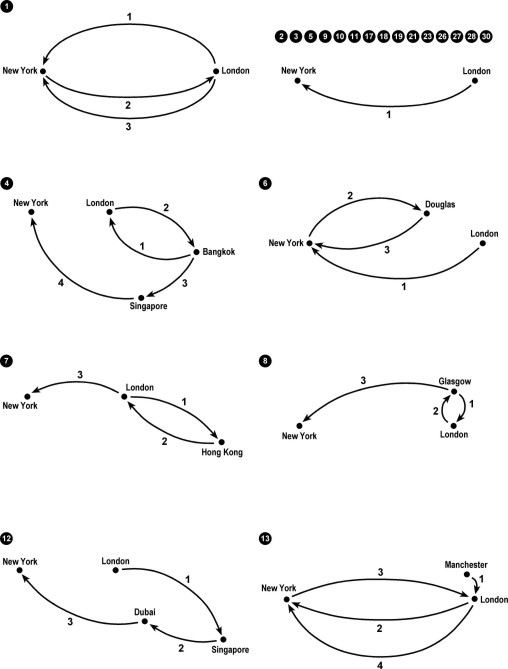

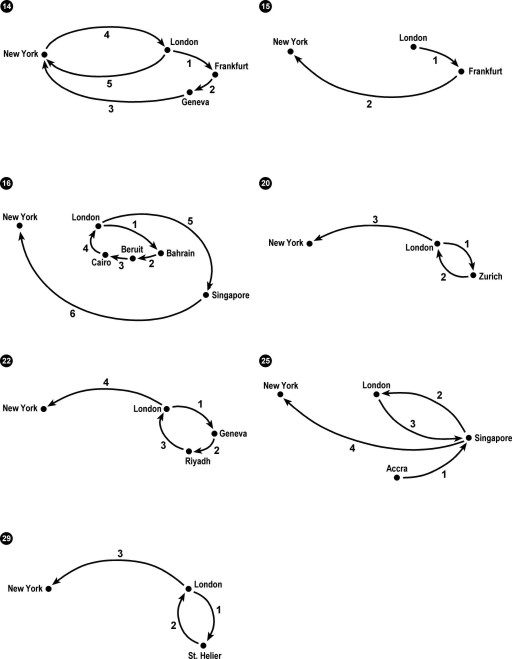

INTRODUCTIONThe circulation of highly-skilled labour between nation-states, often facilitated by inter-company transfers, is creating a new pattern in contemporary international migration systems (Findlay, 1996; King, 2002; Salt, 1997). The changing pattern of highly-skilled international migration from long-term/permanent moves to frequent short-term/non-permanent circulation (Iredale, 2001; Koser and Salt, 1998; Peixoto, 2001), has produced a 'transient' pattern of migration (Appleyard, 1991) and established a highly-mobile, cross-border transnational elite in modern society. As highly-skilled international migrants are becoming more nomadic in scope, they are developing stronger ties and connections in transnational relationships as they compress their time-space flows of organisational practices, knowledge, skills, wealth, social relations and cultural practices between work and home, which often articulated in the (global) city. Transnational elites are vital flows in Manuel Castells's (2000) vision of the Network Society. The development of the Network Society, from a 'space of places' to ' space of flows', is dependent upon flows of capital, information, technology, organisations, symbols, and people, or as Manuel Castells (2000, 445) suggests 'managerial elites', who embody the cross-border circulation of knowledge, skills and intelligence. Ulf Hannerz (1996) and Michael Peter Smith (1999, 2001) recognise that such managerial elites transfer their knowledge cross-border as they enter new urban environments within established cosmopolitan connections and networks, which are reproduced in both work and non-working space. Being a transnational elite is fundamentally associated with being embedded within transnational networks, which are both cross-border (Bailey, 2001; Vertovec, 2002) and also highly-spatialised in the transnational social spaces or translocalities of the city (Smith, 1998; 2001). The corporate migration of highly-skilled professional and managers intra- or inter- transnational service firms is very concentrated between global cities (Beaverstock and Boardwell, 2000). As firms require specialist professionals to be hyper-mobile to deliver intelligence, skills and knowledge at the point of demand, they reproduce a cross-border transnational migrant elite. These knowledge-rich transnational individuals constitute the 'epistemic communities' (Thrift, 1994) that are the crucial mediators and translators of the flows of information, capital and skills that circulate between cities. Saskia Sassen (2001a, 188) refers to these transnational elites as 'the new international professionals' because they 'operate in contexts which are at the same time local and global' and 'are members of a cross-border culture . embedded in a global network of . international financial centres.' In the financial centre, capital is accumulated increasingly by proximity and who you know as well as by what you know (Boden, 1994, 1997; Leyshon and Thrift, 1997). Thus, transnational elites, as well as local elites, are major actors that create financial capital through criss-crossing transnational organisational practices, social relations and discourses, which are articulated in global corporate networks (Amin and Thrift, 1992; Thrift, 1996). The aim of this paper is to investigate the role of British highly-skilled migrants as transnational elites in the knowledge networks of New York's financial district. The rest of this paper is divided into four parts. The following part of the paper presents a discussion of transnational elites in globalisation, which discusses elites as flow in the Network Society, and the spatialisation of transnational networks in the city and financial centre (see Beaverstock, 2002). In the next part of the paper, the interview survey of British highly-skilled migrants is analysed, which investigates their transnational career structures and organisational practices, and working and social networks in New York City. This part of the paper builds significantly upon the research findings of Jonathan Beaverstock (1996). Before the conclusions, the penultimate part of the paper revisits the earlier discussions of highly-skilled migrants as transnational elites in globalisation and suggests that a fundamental characteristic of these migrants elite status are the transnationality of their organisational practices, connections and networks, which were all highly-spatialised in the transnational social space of the global city and financial centre. CONCEPTUALISING TRANSNATIONAL ELITES IN URBAN SOCIETYLike all discourses on transnationalism (Guarnizo and Smith, 1999; Portes, Guarnizo and Landolf, 1999; Smith and Guarnizo, 1998; Vertovec, 1999), a central component of the transnational elite life course is participation in cross-border connections, ties and networks. Transnational elites are highly-mobile, very well connected in economy and society and reproduce their transnational lifestyle with ease through their ability to generate wealth and become embedded into established cosmopolitan global city networks, which criss-cross work, business and the social spheres. In order to refine our explanation of highly-skilled migrants as transnational elites in urban space, three relevant discourses can be discussed: 'managerial' elites as constituents of the Network Society; transnational elites in the city; and, elites as members of transnational corporate networks, which are spatially embedded in the financial centre. Transnational Elites in the Network SocietyThe spatial dynamics of society is based upon a logic of flow, connections, networks and nodes in a space of flows, rather than place-dependency in a space of places (Castells, 1989). A closer examination of Manuel Castells's space of flows suggests that it is constituted not only by electronic exchange and the requirement of the spatialisation of command and control in nodes, but also by the importance of the 'spatial organisation of the dominant managerial elites (rather than classes)' (2000, 443). Manuel Castells (2000, 445) argues that the technocratic-financial-managerial elite occupy leading positions of command and control in the world-system as the 'third important layer of the space of flows'. Moreover, such elites are resident in the spatialities of global cities because these are the nodal points of the Network Society, where they reproduce their cosmopolitan interests, create wealth and reproduce their transnational practice. Thus, for Manuel Castells, managerial elites are 'global' and are themselves part of the flow, and their direction, magnitude and mobility reproduces the space of flows in the strategic nodes. Manuel Castells (2000, 446) talks of elites having 'personal micro-networks' which include 'the residential and leisure-orientated spaces, which along with the location of headquarters, tend to cluster dominant functions in carefully segregated spaces.' The ability of managerial elites to participate in networks is a critical argument in the discourse of the Network Society. Transnational Elites in the CityUlf Hannerz (1996) and Michael Peter Smith's (1999, 2001) research on transnationalism and managerial elites in the city adds considerable weight to the argument that elites are constituents of the space of flows. Referring to a Castellian framework (Castells, 1989), Ulf Hannerz (1996, 128) emphasises the importance of relationships and transnational flow, as he suggests, 'world cities are places in themselves, and also nodes in networks; their cultural organisation involves local as well as transnational relationships.' By drawing upon John Friedmann and Goetz Wolff's (1982, 332) ideas of transnational elites being the 'dominant class in the world city', Ulf Hannerz suggests that transnational managerial elites are central actors in world city production. The key function of the transnational managerial elite is to support the global city's corporate economy. Thus, such labour is highly-educated, highly-skilled and wealthy. Moreover, as many of these elites have hyper-mobile international careers and cosmopolitan cultural distinctiveness, they find it relatively easy to move between global cities with very little personal dislocation as they can 'extend their habitats from the world cities into their other locations' (Hannerz, 1996, 129). Ulf Hannerz presents a powerful argument to support the rationale that skilled international migrants remain 'invisible' (Findlay, 1996) because they can adapt easily to their new habitat and, therefore, states recognise them as being an 'acceptable' (politically, socially and economically) segment of modern migration systems (Raghuran, 2000). Michael Peter Smith's (1999, 2001) investigations into transnationalism in the city emphasises the importance of the agency of transnational migrants, which is deciphered through networks, practices and social relations, grounded in space. He argues that contemporary globalisation and the tensions of the global-local dialectic is articulated in the global city through migration and the agency of transnational migrant networks, which are created and reproduced in transnational social spaces or the 'translocality'. Ludger Pries (2001, 6) is in agreement, and argues that transnational social space is constituted in a global city because 'new forms of international migration and the intensified activities of international companies, amongst others, can thus bring about the establishment of transnational social space.' Transnational elites, therefore, habitat specific transnational social spaces or translocalities in the city. Moreover, the territorialisation of practice is intensely reproduced through cross-border corporate, capital, technological, information and cultural transnational networks, and embedded in the spatial nodes of such circuits, which are the translocalities of the city. Global Corporate Networks in International Finance CentersThe economic epicenter of the global city is the financial centre (Pryke and Lee, 1995; Sassen, 2001b; Taylor, et. al, 2003). As the banking, financial and professional business sectors require real-time intelligence, information and specialist services, the spatial logic is one of speed, proximity, concentration and intensity. But, whilst the spatial logic is speed, the medium of exchange is not only virtual communication, but also 'face-to-face' interaction (Nohria and Eccles, 1992). Face-to-face interaction is a daily process in the financial centre and is a pre-requisite for the creation of trust, confidence, reflexivity and reciprocity, acted out in networks (Sassen, 2001a-b; Storper 1997; Willman et. al., 2001). As the financial centre is a highly globalised node, it is dependent upon specialist service workers to provide knowledge into the network. Financial transnational firms constantly circulate labour, of all nationalities, between financial centres. Such migration is more akin to mobility, as it is frequent and, for many, involves numerous international postings (Beaverstock and Boardwell, 2000). Firms employ a nomadic cadre of highly-skilled migrants because they embody the specialist skills and intelligence of a particular product or client relationship that cannot be traded or franchised cross-border because they have to be consumed at the point of demand and delivered through human interaction. Such delivery occurs through the medium of global corporate networks, which are constantly being sustained by highly-skilled migrants, both foreign and national, which flow through the city's financial centre (Amin and Thrift, 1992; McDowell, 1997; Thrift, 1996). Thus, a major characteristics of transnationalism for the highly-mobile, highly-paid and highly-skilled migrants in the financial world, are their transnational connections, relationships and organisational ties to other financial centres which are deeply embedded in transnational networks in specific 'meeting places' (using the Amin and Thrift's [1992] terminology). BRITISH HIGHLY-SKILLED MIGRANTS IN NEW YORK'S FINANCIAL DISTRICTThirty British highly-skilled migrants were interviewed in New York's financial district in 2000. All interviews were negotiated with London based Human Resources Directors' of transnational financial corporations, and then confirmed and executed on site during the visit. The interview schedule sought data on the migrants': occupations and career paths; business, working and social networks; everyday expatriate experiences; household formation; and, place of residence. All but one interview was taped. Individuals and firms remain anonymous to protect confidentiality. The remainder of this part of the paper is divided into four parts. First the personal characteristics of the migrants are highlighted. Second, the international spatial career paths of the migrants are discussed. Third the organisational roles of the migrants are investigated, which teases out the transnational connections, ties and networks of these individuals, and their everyday working experiences in New York City. Fourth, the transnational networking practices of the migrants are analysed, which emphasises the role of transnational networks in the translocalities of both work and social space. Household Formation, Occupation and GenderPersonal attributes, such as age, marital status, gender, occupation, seniority and where you live, are factors that reproduce the everyday life experiences of the British highly-skilled migrants interviewed in New York. These personal attributes instil particular intellectual, social and cultural capital into elite lifecourses, and also establishes certain creation opportunities, consumption patterns, social relations and cosmopolitanism. From the interview survey, five major observations can be reported concerning the personal characteristics of these individuals (Table 1). First, 83 per cent (25) were men, thus perpetuating the gendered labour markets for inter-company transfers and professional labour in the financial service industry (Kofman, 2000; McDowell, 1997). Second, with respect to household formation, 60 per cent were married, with over half of the group having children (all attending schools in the New York Tri-State area). Moreover, those migrants that were married tended to be in more senior positions within the receiving office and had more experience of working in other financial centres. Most of those migrants who were on assignment for the first time in their career were single. Third, with respect to occupation and grade, almost all of the migrants were senior members of the firm. The majority of migrants were in the thirty to forty age-bracket, and age reflected their seniority within the firm, trans-mobility and marital status. Fourth, linked to occupation, the survey indicated the short-time periods of employment contracts in the New York office (the medium length of stay was 2 years). Fifth, with respect to the place of residence, seven married migrants with children of schooling age lived outside of New York City (in Connecticut and New Jersey) with the remainder living in Manhattan, and especially the Upper East and West Sides, and Midtown. None of the migrants could identify their place of residence as being an 'expatriate enclave', instead, they all stressed that they just 'blended in' (often quoted) to New York apartment life in very global, multi-nationality neighbourhoods. Transnational Mobility: Spatial International Career PathsChanging firms and changing workplaces in cross-border moves between financial centres is an important process by which highly-skilled workers disseminate and accumulate knowledge in the financial centre. For this group of workers, an important constituent of their transnationalism is the business and social related ties and connections that are accumulated from past working experiences. Twelve migrants (40%) had past experiences of working in other financial centres (e.g. Bangkok, Singapore, Bahrain, Beirut, Cairo, Frankfurt, Geneva, Zurich), with either their current or an array of former employers (for the other 18, this posting to New York was their first assignment) (Table 2, Figure 1). Four migrants had been posted to New York City previously (for one year or more) in their transnational career paths.Each migrant had their own transnational story of how their mobility, career development, knowledge accumulation and dissemination was embedded within daily cross-border business connections and ties with other financial centres (in different time-zones). This short vignette illustrates why work and careers are fundamental characteristics of their existence as transnational elites. Respondent Four joined Standard Chartered Bank in Edinburgh and was then sent to Bangkok as a trainee analyst on the Thai equity market. He was in Bangkok for four years where he specialised in the Asian equity market, which resulted in frequent business travel between all east Asian financial centres. In 1994, he was repatriated to London for two years to work on the Asian dealing desk, which involved daily contact with east Asia. In 1996 he was recruited by a French bank and sent back to Bangkok as a broker on the Thai equity market. In 1998 he was sent to Singapore for eighteen months to broker in all the Asian markets and he was sent to New York in 1999 to head the banks Asian desk. In his New York office he regularly works 18 hour days to ensure that he starts the day as the Asian markets are closing and finishes the day as the Asian markets are preparing to open, with a constant real-time dialogue between Paris (H.Q.), London and Singapore. For this migrant, cross-border real-time knowledge and intelligence flows were a daily working-routine, as he suggested, 'I rely on the information flow that I get out of those markets to basically keep my clients up to date with what's happening . you get e-mails and voice-mails here.' Transnational mobility, between firms and other financial centres, and the establishment of international career paths were suggested by all migrants as being the most important factor in their motivation to work outside of London. All migrants indicated that their migration experiences, including their present posting to New York, was highly beneficial to their own career path, with respect to both promotion within the firm and intellectual and social capital accumulated through business interaction with the New York business community. A posting to New York was deemed by all as being the 'prized' location for their career to fast-track, both within the city and on return to London. Wall Street was viewed by all migrants as being the largest financial market where the most influential players, clients and business networks could be penetrated, and invaluable knowledge, experience, contacts sought. As this migrant commented,'I mean just the influence of London is so heavily American influenced that at the end of the day a secondment with them . for you on your C.V. is very good because it shows that the firm trusts you to go abroad to effectively represent them . I mean on secondment the best one is New York . New York's meant to be the capital market centre of the world, it's the best of the best and if you go back to London you go 'I worked in New York' and people will treat you differently'' (10).For the majority of migrants, their preference to be placed on secondment in New York City for career advancement (and for all, also the cultural and social experience of living in city) was matched by their organisation wishing to assign them to the city for business requirements. In almost all cases, the knowledge and experience that the migrants were bringing to their firm's networked environment was much more than the individual parts of their generic skills. As one migrant commented:'If you get someone from an overseas office your getting someone whose already travelled and also knows the ways of the firm and it also brings someone whose got some contacts as well as experience. It helps to push globalisation' (2).It was the sum of their skills, practical knowledge and 'know how', experiences of previous assignments, if applicable, and London business networks, which were maintained constantly by email, fax, telephone and business travel once in New York City. The Organisational Rationale for Postings to New York CityAll the migrants acknowledged that they were selected for their New York assignment because they had the management experience, specific skills and expertise accumulated from working and networking in London or other financial centres, which were in demand by their employer in New York, at that particular moment in time. The most important organisational rationale for a posting to New York City was the migrant's ability to transfer specific skills into the local workplace, whether that be the firm or on secondment to a particular client. In most cases, to coin the phrase of one interviewee, almost all migrants were selected because they were 'bringing intricate knowledge of the U.K. and Europe to the U.S..' Or as one migrant bluntly suggested, 'My bosses here didn't recruit me because of some grand objective of increasing the integration between the U.S. and U.K.. They recruited me because I have got the skills that they can sell and make money out of. I am a short-term economic migrant' (3).In short, all of the migrants were posted to New York City to transfer their specific generic intelligence, knowledge and skills from London or another financial centres, as these two brief commentary illustrates,'The bank was looking to expand its activities in the U.S. by opening new offices. They brought two out at the time with a view to moving into the new office . The whole reason for being here is to do business and to earn money for the bank. You need to have people who understand the market. So you have the benefit of . knowing what happens in the U.K. . [in London] . and the U.S. market' (8).'Jim's the Vice-President of Treasury of London and New York so he's got all the personnel under him. I've got all the experience on the analytical side . [from London] . and he's as I say the accounting side. The way treasury's going is not just a case of do I make money. It's a case of knowing exactly what there is . from the analytical side I'm here . [in New York] . to shake that up' (30).Coupled with the need to be able to transfer knowledge from London into the New York context, all migrants were required to be in daily contact with knowledge networks or clients in London or other financial centers. Equally, all migrants agreed that their 'U.S. clients like having a U.K. person on hand in the same time-zone to answer questions' (21), especially on the London, European or Asian real-time markets. Beyond the organisational rationale of transferring specific skills across national boundaries, several migrants highlighted the significance of trust that they brought to their organisation's New York office, and business network. The idea that only migrants, and not locals, could be trusted to manage banking functions in non-U.S. firms in particular justified their existence in the organisational structure. One migrant (24) who would not be taped suggested that his bank specifically wanted a 'European' and as he'd been with the bank for ten years they believed that he had brought enough trust and relationships from London to become the bank's treasurer in New York. One other migrant expressed similar thoughts on the relevance of trust,'I replaced an American . I was trusted to the extent that I was well known within the group in London and part of the benefit of this was what the Federal Reserve likes to see . somebody who is in touch. I exercise corporate governance, control, managing risk and audit. I am also the public face of X here. I take up a lot of my time talking to the Federal Reserve' (6). Transnational Elites, Transnational Networks and TranslocalitiesThe research showed that the migrants were assigned to New York City to transfer knowledge, expertise and skills into the firm and the financial district. But, it also became clear that there was another series of 'softer' processes required to assimilate that knowledge in the organisation. Being accepted into the new organisational culture came through network interaction with U.S. and non-U.S. work colleagues. All the migrants agreed that knowledge and skills 'picked up on the job . people don't come to you with information . you ask and you get' (20). The degrees to which these migrants embedded their knowledge and skills into their new organisational culture and immediate financial community, was dependent in many ways on their participation in different layers of transnational business-social related networks. Participation in transnational workplace networks All migrants were questioned about the difficulties associated with adjusting to their new organisational culture, and specifically how they gain 'local' knowledge and trust, credibility and the confidence of their new work colleagues in the host office. All thirty migrants stated that they did not receive any 'formal' training to ease the transition into their new organisational environment before they departed from London, or any other financial centre. They were expected to adapt very quickly to their host office. Thus, assimilating knowledge transferred from London into, and accumulating 'local' knowledge from, the New York context, was, as two migrants suggested comes from, ' . networking . you can't underestimate that. You do gain networks, you gain contacts, you gain experience' (10) and 'picking it [business knowledge] up as you go along' (12). In essence, the organisational success of the posting came through an individual's involvement in work-related and business networks, with colleagues and clients, involving both migrants (of all nationalities) and U.S. citizens alike. In the context of intra-firm networks, the transfer and accumulation of knowledge between migrants and U.S. and non-U.S. colleagues occurred daily in the working environment of the firm. The research revealed that one of the most important knowledge networks, encompassing both assimilation and accumulation, was the interchange of information, practice and intelligence, within the migrant's workplace. As this migrant explained,'Its quite interesting the number of people that I've come across over here that I'd already worked with so it's a good sign that the business world is globalising at pace . its . [networking] . all professional I would say you know its more through work. Its imperative that I go back with a basket of contacts internally that will help the leverage business when I get back' (14).This view on network formation and knowledge circulation within the firm, and the wider Wall Street and Midtown area, was not an unrepresentative view of the interviewees as a whole. Outside of the office, this network interaction occurred at lunchtimes only, included U.S. and non-U.S. nationals, and took place at specific 'meeting places', usually the restaurants in close proximity to their place of work (downtown - Wall Street, World Trade Center, Midtown). All migrants regarded 'internal' networking as the most important process for facilitating knowledge transfer and accumulating specific 'local' market, client or firm intelligence. As one migrant commented,'Its all internal networking. I've bridged the gap across the pond. I've brought London to here. What happens with global sites is that people feel so detached if your global management in New York is responsible for six regions - London, Frankfurt, Sydney, Singapore and Asia' (29).Workplace networking with colleagues, especially U.S. nationals, rarely occurred outside of the lunchtime slot. Almost all the migrants complained that New York City didn't have that City of London 'after work public house, wine bar working/socialising' (2) or 'British Friday night out with work colleagues' (9) culture, which was so important for knowledge transfer and interaction. Some migrants were 'trying to develop it because its really important as its good for the team to get together and reflect' (4), but conceded that it was particularly hard to develop as 'they . [US nationals] . don't go out after work . people tend to go out for lunch" (9). In fact, apart from those small group of migrants who were trying to recreate the City of London evening working networks, the remainder confirmed that they had adopted the American working practice of networking over lunch and rarely mixing with others in a work-social or social context outside of the lunchtime networking arena. As this migrant commented, 'I don't stick with expats. I see them . [work colleagues] . from time to time. I get on with them pretty well but I've deliberately avoided spending too much time with them' (2). Participation in transnational business networks With respect to inter-firm and client networks, which often took place in social spaces, most migrants regularly networked with their clientele or circles of friends who were themselves in an associated financial industry. As one migrant pointed out, 'in the financial sector you see the same faces at the same functions frequently be it business or social' (1). Like with intra-firm networks, these networking activities tended to occur at lunchtimes as 'business lunches', but also on weekends in restaurants (but again during the lunchtime slot). These networks were not as well established as their intra-firm relationships, and membership frequently changed depending upon the context/subject of the network and location (e.g. seminar participation; professional body lunch). Because of the fluidity of network membership, many migrants did find it difficult to 'break-into', as one migrant noted, 'external networking is tricky. The lunch . [I will go] .today that will be an opportunity. For that there were 30 to 40 people representing essential actual clients' (2). For two migrants, an important event for inter-firm networking activities was membership of a formalised business association: the United States International Business Council (2) and the British American Chamber of Commerce (21). In both cases, it was corporate membership, and their role was to interact with U.S. business people in network, especially to: tout for business; find out about the market; and any government legislation that is going to be introduced. All of the migrants interviewed noted that networking with clients, potential clients and competitors was just an 'everyday part of the financial community' (12), 'here in the city we tend to be a member of a much tighter network . all tied up, trade related and business contacts' (16). All of the migrants interviewed undertook business related networking activities outside of the formal workplace with U.S. citizens, other British and migrants of other nationalities. It was an essential vector for the success of their transnational existence as elites in the city and financial district. Participation in transnational social networks Little evidence suggested that this group of migrant mingled with other British migrants or U.S. and non-U.S. work colleagues in a purely social context. 'If my social side was related purely to colleagues then it would be a very dull place' (30) exclaimed one migrant. Socially, these migrants enjoyed the company of other British or U.S. friends on weekends and in the holiday season, but these were not work related colleagues. Four points can be made about social networking. First, as all of these migrants worked very long hours from Monday to Friday (because they had to be available to clients and be in real-time contact with London or Asia), weekends were valued as important 'resting' and 'recuperation' time. Second, as over half of these migrants were married with children, time outside of work was focused on the family. Those migrants who resided in Connecticut and New Jersey had developed strong ties with other British people in these locations, which were particularly sustained through children and schooling. Those single and married couples (without children) who resided in Manhattan have very weak social ties with other British nationals in the city (except with those who lived in their same apartment blocks). Third, many of the single and married migrants (with no children) used weekends to travel as widely as possible. In the summer months, popular destinations were Long Island and New England, and in winter, skiing breaks in New England. Fourth, many of the weekend spaces for socialising occurred in an array of different locations around Manhattan: Central Park; the (Irish) bars and restaurants around residential areas (Upper East/West sides, Midtown) and Lower Manhattan (Greenwich Village); museums, galleries and events (e.g. Theatre); and various charity events. Only one migrant interviewed was a member of an 'expatriate club', The Ridegwood International Newcomers Club, which organised dinners and 'discos' for both couples and singles (18). The remainder actually spent most of their everyday lives trying to avoid such formalised social networks because they didn't want to be associated with 'stereotypical' British practices, and there was a definite sense that it would hinder network formation with U.S. and other nationalities. DISCUSSION: TRANSNATIONAL ELITES IN THE CITYFrom this study of British highly-skilled migrants in New York City, the weight of evidence suggests that these individuals have transnational life courses. Their transnationalism and existence as transnational elites are sustained by the frequency of their cross-border connections, ties and relationships, manifested in their: multi-locational career paths and global organisational and working practices; participation in global-local corporate networks; and, translocality of the financial district in Midtown and Lower Manhattan. Transnational Elites and Organisational PracticeFrom the earlier review of Manuel Castells's (2000) thoughts on the 'managerial elite' in the 'space of flows', Ulf Hannerz's (1996) work on the transnational connections of 'transnational managerial elites' in world cities, and Michael Peter Smith's (1999) analysis of the transnational practices and networks of trans-migrants in the city, this group of highly-skilled migrants have all the major traits of transnational elites in modern society. They are all highly-skilled who themselves have crossed borders at regular intervals to work in global city international financial centres as a 'normal' expectation of their organisational career paths. Moreover, the high frequency and short-time scale of their international mobility sustains the global-local corporate networks of firms and the financial district, as they bring new circuits of knowledge, organisational practice, wealth and agency into the city. The research indicated that these migrants displayed very highly-mobile transnational organisational practices, which were extremely important characteristics of their transnational experiences and status as transnational elites in the city. For this group of transnational elites, the everyday experiences of their elite status is deeply embedded in their organisational culture and working community of practice. Transnational NetworkingThis group of transnational elites reproduce their elite status in the financial district of New York City through participation and agency in global-local corporate networks. At work, they were in constant connection with London and other financial centers, where they daily tapped back into their 'home networks' for real-time intelligence and information. Equally, in the New York office, organisational network formation, with U.S. and non-U.S. colleagues was vital for their success in knowledge creation, dissemination and circulation. This is an important finding because it provides important evidence to illustrate that membership of transnational corporate networks in the workplace was a major determinant of the spatialisation of knowledge within the financial district. Moreover, the research indicated that networking per se was such an important aspect of daily working in the financial district for all concerned, at work or over lunch or at specialist functions. Participation in business associations was important for those who were in such organisations. Networking with business peers, where knowledge was accumulated and exchanged, was the major cornerstone of their transnational existence as elites in the city. In contrast, the research suggested that social networks were very weak, not regular and tended not to be composed of other British migrants attempting to reproduce the stereotypical expatriate lifestyle as discussed in Jonathan Beaverstock's (2002) analysis of British workers in Singapore. In short, for this group of transnational elites, their everyday working and elite experiences are deeply embedded in their organisational network connections with, colleagues back in London or other financial centers; U.S. and other nationality office colleagues; and clients and competitors. Transnational GeographiesManuel Castells (2000) associates the nodes (global city) as the basing-points (using Friedmann and Wolff's [1982] terminology) for the 'managerial elite' in the space of flows. Michael Peter Smith (1998, 1999) argues that the 'trans-locality' is the spatiality of the transnational migrant network. Ulf Hannerz (1996) agrees with both, and suggests that the domicile for the 'transnational managerial elite' is the world city. Within these geographies, the research suggests that for this group of transnational elites their networks and transnationalism is played out in a theatre of distinctive territories. The financial district is the transnational space or trans-locality for these transnational elites. The fieldwork emphasised the workplace and related business-social locales (namely in restaurants during lunchtime) as the key spaces for these transnational elites, where they networked with work colleagues, clients and competitors. Households and other locations were definitely not on the map for transnational migrant networks. Indeed, not one migrant interviewed could name a bar or restaurant close to work or home which had the label of being an 'expatriate' space. CONCLUDING REMARKSIn this paper the discussion has explored how British highly-skilled migrants are transnational elites in the city, whose existence are sustained through accumulating capital and knowledge within organisational and business related global-local networks, grounded in the 'meeting places' of the city. Specifically, three major conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, highly-skilled transient migrants are transnational elites. Such elites are a not only a layer of flow in the Network Society, but their wealth, cosmopolitanism and cross-border organisational, social and cultural ties, and connections make significant contributions to their transnationalism and 'elite' status in the city (as discussed by Bailey, 2001; Hannerz, 1996; Smith 1999, 2001; Vertovec, 2002). Indeed, a substantive finding of this research is that it presents an unparalleled study of transnational elites and their transnational networks in the city. Second, as the intrinsic nature of financial service activities are embodied in the knowledge, skills and intelligence of the professional labour force, which is circulated in both virtual real-time 'face-to-face' corporate networks, a central tenet of the transnationalism of these migrants were their cross-border organisational ties, connections and social relations. All of these elites were in daily contact with colleagues in London or other international financial centers. Third, and linked to the first and second, an analysis of the organisational transnational knowledge networks of these elites in New York City provides detailed evidence to support those economic geographers who espouse ideas about the transmission of 'soft' capitalism in economy (Thrift, 1997). These transnational elites are clearly active in corporate knowledge networks, activated principally in intra- and inter-firm contexts, and grounded in business spaces (the firm, restaurants and business associations). But, of course, to explore ideas of transnationalism at the elite level in modern society, more ethnographic research required. This modest study will hopefully act as a catalyst for others to research transnational elites in the city. NOTE* This research was executed before the destruction of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. All the migrants interviewed in this research and their dependents survived the tragic events of that day. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe Economic and Social Council's Transnational Communities Programme for funding this research in the project 'Embeddedness, Knowledge and Networks: British Expatriates in Global Financial Centres' and The British Academy's Overseas Conference Grant Committee (31399). I am also indebted to the research assistantship of Dr Richard Bostock. BIBLIOGRAPHYAmin, A. and Thrift, N. (1992) 'Neo-Marshallian nodes in global networks', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 16 (3): 571-587. Appleyard, R. (1991) International Migration. Challenge for the Nineties. Geneva: IOM.Bailey, A. J. (2001) 'Turning transnational: notes on the theorisation of international migration', International Journal of Population Geography, 7 (3): 413-428. Beaverstock, J. V. (1996) 'Re-visiting high-waged labour market demand in the global cities: British professional and managerial workers in New York City', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 20 (4): 422-445. Beaverstock, J. V. (2002) 'Transnational elites in global cities: British expatriates in Singapore's financial district', Geoforum, 33 (4): 525-538. Beaverstock, J. V. and Boardwell, J. T. (2000) 'Negotiating globalization, transnational corporations and global city financial centres in transient migration studies', Applied Geography, 20 (3): 227-304. Boden, D. (1994) The Business of Talk. Cambridge: Polity Press. Boden, D. (1997) 'Temporal frames. Time and talk in organizations', Time and Society, 6 (1): 1-33. Castells, M. (1989) The Informational City. Oxford: Blackwell.Castells, M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell. Findlay, A. M. (1996) 'Skilled transients: the invisible phenomenon' in Cohen, R. (ed.) Cambridge Survey of World Migration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 515-522. Friedmann, J. and Wolff, G. (1982) 'World city formation: an agenda for research and action', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 3 (3): 309-344. Guarnizo, L. E. and Smith, P. M. (1999) Transnationalism From Below. New Brunswich: Transaction Publishers. Hannerz, U. (1996) Transnational Connections. London: Routledge. Iredale, R. (2001) 'The migration of professionals: Theories and typologies', International Migration, 39 (1): 7-24. King, R. (2002) 'Towards a new map of European migration', International Journal of Population Geography, 8 (1): 89-106. Kofman, E. (2000) 'The invisibility of skilled female migrants in European migratory spaces', International Journal of Population Geography, 6 (1): 45-59. Koser, K. and Salt, J. (1997) 'The geography of highly-skilled international migration', International Journal of Population Geography, 3 (2): 285-303. Leyshon, A. and Thrift, N. J. (1997) Money/Space. London: Routledge. McDowell, L. (1997) Capital Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.Nohria, N. and Eccles, R. (Eds.) (1992) Networks and Organization. Structure, Form and action. Boston M.A.: Harvard Business School Press. Peixoto, J. (2001) 'The international mobility of highly-skilled workers in transnational corporations: The macro and micro factors of the organizational migration of cadres', International Migration Review, 35 (4): 1030-1053. Portes, A., Guarnizo, L. E. and Landolf, P. (1999) 'The study of transnationalism: the pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field', Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22 (2): 217-237.Pries, L. (ed.) (2001) New Transnational Social Spaces. London: Routledge. Pryke, M. and Lee, R. (1995) 'Place your bets: Towards an understanding of globalisation, socio-financial engineering and competition within a financial centre', Urban Studies, 32 (3): 329-344. Raghuran, P. (2000) 'Gendering skilled migratory streams. Implications for conceptualizations of migration', Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 9 (4): 429-457. Salt, J. (1997) International Movements of the Highly-Skilled. International Migration Unit Occasional Paper No. 3. Paris: O.E.C.D.. Sassen, S. (2001a) 'Cracked cases: Notes towards an analytics for studying transnational processes', in Pries, L. (ed.) New Transnational Social Spaces. London: Routledge, 187-207. Sassen, S. (2001b) The Global City. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Smith, P. M. (1998) 'The global city - whose city is it anyway?', Urban Affairs Review, 33 (4): 482-488. Smith, P. M. (1999) 'Transnationalism and the City' in Beauregard, R. and Body-Gendrot, S. (eds.) The Urban Movement. London: Sage, 119- 139. Smith, P. M. (2001) Transnational Urbanism. Routledge, London.Smith, P. M. and L. E. Guarnizo (eds.) (1998) Transnationalism from Below. New Brunswick N.J.: Transaction Publishers. Storper, M. (1997) The Regional World. New York: Guildford Press. Taylor, P. J., Beaverstock, J. V., Cook, G. A. S., Pandit, N. and Pain, K. (2003) Financial Business Clusters in London. London: Corporation of London.Thrift, N. (1994) 'On the social and cultural determinants of international financial centres: the case of the City of London' in Corbridge, S., Martin, R. and Thrift, N. (eds.) Money, Power and Space. Oxford: Blackwell, 327-354. Thrift, N. (1996) Spatial Formations. London: Sage. Thrift, N. (1997) 'The rise of soft capitalism', Cultural Values, 1 (1): 21-57. Vertovec, S. (1999) 'Conceiving and researching transnationalism', Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22 (2): 447-462. Vertovec, S. (2002) Transnational Networks and Skilled Labour Migration. Working Paper Transnational Communities 02-02, Oxford: University of Oxford. Willman, P., Fenton O'Crevy, M., Nicholson, N. and Soane, E. (2001) 'Knowing the risks', Human Relations, 54 (7): 887-931. Table 1: British highly-skilled migrants in New York City: Household formation, occupation and place of residence

Notes **Married to US citizen and Green Card holder *Married to US citizen Source: fieldwork Table 2: International spatial career paths: Location, dates and firms

Source: fieldwork.

Edited and posted on the web on 2nd May 2003 Note: This Research Bulletin has been published in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31 (2), (2005), 245-268 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||